Abstract

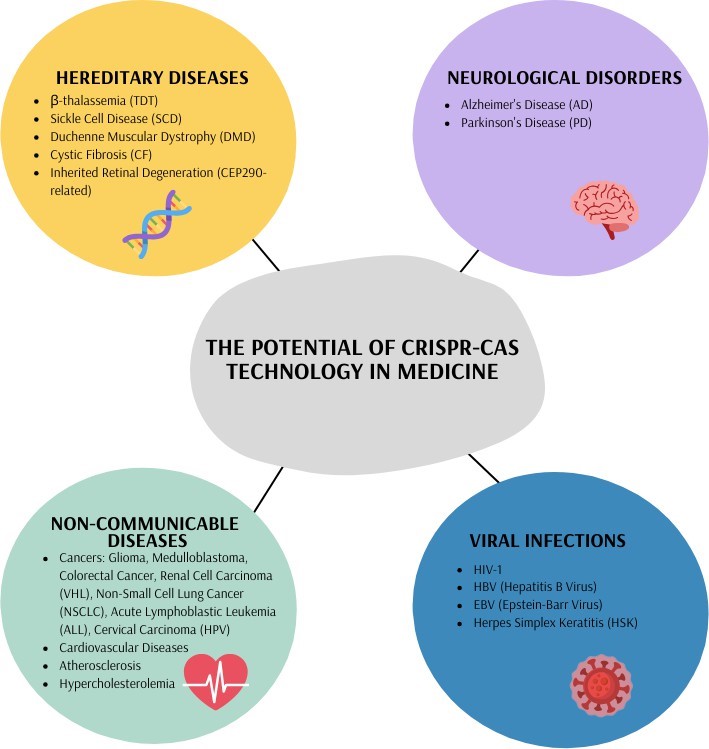

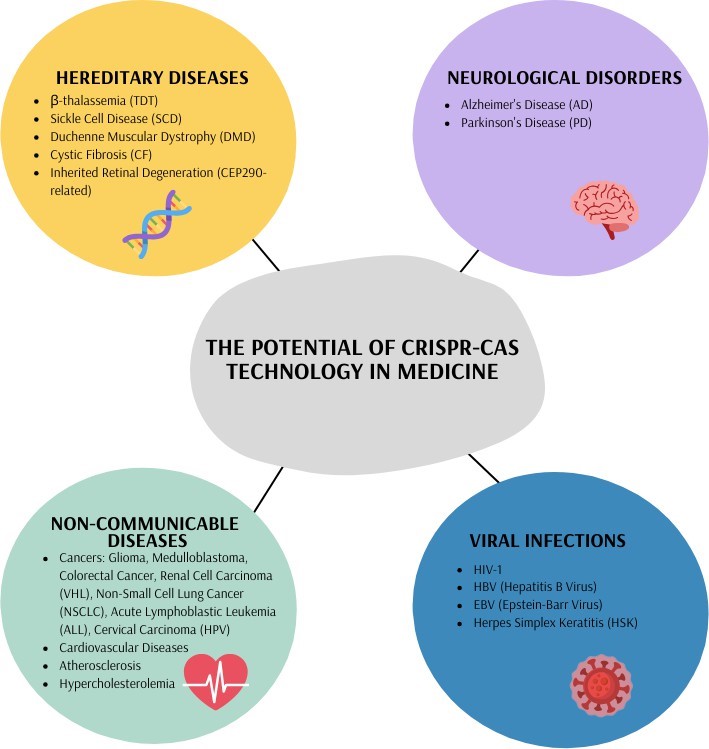

The revolutionary CRISPR-Cas9 system, originating from bacterial defense mechanisms, has swiftly reshaped biomedical research, demonstrating broad applicability in addressing diverse human diseases, including hereditary disorders, non-communicable diseases, neurological illnesses, and viral infections. While the immense potential of CRISPR-Cas9 is evident, critical challenges (e.g. off-targe effects, immune responses, and the ethical considerations of germline editing) persist, underscoring the crucial need for ongoing clinical trials and advancements in delivery methods to ensure its efficacy and long-term safety.

Citation

Murawska A, Modrzyk M, Kufel K M, Czyż D Ł, Braczkowski M. The potential of CRISPR-Cas technology in medicine: a current overview of advancing therapeutics. Eur J Transl Clin Med. 2025;8(2):71-80Introduction

In 1987, Yoshizumi Ishino discovered clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPRs) while searching the E. coli genome. This moment became a landmark in the research of distinct prokaryotic organisms’ genomes, and it contributed to the development of CRISPR-Cas9 technology by Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna. In 2020, the two scientists were awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry [1]. This discovery has revolutionized the field of genome editing and opened the door to novel therapies previously unavailable.

Nowadays, the CRISPR-Cas9 technology is being used in a greater number of therapeutic concepts thanks to our comprehensive knowledge of the human genome. It enables the correction of harmful base mutations or the disruption of disease-causing genes with great precision and efficiency, providing a permanent treatment [2]. The initial ideas were focused on hereditary diseases and based on the concept of correcting mutated genes. However, as time passed and additional research was conducted, the potential targets for its application have extended. Over the past decade, research into CRISPR-Cas9 usage in the treatment of various acquired diseases, including cancers, haemolytic and cardiovascular diseases, immunodeficiency and visual or even neurodegenerative disorders, has expanded significantly, with positive outcomes [3]. This technique has a dramatic impact on the field of gene modification, providing a huge foundation for the development of the research field. However, off-target effects and delivery challenges persist.

There is a long-standing ethical debate about using CRISPR-Cas9 for germline editing due to its ability to modify both germ and somatic cells. These modifications could be passed on to future generations, with unpredictable consequences [4].

In this review, we illustrated the evolution of CRISPR-Cas9 from a fundamental biological tool to clinical use and efficacy in treating various diseases, including hereditary conditions, cancers and viral infections. We outlined specific ways of using CRISPR-Cas9 in exact therapy models and the latest treatment methods.

To provide the latest information on the implementation of CRISPR-Cas9 in biomedical research, we reviewed the most relevant and recent studies. Furthermore, covered the current status of CRISPR clinical trials and delivery methods, as well as the related challenges and opportunities.

Figure 1. The potential of CRISPR-Cas technology in medicine

An overview of CRISPR-Cas systems

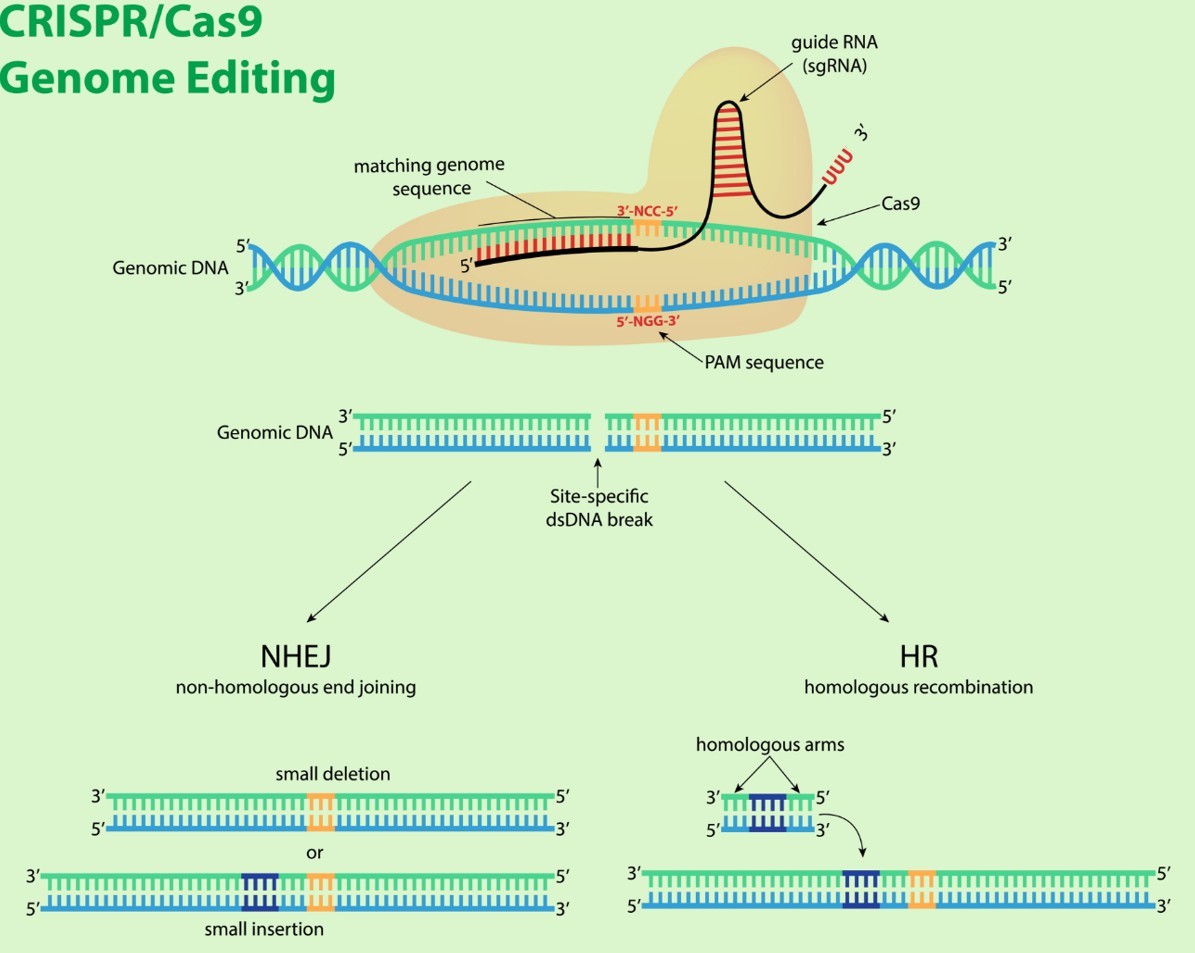

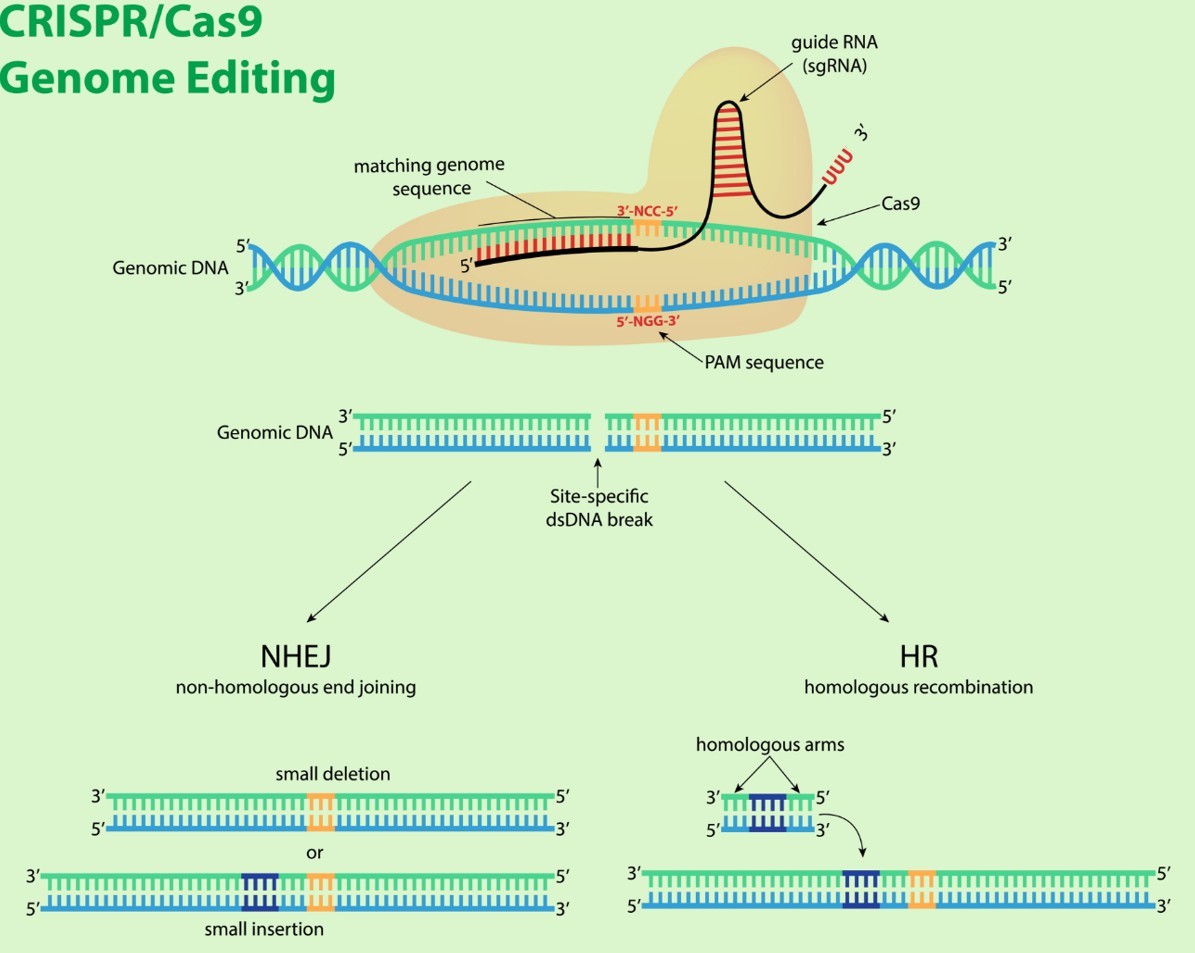

The immune defense of prokaryotes against phage infections, plasmid transfer and foreign substances is determined by the cooperation of CRISPR and an endonuclease called Cas9 protein [5]. Isolated from a prokaryotic cell, the two-component system of single guide RNA (sgRNA) and Cas9, enables a three-step gene modification process in eukaryotic cells: recognition, cleavage and repair. It involves the detection of complementary recipient’s DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) strands and their cleavage, followed by repair of the target sequence by the mechanisms of eukaryotic cells, such as non-homologous end joining or homology-directed repair [6]. The maindelivery strategies for introducing CRISPR-Cas9 systems into cells are physical, viral vector and non-viral vector methods with their distinct advantages and limitations. Electroporation, microinjection and hydrodynamic tail-vein injection are primarily used in vitro studies and are classified as physical methods. Otherwise, in in vivo therapeutic trials, pivotal roles are played by lentivirus (LV) vectors, adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors, and adenovirus (AV) vectors, as well as polymer and lipid nanoparticles or other inorganic carriers categorized as non-viral tools [7]. Gene therapy utilizes two distinct strategies for delivering therapeutic genetic material – in vivo and ex vivo.

They differ from each other in several ways. In vivo therapy does not involve removing, modifying and reintroducing the patient’s cells, which reduces costs. It is mainly used to treat monogenic diseases that affect organs such as the eyes, lungs, liver, and muscles [8-9].

Ex vivo therapy involves extracting cells from a patient, correcting mutations, and then transplanting the modified cells back into the patient. It frequently targets stem cells because the corrected cells can quickly replace those with faulty genes [8]. Additionally, ex vivo modification of T cells for chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell therapies carries a lower risk of disrupting normal gene regulation by insertional events near oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes, which could potentially lead to malignant transformation. This approach can be used for specific cell types that are easy to access, isolate, modify genetically and reintroduce into the patient.

However, the number of cells that can be modified is limited by several factors. These include how efficiently the cells can be collected. They also include how viable and expandable the modified cells are and also include how successful the reinfusion of the engrafted cells is [9].

Fewer off-target effects and enhanced editing outcomes while using CRISPR-Cas9 technology play a superior role among other alternative genome editing tools, such as zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) and TALENs, by providing high efficiency and accuracy [5]. CRISPR gene editing relies on RNA-guided nucleases that introduce double-stranded (DSB) or single-stranded (SSB) breaks in DNA or RNA, and CRISPR genome engineering uses a variety of these nucleases. Each one is distinguished by its target specificity and mechanism of action. For instance, Cas9 generates double-stranded DNA breaks at NGG PAM sites, whereas Cas12 enzymes recognise a protospacer adjacent motif sequence containing mostly thymine bases (T-rich PAMs). They create staggered cuts that facilitate multiplex editing. Cas13 proteins exclusively target single-stranded RNA, enabling precise transcript modulation. The ultra- compact Cas14 family targets single-stranded DNA. This offers advantages for therapeutic delivery where vector size is limited [10-12].

Laboratory examinations indicate that Cas9 can overlook several base-pair mismatches, which could lead to cleavage at off-target sites or slight mismatches in the sequence of the sgRNA [13]. To minimise off-target effects, it is crucial to conduct trials using high-fidelity Cas9 and optimised guide RNA design. Computational algorithms and bioinformatics tools can assist researchers in predicting potential off-target sites [3]. The outcomes of CRISPR-Cas gene editing in humans could be significantly impacted by immune system cascade responses triggered by viral vectors, which could have detrimental consequences for overall wellbeing [3, 14]. Owing to this, pre-existing immune responses to CRISPR effectors and viral vectors (as a form of a cytokine storm) should be considered in personalised treatment strategies. This also applies in terms of exposure to the source bacteria or cross-reactivity with similar epitopes in order to minimise the risk of adverse immune reactions [15]. Another key limitation to the utilisation of CRISPR-Cas9 proteins for genome editing is the requirement that a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) be present at the target site. The Cas9 target site must contain a protospacer PAM sequence to support recognition by this endonuclease. The requirement for a specific PAM sequence reduces the number of possible target sites available for gene knockouts, knock-ins, or highly precise edits, since Cas9 can only operate where an appropriate PAM is present [16-17]. Particularly, it is problematic in disease-related applications, where pathogenic mutations occur at fixed genomic positions that may lack a suitable PAM nearby, making therapeutic editing difficult or even impossible [17]. PAM scarcity also complicates the investigation of regulatory regions and non-coding elements, which often have low PAM density and cannot be easily targeted [18].

BE (Base Editing) is the latest evolution of CRISPR-Cas systems, allowing the direct introduction of point mutations into cellular DNA without the induction of double-strand breaks (DSBs). Two classes of DNA base editors have been identified: cytosine base editors (CBE) and adenine base editors (ABE). The gene editing toolkit has recently been expanded by prime editing (PE), which allows the introduction of all twelve possible transition and transversion mutations, as well as small insertions or deletions [19].

Material and methods

We searched through PubMed and ScienceDirect databases for clinical trials published between January 2015 and March 2025, which focused on CRISPR-Cas9 applications in medicine. Keywords used in the search included “CRISPR-Cas9 in medicine”, “genetic disorders and CRISPR-Cas9 technology”, “non-communicable diseases and CRISPR-Cas9 method implementation”, “CRISPR-Cas9 applications in neurology”, and “genome modification by CRISPR-Cas9 in viral infections”. Studies not written in English were excluded, and the references of included studies were screened for additional relevant publications.

Figure 2. Schematic diagram of CRISPR-Cas9 complex

(Source: AI Generation - Gemini 2.5 Flash Model, 2025)

Results and discussion

Hereditary diseases

CRISPR-Cas tools are widely used in correcting genetic mutations for the treatment of hereditary monogenic disorders such as transfusion-dependent thalassemia (TDT) and sickle cell disease (SCD) [20]. Both are caused by mutations in the haemoglobin subunit gene (HBB). CRISPR-Cas9 technology allows the reduction of BCL11A expression, a key regulator of 𝛽-globin locus expression, by targeting the erythroid-specific enhancer region of BCL11A in haematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs). By restoring γ-globin synthesis and enhancing fetal haemoglobin production, morbidity and mortality measures in patients with TDT and SCD improve [21].

The primary clinical trial for 𝛽-thalassaemia, CLIMBTHAL-111, was analysed in the 2024 interim analysis. The study showed that 91% of the 52 TDT patients achieved transfusion independence following the infusion of CD34+ HSPCs that had been edited using CRISPR-Cas9. Haemoglobin levels stabilised at a mean of 13.1 g/dL total haemoglobin (Hb) and 11.9 g/dL fetal haemoglobin (HbF), with a pancellular distribution of ≥ 94% of red blood cells. No deaths or cancers were reported [22].

The normal structure of the retina, kidney, brain, and a wide range of other bodily organs is dependent on primary cilium formation, which is based on the expression of the gene encoding centrosomal protein 290 (CEP290). Inherited retinal degeneration associated with CEP290 (historically known as Leber congenital amaurosis) is a common cause of visual impairment in the first decade of life. This results from the progressive disorganisation of the outer segments of the rod and cone photoreceptors, as well as the early loss of rod cells in the mid-peripheral retina. In vivo CRISPR-Cas9 therapy involves the permanent removal of the CEP290 IVS26 variant using an AAV vector containing the Staphylococcus aureus (SaCas9) nuclease under the photoreceptor-specific GRK1 promoter [23].

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a fatal X-linked recessive disease that is induced by DMD gene mutations, causing muscle fiber damage during contractions [24]. The significant length of the DMD gene has led to the identification of over 7000 mutations associated with DMD. These often trigger frameshifts and premature stop codons, which subsequently result in dystrophin deficiency [25]. CRISPR-mediated gene editing targets either exon 23 or the mutational hotspot in the DMD gene, causing the removal of the nonsense mutation. The major functional improvements, such as increased contractile force and the restoration of the dystrophin protein, are significant, bearing in mind that complete gene correction was not required [26].

Genetic lesions located on human chromosome 7 (7q31.2) form the basis of cystic fibrosis (CF), a systemic disease that affects multiple organs. The disruption of the crucial cAMP-activated anion channel and CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein production can be caused by over 2000 mutations. These contribute to clinical manifestations that vary in severity, presenting a considerable challenge in the development of targeted treatments [27]. Correction of the F508 mutation by the CRISPR-based gene approach results in the restoration of CFTR channel function [28]. Other studies show that CFTR gene mutations in induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) are achievable via CRISPR-Cas9 technology [29].

Non-communicable diseases

CRISPR-Cas9 technology has become established in cancer research, with applications including: oncogene inactivation, immune checkpoint modulation; genetic mutation correction; and targeted delivery of cancer-killing payloads. The combination of this technique with viability assays and molecular analyses is a valuable approach for identifying drug targets. CRISPR-Cas9 reveals the molecular processes of cancer cells as a result of gene alteration disruption. This enables the selective elimination of cancer cells while sparing healthy ones [30]. The recognition of neoplastic cells and their elimination capabilities by the immune system can be improved in adoptive cell transfer therapies through CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genomic manipulations. Upregulation of gene expression that encodes strategic checkpoint proteins boosts the activation and proliferation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes and other effectors, subsequently improving their ability to eliminate cancer cells [31]. The advantages of CRISPR may help address key challenges associated with chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR-T) cell therapy.

In CAR-T therapy, a patient’s (or donor’s) T lymphocytes express a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR). It recognises a specific antigen on the patient’s cancer cells. Co-delivery of the Cas9-sgRNA complex into primary T cells can either knock out endogenous genes (e.g. TCR and certain inhibitors) or introduce a CAR gene [32]. The use of CRISPR-Cas9 allows the insertion of the CAR gene at a defined genomic locus in a donor’s lymphocyte’s DNA template. template (‘knock-in’ strategy). On the other hand, the ‘knock-out strategy’ disrupts endogenous genes that may limit T-cell performance, cause immune rejection (in the case of donor cells) or reduce persistence. That way, when T cells are reinfused into the patient, they can target and kill cells that express the relevant antigen (e.g. B-cell malignancies) [33].

According to a systematic review and meta-analysis of preclinical studies (i.e. on animal models), CRISPR-Cas9 enhances the therapeutic effect of CAR-T cells. This is achieved through a significant reduction in tumor volume and an improvement in overall survival in almost every model. These findings were consistent across multiple tumor types and multiple CRISPR targets [34]. CRISPR-Cas9 is used to create allogeneic ‘universal’ CAR-T cells by knocking out the endogenous T-cell receptor (TCR) and/ or eliminating HLA Class I expression, which reduces the risk of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and host rejection [35].

CRISPR-Cas9 technology can specifically target genes in non-small-cell lung cancer or, combined with CAR-T, is a promising treatment for relapsed/refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia [36-37] High-fidelity gene editing, manageable toxicity and an 83.3% complete-remission rate were shown by CRISPR-Cas9-engineered universal CD19/CD22 CAR-T cells (CTA101) in a first-in-human phase I trial for r/r ALL. These results demonstrate that dual-target CRISPR-CAR T-cell therapy is clinically feasible and could eliminate the delays and antigen-escape relapse associated with autologous single-target CAR T-cell therapy [37].

CRISPR-Cas9 has the potential to become a cure for medulloblastoma and glioma, due to targeting genes like Ptch1, Nf1, Pten, and Trp53. There is also ongoing research for orthotopic organoid transplantation to repair Trp53 and APC - tumor suppressor genes in epithelial cells, or the Von Hippel Lindau (VHL) gene in renal cells. This could be meaningful for treating colorectal cancer and renal cell carcinoma [38]. Targeting and disrupting specific viral genes within the human genome, such as the E6 or E7 of human papillomavirus (HPV), offers the advantage of suppressing oncogenesis, which can prevent cervical carcinoma [38-39] Compiling the data, CRISPR-Cas9 can be used as an alternative to epigenetic drugs, causing less delivery problems and minimalizing adverse effects [40]. The emergence of CRISPR genome editing has started a new age of research on treating cardiovascular diseases. It has been a useful tool in generating cell lines and mouse models to study genetic cardiomyopathies caused by site-specific mutations, such as long-QT syndrome, Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), Barth syndrome, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) [41-42]. Lowering blood lipids in hypercholesteroloaemia, by using CRISPR-Cas9 can be achieved in following ways: reducing the activity of the lipoprotein and endothelial lipase inhibitor angiopoietin-like 3 (ANGPTL3) or targeting hepato-cyte-derived apolipoprotein C3 (APOC3) [43]. Through the application of the CRISPR-Cas9 system, numerous studies have established disease models of atherosclerosis and revealed potential molecular targets relevant to its pathogenesis. In a Phase 1, first-in-human trial, CTX310 (CRISPR-Cas9 targeting ANGPTL3) was found to significantly lower LDL cholesterol (by approximately 50%) and triglycerides (around 55%) in 15 individuals with severe or refractory lipid disorders such as familial hypercholesterolemia, mixed dyslipidaemia, or severe hypertriglyceridaemia. Phase 2 (or larger-scale) trials have not yet been published. The long-term safety and effectiveness of the treatment, and its impact on atherosclerotic outcomes such as plaque regression and cardiovascular events, are still unknown [44].

Neurological disorders

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder caused by the accumulation of beta-amyloid plaques in the extracellular space and the formation of intracellular neurofibrillary tangles composed of tau proteins [45]. There are two types of AD: sporadic and familial. The familial form is rare, but there is strong evidence which gene variants can disturb the 𝛽-amyloid (A𝛽) metabolism. Mutations arise in: APP (Amyloid-precursor protein), presenilin-1 (PSEN1), and presenilin-2 (PSEN2). Studies reported that using CRISPR-Cas9 technology the expression of A𝛽 protein decreases when pathological APP alleles are deleted, and they also identified possible protective deletion mutations in the 3’-UTR of the APP gene, leading to a massive reduction of A𝛽 accumulation when part of the gene was removed. PSEN1 and PSEN2 are essential components in the regulation of γ-secretase, an enzyme responsible for modulating A𝛽 levels. These specific genes are additional targets for the CRISPR- Cas9 system [46]. Contrary to intuition, the sporadic form of AD also has genetic factors, such as the Apolipoprotein E gene variant APOE4, which can promote neuroinflammatory processes [47]. Recent studies showed that using the CRISPR-Cas9 method to correct the APOE4 allele to E3, it is possible to reduce neuronal susceptibility to ionomycin-induced cytotoxicity, decrease tau phosphorylation, and affect A𝛽 metabolism [46]. Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a health condition characterized by the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra in the area of the basal ganglia. Research has identified several genetic factors that contribute to PD susceptibility, notably mutations in the alpha-synuclein (SNCA), where the mutation results in an abnormal α-synuclein protein that aggregates and accumulates due to impaired proteostasis (UPS – Ubiquitin proteasome pathway and ALP – Autphagy-lysosomal pathway) and PINK1 (PTEN-induced putative kinase), PRKN (Parkin RBR E3 Ubiquitin Protein Ligase), DJ-1 (Daisuke-Junko-1), LRRK2 (Leucine rich repeat kinase 2), and PGC-1α (Pparg coactivator 1 alpha) mutations, which contribute to mitochondrial dysfunction, triggering of neuroinflammatory pathways. These listed genes are also targets for CRISPR-based therapies [48-49].

Viral infections

CRISPR-Cas9 editing offers a potential strategy to target and inactivate integrated viral genomes, particularly in the context of HIV infection [50]. Evidence shows that CRISPR-Cas9 is capable of inducing mutations or excisions in the proviral genome in cells that were latently infected [51]. CRISPR-based HIV-1 strategies include removing the Δ32 to CCR5 (Chemokine C-C motif Receptor 5) mutation in haematopoietic stem cells (HSPCs) and T cells, rendering them resistant to HIV-1 infection [52]. It is also possible to use the CRISPR-Cas9 to modulate HBV’s cccDNA and inactivate the expression of HBV core antigen (HBcAg). Moreover, CRISPR-Cas9 can be applied to suppress EBV’s LMP1, the viral gene that is present in nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) cell lines. By using this method, the tumor growth was inhibited [53]. As results have shown, CRISPR-Cas9/gRNA technology can be seen as a potential treatment for herpes simplex keratitis (HSK). Using vectors, CRISPR-Cas9/gRNA allows to stop the viral replication, destroying HSV reservoirs inside the trigeminal ganglion neurons [54].

Table 1. Summary of key studies

Conclusion

The biomedical research has been revolutionized by CRISPR-Cas9 technology, which has significantly transformed our perspective even on inherited, previously incurable disorders. Novel treatments for various diseases, including hereditary, cardiovascular and neurological conditions, as well as certain tumors, particularly those associated with viral infections, are reachable by precise and efficient manipulation of the human genome using this technique. The recurring issue of adverse effects highlights the need for further research into high-fidelity Cas9 variants and the optimized guide RNAs. Nevertheless, the ongoing discussion surrounding the ethics of germline manipulation has yet to yield any definitive conclusions.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding

None.

References

| 1. |

Gostimskaya I. CRISPR–Cas9: A History of Its Discovery and Ethical Considerations of Its Use in Genome Editing. Biochem [Internet]. 2022;87(8):777–88. Available from: https://link.springer.com/10.1134/S0006297922080090.

|

| 2. |

Huang J, Zhou Y, Li J, Lu A, Liang C. CRISPR/Cas systems: Delivery and application in gene therapy. Front Bioeng Biotechnol [Internet]. 2022;10:942325. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36483767.

|

| 3. |

Aljabali AAA, El-Tanani M, Tambuwala MM. Principles of CRISPR-Cas9 technology: Advancements in genome editing and emerging trends in drug delivery. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol [Internet]. 2024;92:105338. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1773224724000066.

|

| 4. |

Alsmani S. Ethical issues concerned with CRISPR-cas9 system. 2023.

|

| 5. |

Li T, Yang Y, Qi H, Cui W, Zhang L, Fu X, et al. CRISPR/Cas9 therapeutics: progress and prospects. Signal Transduct Target Ther [Internet]. 2023;8(1):36. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41392-023-01309-7.

|

| 6. |

Asmamaw M, Zawdie B. Mechanism and Applications of CRISPR/Cas-9-Mediated Genome Editing. Biologics [Internet]. 2021;15:353–61. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34456559.

|

| 7. |

Du Y, Liu Y, Hu J, Peng X, Liu Z. CRISPR/Cas9 systems: Delivery technologies and biomedical applications. Asian J Pharm Sci [Internet]. 2023;18(6):100854. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1818087623000818.

|

| 8. |

Volodina O, Smirnikhina S. The Future of Gene Therapy: A Review of In Vivo and Ex Vivo Delivery Methods for Genome Editing-Based Therapies. Mol Biotechnol [Internet]. 2025;67(2):425–37. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38363528.

|

| 9. |

Gostimskaya I. CRISPR-Cas9: A History of Its Discovery and Ethical Considerations of Its Use in Genome Editing. Biochemistry (Mosc) [Internet]. 2022;87(8):777–88. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36171658.

|

| 10. |

Hillary VE, Ceasar SA. A Review on the Mechanism and Applications of CRISPR/Cas9/Cas12/Cas13/Cas14 Proteins Utilized for Genome Engineering. Mol Biotechnol [Internet]. 2023;65(3):311–25. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36163606.

|

| 11. |

Kleinstiver BP, Sousa AA, Walton RT, Tak YE, Hsu JY, Clement K, et al. Engineered CRISPR-Cas12a variants with increased activities and improved targeting ranges for gene, epigenetic and base editing. Nat Biotechnol [Internet]. 2019;37(3):276–82. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30742127.

|

| 12. |

Swarts DC, Jinek M. Mechanistic Insights into the cis- and trans-Acting DNase Activities of Cas12a. Mol Cell [Internet]. 2019;73(3):589-600.e4. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30639240.

|

| 13. |

Chen Q, Chuai G, Zhang H, Tang J, Duan L, Guan H, et al. Genome-wide CRISPR off-target prediction and optimization using RNA-DNA interaction fingerprints. Nat Commun [Internet]. 2023;14(1):7521. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-023-42695-4.

|

| 14. |

Roy S. Immune responses to CRISPR-Cas protein. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci [Internet]. 2021;178:213–29. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33685598.

|

| 15. |

Ewaisha R, Anderson KS. Immunogenicity of CRISPR therapeutics—Critical considerations for clinical translation. Front Bioeng Biotechnol [Internet]. 2023;11. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fbioe.2023.1138596/full.

|

| 16. |

Kleinstiver BP, Prew MS, Tsai SQ, Topkar V V., Nguyen NT, Zheng Z, et al. Engineered CRISPR-Cas9 nucleases with altered PAM specificities. Nature [Internet]. 2015;523(7561):481–5. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/nature14592.

|

| 17. |

Yang Y, Xu C, Shen Z, Yan C. Crop Quality Improvement Through Genome Editing Strategy. Front genome Ed [Internet]. 2021;3:819687. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35174353.

|

| 18. |

Karimi MA, Paryan M, Behrouzian Fard G, Sadeghian H, Zarrinfar H, Hosseini Bafghi M. Challenges and Opportunities in the Application of CRISPR-Cas9: A Review on Genomic Editing and Therapeutic Potentials. Med Princ Pract [Internet]. 2025;1–17. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/40675140.

|

| 19. |

Kantor A, McClements ME, MacLaren RE. CRISPR-Cas9 DNA Base-Editing and Prime-Editing. Int J Mol Sci [Internet]. 2020;21(17). Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32872311.

|

| 20. |

Liu W, Li L, Jiang J, Wu M, Lin P. Applications and challenges of CRISPR-Cas gene-editing to disease treatment in clinics. Precis Clin Med [Internet]. 2021;4(3):179–91. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34541453.

|

| 21. |

Frangoul H, Altshuler D, Cappellini MD, Chen Y-S, Domm J, Eustace BK, et al. CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing for Sickle Cell Disease and β-Thalassemia. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2021;384(3):252–60. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33283989.

|

| 22. |

Locatelli F, Lang P, Wall D, Meisel R, Corbacioglu S, Li AM, et al. Exagamglogene Autotemcel for Transfusion-Dependent β-Thalassemia. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2024;390(18):1663–76. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38657265.

|

| 23. |

Pierce EA, Aleman TS, Jayasundera KT, Ashimatey BS, Kim K, Rashid A, et al. Gene Editing for CEP290-Associated Retinal Degeneration. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2024;390(21):1972–84. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38709228.

|

| 24. |

Happi Mbakam C, Lamothe G, Tremblay G, Tremblay JP. CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Therapy for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Neurotherapeutics [Internet]. 2022;19(3):931–41. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35165856.

|

| 25. |

Chemello F, Olson EN, Bassel-Duby R. CRISPR-Editing Therapy for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Hum Gene Ther [Internet]. 2023;34(9–10):379–87. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37060194.

|

| 26. |

Erkut E, Yokota T. CRISPR Therapeutics for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Int J Mol Sci [Internet]. 2022;23(3):1832. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/23/3/1832.

|

| 27. |

Wang G. Genome Editing for Cystic Fibrosis. Cells [Internet]. 2023;12(12):1555. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4409/12/12/1555.

|

| 28. |

Maule G, Arosio D, Cereseto A. Gene Therapy for Cystic Fibrosis: Progress and Challenges of Genome Editing. Int J Mol Sci [Internet]. 2020;21(11):3903. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/21/11/3903.

|

| 29. |

Da Silva Sanchez A, Paunovska K, Cristian A, Dahlman JE. Treating Cystic Fibrosis with mRNA and CRISPR. Hum Gene Ther [Internet]. 2020;31(17–18):940–55. Available from: https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/hum.2020.137.

|

| 30. |

Chehelgerdi M, Chehelgerdi M, Khorramian-Ghahfarokhi M, Shafieizadeh M, Mahmoudi E, Eskandari F, et al. Comprehensive review of CRISPR-based gene editing: mechanisms, challenges, and applications in cancer therapy. Mol Cancer [Internet]. 2024;23(1):9. Available from: https://molecular-cancer.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12943-023-01925-5.

|

| 31. |

Vimal S, Madar IH, Thirumani L, Thangavelu L, Sivalingam AM. CRISPR/Cas9: Role of genome editing in cancer immunotherapy. Oral Oncol Reports [Internet]. 2024;10:100251. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2772906024000979.

|

| 32. |

Dimitri A, Herbst F, Fraietta JA. Engineering the next-generation of CAR T-cells with CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing. Mol Cancer [Internet]. 2022;21(1):78. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35303871.

|

| 33. |

Song P, Zhang Q, Xu Z, Shi Y, Jing R, Luo D. CRISPR/Cas-based CAR-T cells: production and application. Biomark Res [Internet]. 2024;12(1):54. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38816881.

|

| 34. |

Maganti HB, Kirkham AM, Bailey AJM, Shorr R, Kekre N, Pineault N, et al. Use of CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing to improve chimeric antigen-receptor T cell therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of preclinical studies. Cytotherapy [Internet]. 2022;24(4):405–12. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35039239.

|

| 35. |

Razeghian E, Nasution MKM, Rahman HS, Gardanova ZR, Abdelbasset WK, Aravindhan S, et al. A deep insight into CRISPR/Cas9 application in CAR-T cell-based tumor immunotherapies. Stem Cell Res Ther [Internet]. 2021;12(1):428. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34321099.

|

| 36. |

Jiang C, Lin X, Zhao Z. Applications of CRISPR/Cas9 Technology in the Treatment of Lung Cancer. Trends Mol Med [Internet]. 2019;25(11):1039–49. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31422862.

|

| 37. |

Hu Y, Zhou Y, Zhang M, Ge W, Li Y, Yang L, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-Engineered Universal CD19/CD22 Dual-Targeted CAR-T Cell Therapy for Relapsed/Refractory B-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Clin Cancer Res [Internet]. 2021;27(10):2764–72. Available from: https://aacrjournals.org/clincancerres/article/27/10/2764/665638/CRISPR-Cas9-Engineered-Universal-CD19-CD22-Dual.

|

| 38. |

Rabaan AA, AlSaihati H, Bukhamsin R, Bakhrebah MA, Nassar MS, Alsaleh AA, et al. Application of CRISPR/Cas9 Technology in Cancer Treatment: A Future Direction. Curr Oncol [Internet]. 2023;30(2):1954–76. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36826113.

|

| 39. |

Solanki D, Murjani K, Singh V. CRISPR-Cas based genome editing for eradication of human viruses. In 2024. p. 43–58. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1877117324001613.

|

| 40. |

Ansari I, Chaturvedi A, Chitkara D, Singh S. CRISPR/Cas mediated epigenome editing for cancer therapy. Semin Cancer Biol [Internet]. 2022;83:570–83. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33421620.

|

| 41. |

Kyriakopoulou E, Monnikhof T, van Rooij E. Gene editing innovations and their applications in cardiomyopathy research. Dis Model Mech [Internet]. 2023;16(5). Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37222281.

|

| 42. |

Saeed S, Khan SU, Khan WU, Abdel-Maksoud MA, Mubarak AS, Aufy M, et al. Genome Editing Technology: A New Frontier for the Treatment and Prevention of Cardiovascular Diseases. Curr Probl Cardiol [Internet]. 2023;48(7):101692. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0146280623001093.

|

| 43. |

Hoekstra M, Van Eck M. Gene Editing for the Treatment of Hypercholesterolemia. Curr Atheroscler Rep [Internet]. 2024;26(5):139–46. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38498115.

|

| 44. |

Laffin LJ, Nicholls SJ, Scott RS, Clifton PM, Baker J, Sarraju A, et al. Phase 1 Trial of CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing Targeting ANGPTL3. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2025;393(21):2119–30. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/41211945.

|

| 45. |

Bhardwaj S, Kesari KK, Rachamalla M, Mani S, Ashraf GM, Jha SK, et al. CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing: New hope for Alzheimer’s disease therapeutics. J Adv Res [Internet]. 2022;40:207–21. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2090123221001351.

|

| 46. |

De Plano LM, Calabrese G, Conoci S, Guglielmino SPP, Oddo S, Caccamo A. Applications of CRISPR-Cas9 in Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders. Int J Mol Sci [Internet]. 2022;23(15). Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35955847.

|

| 47. |

Hanafy AS, Schoch S, Lamprecht A. CRISPR/Cas9 Delivery Potentials in Alzheimer’s Disease Management: A Mini Review. Pharmaceutics [Internet]. 2020;12(9). Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32854251.

|

| 48. |

Thapar N, Eid MAF, Raj N, Kantas T, Billing HS, Sadhu D. Application of CRISPR/Cas9 in the management of Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease: a review. Ann Med Surg [Internet]. 2024;86(1):329–35. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38222734.

|

| 49. |

Pinjala P, Tryphena KP, Prasad R, Khatri DK, Sun W, Singh SB, et al. CRISPR/Cas9 assisted stem cell therapy in Parkinson’s disease. Biomater Res [Internet]. 2023;27(1):46. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37194005.

|

| 50. |

Hussein M, Molina MA, Berkhout B, Herrera-Carrillo E. A CRISPR-Cas Cure for HIV/AIDS. Int J Mol Sci [Internet]. 2023;24(2). Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36675077.

|

| 51. |

Bhowmik R, Chaubey B. CRISPR/Cas9: a tool to eradicate HIV-1. AIDS Res Ther [Internet]. 2022;19(1):58. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36457057.

|

| 52. |

Zhang Z, Hou W, Chen S. Updates on CRISPR-based gene editing in HIV-1/AIDS therapy. Virol Sin [Internet]. 2022;37(1):1–10. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35234622.

|

| 53. |

Najafi S, Tan SC, Aghamiri S, Raee P, Ebrahimi Z, Jahromi ZK, et al. Therapeutic potentials of CRISPR-Cas genome editing technology in human viral infections. Biomed Pharmacother [Internet]. 2022;148:112743. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35228065.

|

| 54. |

Ying M, Wang H, Liu T, Han Z, Lin K, Shi Q, et al. CLEAR Strategy Inhibited HSV Proliferation Using Viral Vectors Delivered CRISPR-Cas9. Pathog (Basel, Switzerland) [Internet]. 2023;12(6). Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37375504.

|