Abstract

Background: This study aimed to evaluate the relative length and anatomical position of septal papillary muscles, including the papillary muscle of the conus arteriosus (MCA) and other septal papillary muscles (MPS), as these may have significant clinical implications.

Material and methods: We examined 111 formalin-fixed human hearts from individuals aged 49-97 years, with no pathological lesions or malformations. The right ventricle was opened with a V-shaped incision, and measurements were taken along the posterior angle from the annulus fibrosus to the apex. The ventricle height was divided into ten levels for topographical assessment. Relative muscle lengths were calculated as percentages of ventricular height.

Results: MCA was present in all specimens, predominantly as a poorly developed structure (67.57% with relative length 1-5%). MPS were absent in 28 hearts, with only tendinous cords present. When developed, MPS showed similar proportions to MCA. The latter was primarily located at the third level from the annulus fibrosus, while MPS and associated cords showed greater topographical variability (levels 1-7).

Conclusions: Septal papillary muscles demonstrate considerable morphological and topographical variability. The predominance of poorly developed muscles and the presence of tendinous cords alone suggest evolutionary variations in septal muscular organization. These findings provide important anatomical insights for cardiac interventions.

Citation

Kosiński A, Kaczyńska A, Piwko G, Jeżyk D, Słonimska P, Zajączkowska K, Zawrzykraj M, Zajączkowski M. The length and topographical location of septal papillary muscles in adult human hearts. Eur J Transl Clin Med. 2025;8(2):25-34Introduction

Although not a new area of research, cardiac morphology remains indispensable in the dynamic development of interventional cardiology and cardiac surgery. Understanding the detailed anatomy of individual cardiac structures is essential for recognizing pathological variations that may occur within the heart. While modern visualization techniques provide valuable insights, comprehensive autopsy studies enable detailed morphological observations that remain crucial for clinical practice. Such studies may, among other things, help determine whether a specific configuration of a heart’s structure represents the norm (or its variant) or a pathology.

In 1863, Luschka described the muscle located on the heart’s septum and proposed the name “papillary muscle of the conus arteriosus” (musculus coni, MCA) [1]. Some controversies arise around this structure’s nomenclature. Some authors have used the above-mentioned term, although the terms “muscle of Luschka” or “muscle of Lancisi” are can also be found in the literature [2].

In recent years, relatively few research articles have focused on the septal papillary muscles (musculi papillares septales, MPS) that contribute to the valvular apparatus of the right atrioventricular orifice. Szostakiewicz-Sawicka, Wenink and Restivo et al. noticed the significant role of the muscles located in the immediate vicinity of the musculus coni as supportive elements to the anterior commisure and the cuspis septalis of the tricuspid valve [3-5]. For this reason, Wenink suggested the term “the medial papillary complex” which, with a slight modification („the medial papillary muscle complex”), is also used by Restivo [4-5]. According to these authors, the muscles constitute a complex directly connected with the muscle of the arterial cone. Loukas et al. stresses the researchers’ limited interest in MCA, although the knowledge of the heart’s normal anatomy is essential for the correct understanding of cardiac diseases [2].

The aim of this study was to estimate the relative length of all MPS, including the muscles of the arterial cone, as well as remaining septal muscles and the height at which the basis of the muscles are located, which may have significant clinical relevance.

Materials and methods

The observations were conducted on 111 human hearts of both sexes, from individuals aged 49-97 years, with no pathological lesions or malformations, fixed in a solution of formalin and ethanol. The hearts were obtained from the collection of the Division of Clinical Anatomy at the Medical University of Gdańsk (Poland). All experimental procedures were approved by the local Independent Bioethics Committee for Scientific Research (decision No. 74/2012).

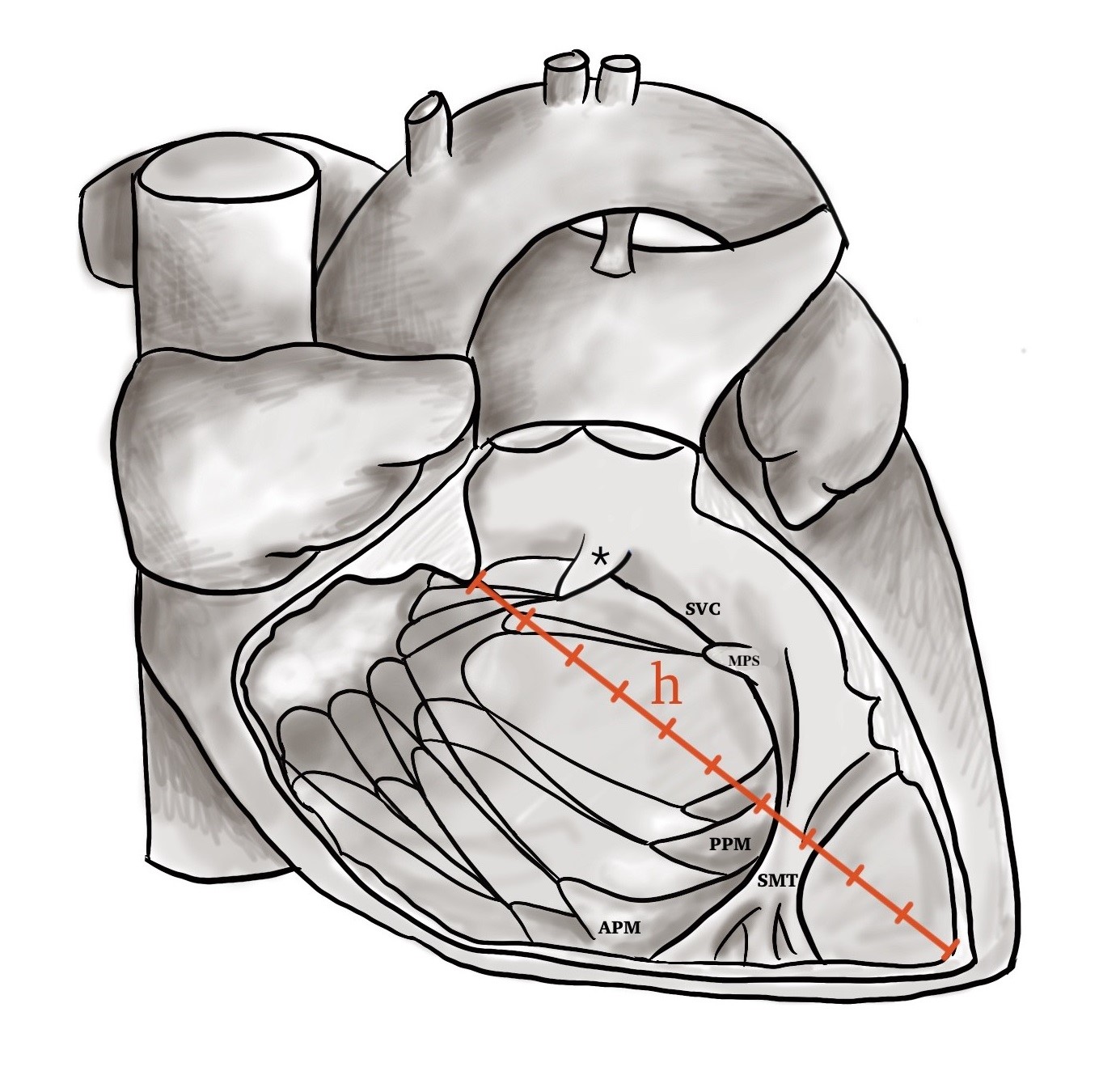

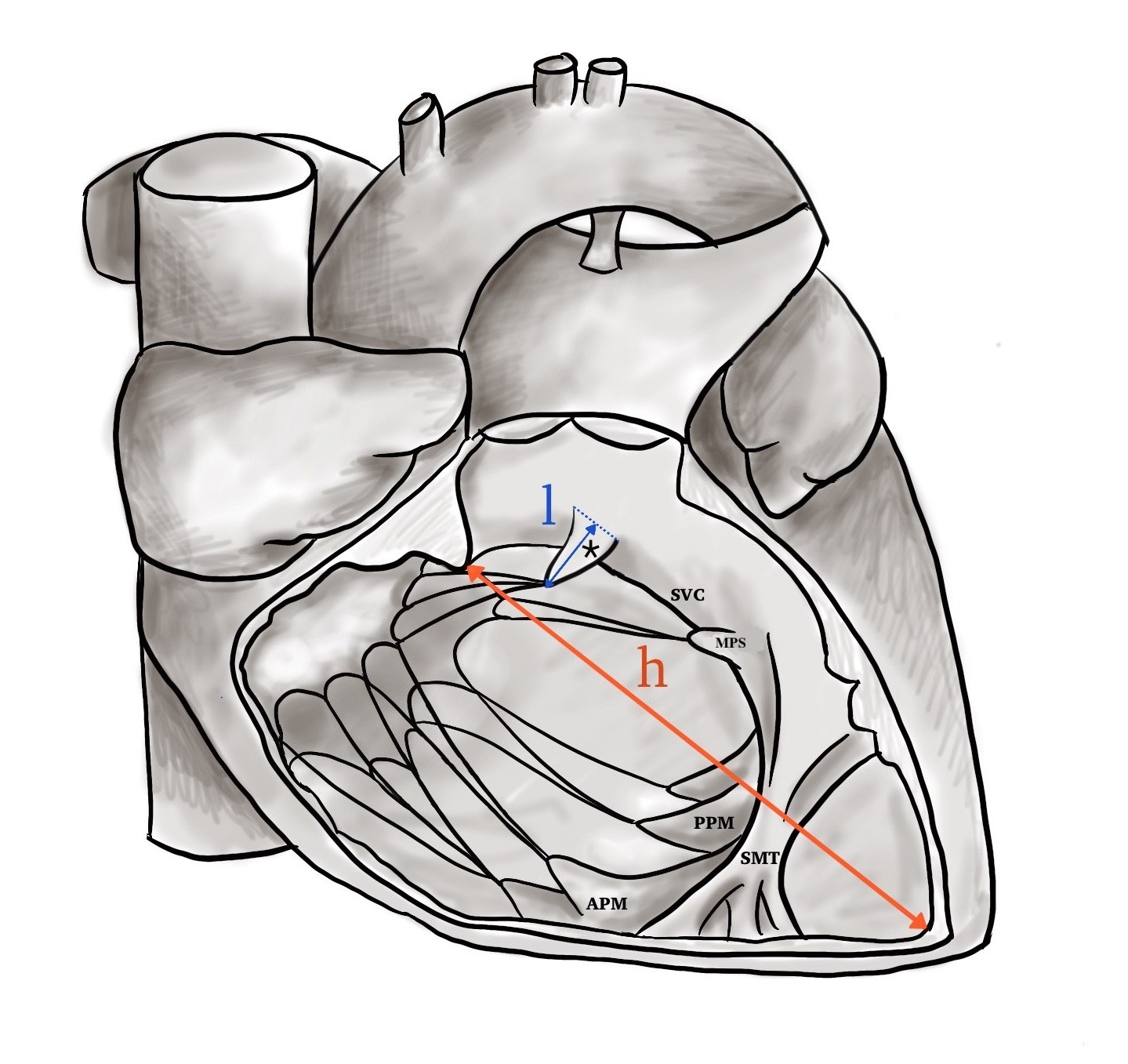

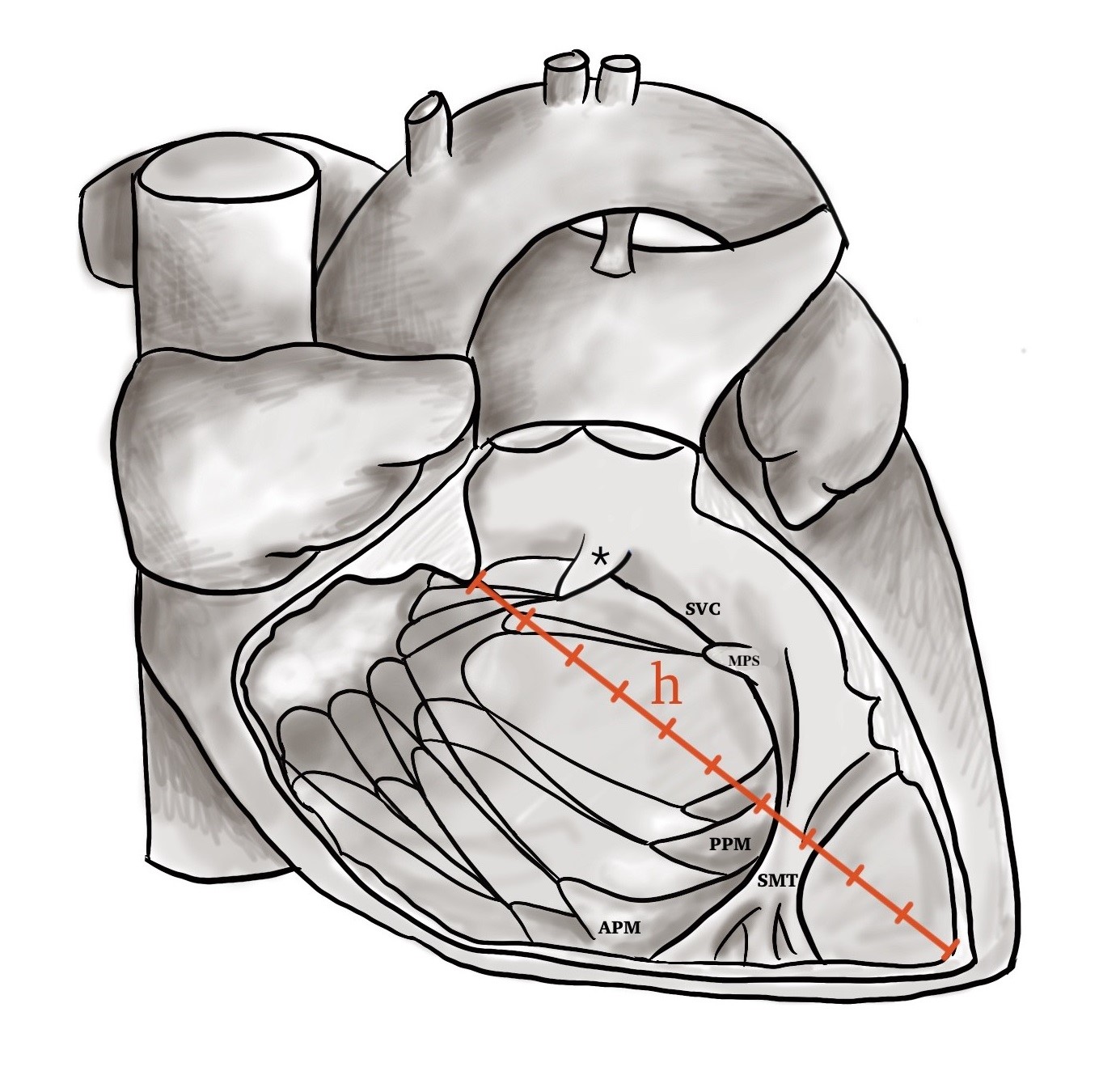

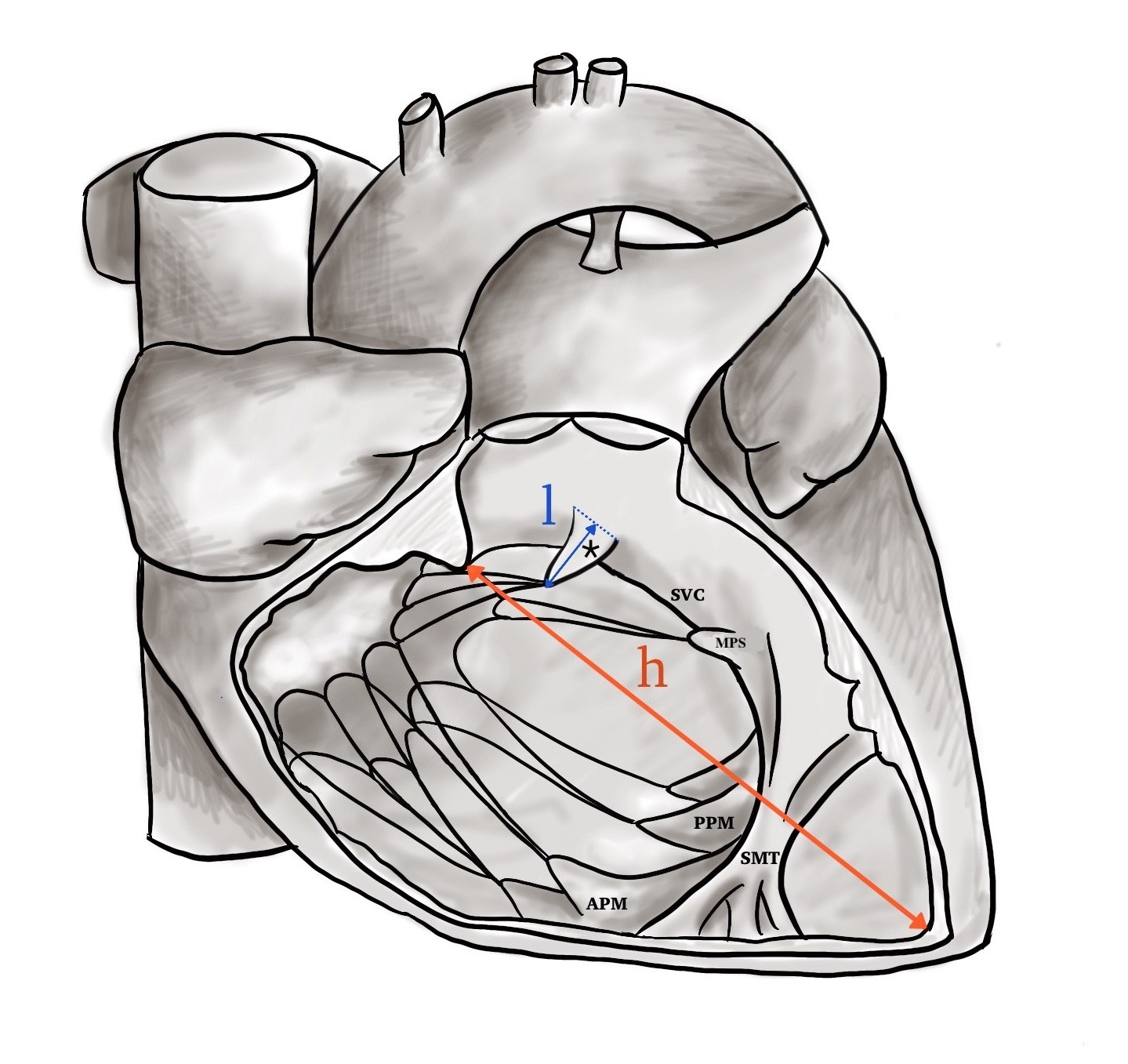

Classic anatomic methods were used: the right ventricle (RV) was opened with a V-incision from the aortic orifice of the pulmonary trunk (along the anterior interventricular groove), and then along the lateral border of the RV towards the right atrioventricular valve. The RV height was measured along its posterior angle: from the fibrous annulus of the tricuspid valve (FA) to the apex of the RV. The ventricular height was divided into ten equal levels (1-10, counted from FA towards the apex) serving for determining the height of location of the examined structures (Figure 1). Relative lengths of the muscles were measured and normalized to the height of the RV (Figure 2). These results were then categorized into the following ranges for analysis: 1-5%, 6-10%, 11-15%, 16-20%, and > 20%.

Figure 1. The division of interventricular septum into 10 levels

h – the height of the right ventricle; SVC – supraventricular crest; MPS – septal papillary muscles; MPP – posterior papillary muscle; APM – anterior papillary muscle; SMT – septomarginal trabecula; « – papillary muscle of the conus arteriosus

Figure 2. Relative height of the papillary muscles ( l/h )

l – the length of papillary muscle of the conus arteriosus; h – the height of the right ventricle; SVC – supraventricular crest; MPS – septal papillary muscles; MPP – posterior papillary muscle; APM – anterior papillary muscle; SMT – septomarginal trabecula; « – papillary muscle of the conus arteriosus

Statistical analysis

When evaluating the results, a non-parametric Pearson’s chi-square test of independence was used. The software used to perform analyses was R 2.15.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and GraphPad 5 (GraphPad Software, Inc. La Jolla California, USA). P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

All examined structures were divided into 2 groups, as suggested by Jeżyk et al.: “constant” (with MCA present in each specimen) and “variable” (included MPS) similarly to other papillary muscles, are essential elements of the heart valvular system [6]. Damage to their structure may lead to a considerable life risk. Of all the papillary muscles, the septal papillary muscles are characterized by the greatest topographical and morphological variability. However, information about these muscles is scarce and fragmentary. The objective of this study was to ascertain their occurrence and the region in which they are placed in the inter-ventricular septum. One hundred and eleven human hearts were examined. The hearts belonged to the Clinical Anatomy Department of the Medical University of Gdańsk. They were fixed in formalin with ethanol and came from middle-aged and older individuals of both sexes, devoid of pathological changes and birth defects. During the tests, classic anatomical methods were applied. The region where the papillary muscles are found covers a sizeable surface of the septum, from the conus arteriosus up to the back angle of the right chamber. Depending on their location the following septal papillary muscles (musculi papillares septales, MPS).

Relative length of MCA

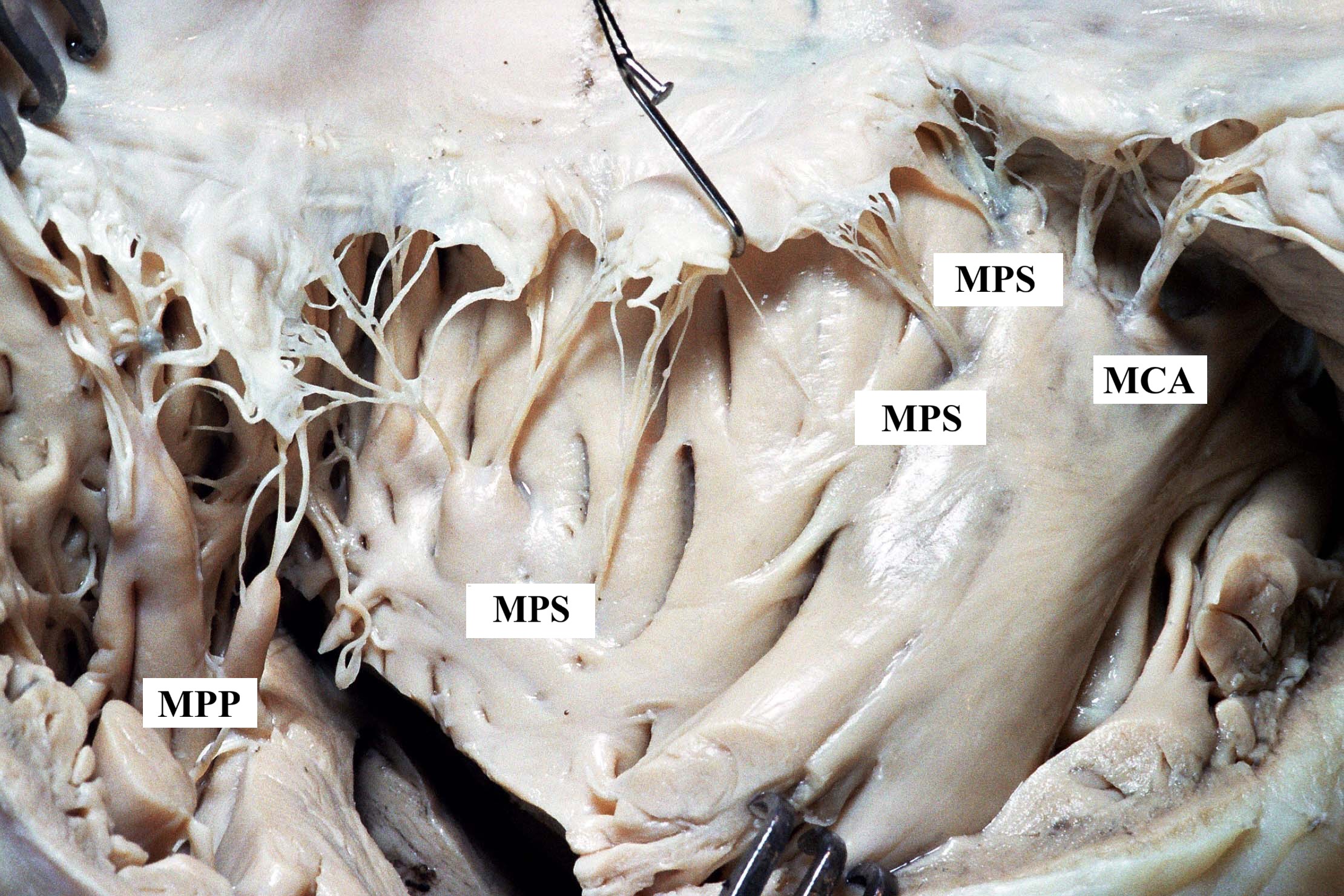

MCA was observed in all examined hearts. In most cases it was a poorly developed structure (of a relative length of 1-5%), constituting a minor convexity (Figure 3). In 3 hearts only, its relative length reached the highest value of 16-20% of the RV’s height. (Table 1).

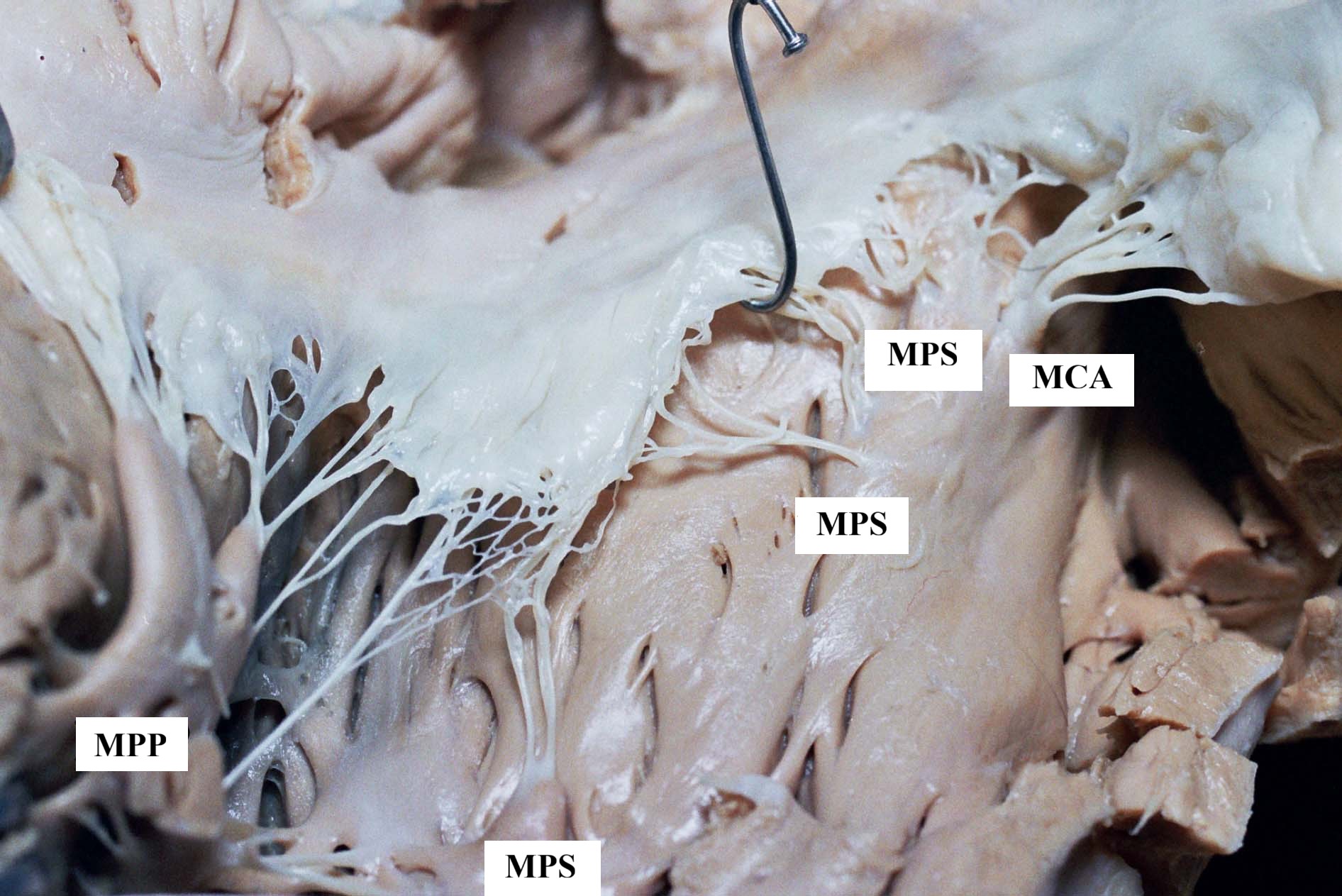

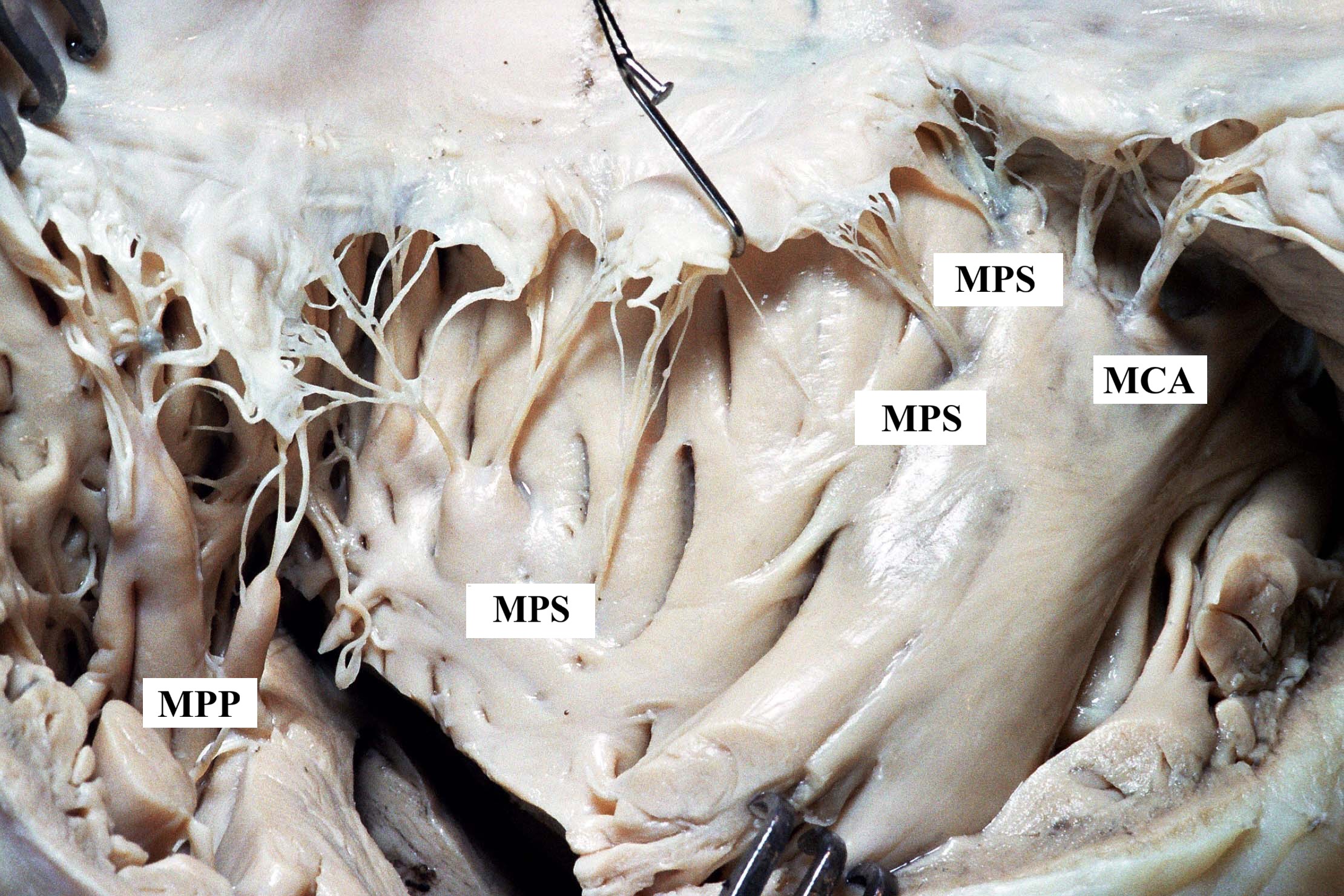

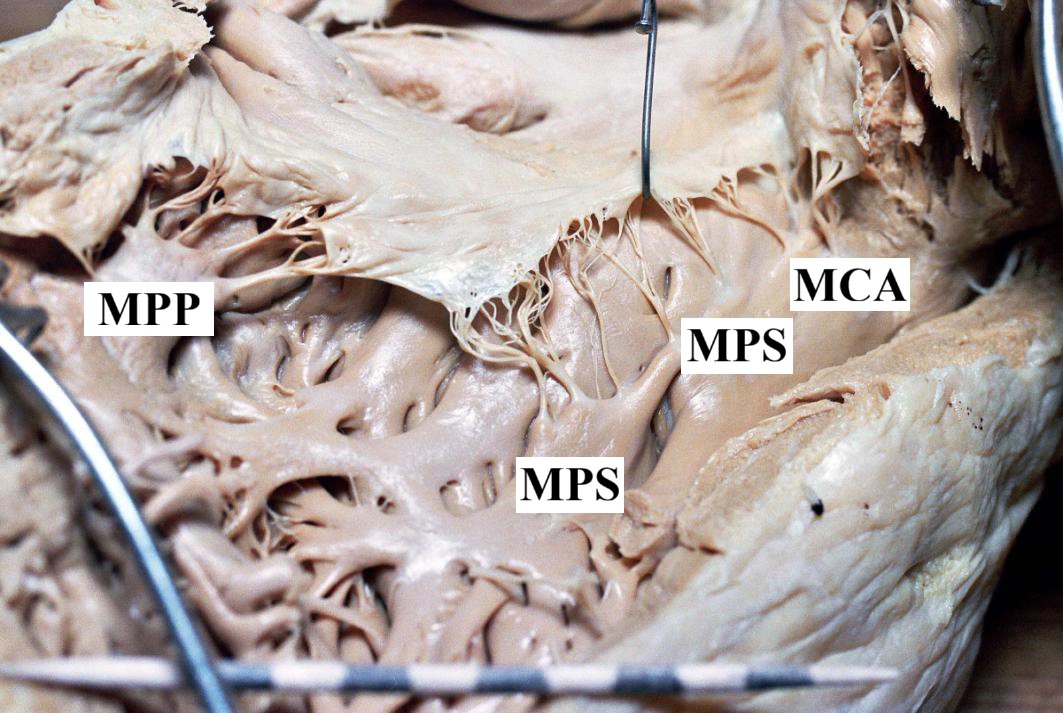

Figure 3. Gross anatomical view of the opened right ventricle in an adult human heart, showing the exposed cavity with papillary muscles. An example of a poorly developed MCA (relative length of 1-5%)

MPS – septal papillary muscles; MCA – papillary muscle of the conus arteriosus; MPP – posterior papillary muscle

Table 1. Relative length of MCA in adult human hearts expressed in percent of the ventricle’s height (ALMCA)

Relative length of MPS

MPS are generally poorly developed (Table 2). In 28 hearts (25.23%) we did not dermine the presence of MPS. In such cases only tendinous cords ran from the intraventricular septum and supplied specific parts of the tricuspid valve cusp. Developed muscles were of convex or conical shape, lying in the medial or posterior part of the septum in the vicinity of the posterior papillary muscle.

Table 2. Relative length of MPS in adult human hearts expressed in percent of the ventricle’s height (ALMPS)

As the above data indicate, very poorly developed MPS (with a relative length of 1-5%) clearly predominated, constituting the majority of cases and making up over 60% of all muscles observed. Comparing data related to the length of the MCA (Table 1) with the length of the MPS (Table 2), we might conclude that the value distribution for both muscles was alike (Figure 4). This is confirmed by Pearson’s chi-square analysis (Pearson’s) = 1.8095; df = 3; p value = 0.61.

Figure 4. Relative length of MCA and MPS in adult human hearts – summary

The height of location of MPS’ base on the intraventricular septum

In order to estimate the location of the MPS, the height of the right ventricle (previously divided into 10 equal levels) was used as the reference system for determining their position along the intraventricular septum. Particular muscles belonging to a certain level were observed.

The height of location of MCA’s base on the intraventricular septum

In most cases the MCA was located on the 3rd level of the FA (Figure 5).

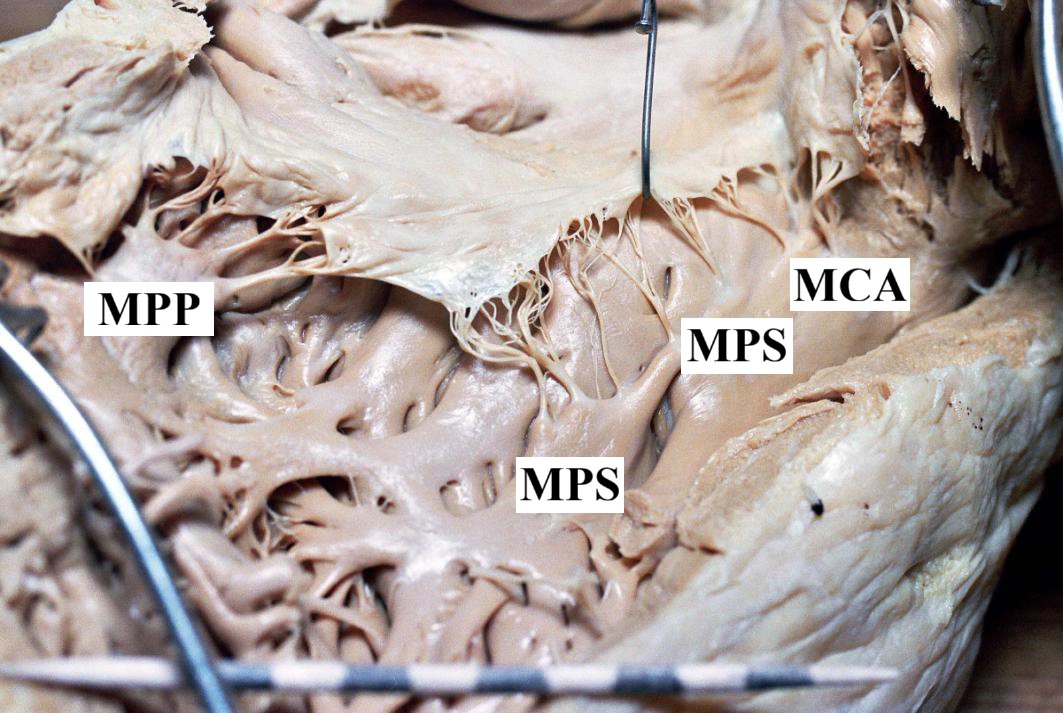

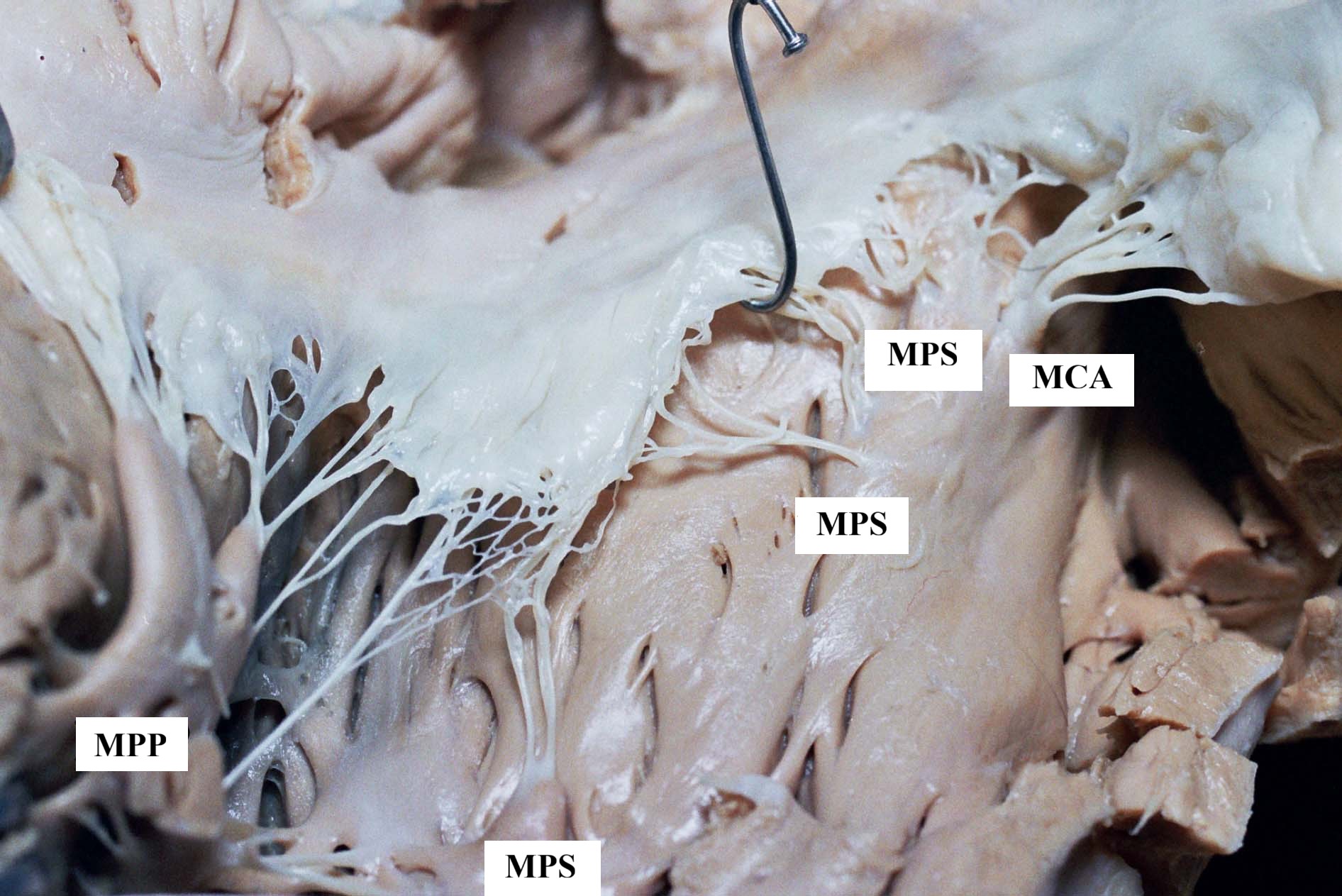

Figure 5. Gross anatomical view of the opened right ventricle in an adult human heart, showing the exposed cavity with papillary muscles

MPS – septal papillary muscles; MCA – papillary muscle of the conus arteriosus; MPP – posterior papillary muscle

The height of location of MPS’s base on the intraventricular septum

The observations revealed the presence of variable number of MPS muscles often accompanied by tendinous cords occurring in different proportion.

The muscles and / or the tendinous cords were mostly observed on upper levels, although they could also be found on the 6th and 7th levels (Figure 6). In total, 492 such structures were reported, of which 136 constituted the MPS, and 356 – the cords.

Figure 6. Gross anatomical view of the opened right ventricle in an adult human heart, showing the exposed cavity with papillary muscles

MPS – septal papillary muscles; MCA – papillary muscle of the conus arteriosus; MPP – posterior papillary muscle

The height of location of MPS’ base on the septum (and/or the height of the location of the tendinous cords diverging) is presented in Table 4.

When we compare the data from both tables, i.e. the height of the MCA base (Table 3) with the height of the MPS base (Table 4), we may conclude that the location of these muscles on the ventricular septum is variable (Figure 7) as confirmed by Pearson’s chi-square analysis (Pearson’s) = 155.676; df = 6; p value < 0.001.

Table 3. The height of the location of MCA’s base on intraventricular septum in adult human hearts

Table 4. The height of location of MPS’s base and/or corresponding tendinous cords on the intraventricular septum in adult human hearts

Figure 7. Height of the base of the MCA and MPS (and/or tendinous cords) in adult human hearts – summary

In 28 hearts MPS were not observed, although corresponding tendinous cords co-creating the valvular apparatus were present. In remaining 83 hearts we noted the presence of the total 136 MPS (Table 2). As already mentioned, the MPS were bound to the medial or posterior part of the septum, in the vicinity of the posterior papillary muscle. In total 356 tendinous cords were observed diverging directly from the septum and associated MPS. Some of them occurred alone with no developed MPS (28 hearts), other accompanied usually poorly developed muscles. The presence of various number of MPS muscles (often additionally accompanied by the cords), and even the presence of tendinous cords alone confirms the variability of this group of septal papillary muscles.

Discussion

Papillary muscles related to the septum constitute a part of the heart’s valvular apparatus, thereby co-deciding about its proper functioning [3, 7-12]. Therefore, understanding the detailed anatomy of the MPS complex is crucial not only for anatomical classification but also for clinical applications such as imaging interpretation, catheter-based interventions, and valve repair procedures. Their morphology can influence conduction pathways and arrhythmogenic potential in the right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) [10, 13-14]. Advanced cardiac CT and MRI have become the reference methods for examining the complex geometry of the RVOT, thereby enabling further study of sub-structures such as septal papillary muscles and their potential morphological impact [15]. Structural damage to these muscles can pose considerable clinical risk [16-18]. Nevertheless, some authors emphasize that the attention given to MPS complex of septal papillary muscles is still insufficient [2].

The substantial topographical and morphological diversity of MCA and MPS has led to nomenclature ambiguity [19-20]. Jeżyk et al. observed a specific distinction within the septal muscles: a fixed group and a variable one. In the former group they included an always-present muscle located anteriorly on the septum, which due to its location is often referred to as the muscle of the arterial cone (m. coni arteriosi or m. subarteriosus) (MCA). The attitudinally based approach to cardiac anatomy introduced by Anderson et al. [21] redefines papillary muscle orientation in terms of spatial relationships rather than traditional directional terminology. In the latest attitudinally based description of right ventricular anatomy by Crucean et al. [20] the papillary muscles are characterized according to their spatial relationships with the septal, inferior, and antero-superior leaflets of the tricuspid valve, reflecting their true topographical orientation within the RV. In the available literature, MCA was most often regarded as the MPS. Jeżyk et al. proposed a distinction in which this muscle (MCA) belongs to the constant group, whereas the remaining MPS form a variable group [6]. In previous reports, these additional MPS were inconsistently described as accessory muscles (m. accesorius) or as the septum’s own muscles (m. papillaris proprius septi) or were simply ignored. In our study, we adopted the same classification as Jeżyk et al. [6] similarly to other papillary muscles, are essential elements of the heart valvular system. Damage to their structure may lead to a considerable life risk. Of all the papillary muscles, the septal papillary muscles are characterized by the greatest topographical and morphological variability. However, information about these muscles is scarce and fragmentary. The objective of this study was to ascertain their occurrence and the region in which they are placed in the inter-ventricular septum. One hundred and eleven human hearts were examined. The hearts belonged to the Clinical Anatomy Department of the Medical University of Gdańsk. They were fixed in formalin with ethanol and came from middle-aged and older individuals of both sexes, devoid of pathological changes and birth defects. During the tests, classic anatomical methods were applied. The region where the papillary muscles are found covers a sizeable surface of the septum, from the conus arteriosus up to the back angle of the right chamber. Depending on their location the following septal papillary muscles (musculi papillares septales, MPS. According to this classification, the absence of a developed muscle was recorded as a tendinous cord.

In the available literature, authors typically use absolute values to estimate the length of papillary muscles [5, 16, 22]. Whereas, the relative length of the muscles, as used in this study, may provide a basis for broadening the scope of observations through comparative anatomical studies. Expressing muscle length in proportion to the ventricular height reflects its potential mechanical influence on leaflet tethering and right ventricular geometry. This proportional analysis is conceptually consistent with parameters used in previous experimental and clinical studies to predict residual tricuspid regurgitation, where altered papillary muscle positioning and tethering angles have been shown to correlate with postoperative outcomes [14, 23-24]. Therefore, this method may offer functionally relevant insight into the interplay between septal muscle morphology and tricuspid valve competence. The relative height used in such studies provides for differences within the size of particular hearts. Further discussion is needed to determine whether “muscle height” rather than “muscle length” would be a more appropriate term for the septal papillary muscles. In this study we used the former term. Topographic relations and the term “ventricle’s height” used in the work as a point of reference, might support the former interpretation. However, we decided to use the latter term since it occurs in available literature, although referring to absolute values.

Huwyler figuratively described the size of the MCA in human hearts reporting that it reaches at most the dimension of a cherry stone, whereas Rouviere presented it as a small, conical muscle located above the moderator band [25-26]. Although most of the previous studies have focused on morphological and gross shape variations, our analysis extends this approach by offering a more detailed quantitative comparison of relative papillary muscle lengths [27]. This approach complements previous morphometric investigations by introducing a normalized assessment of septal papillary muscle dimensions relative to the RV height, enabling inter-individual comparison independent of heart size.

Saha and Roy reported the mean length of the septal papillary muscle as 0.95 ± 0.38 cm, typically arising from the upper one-third of the RV, whereas Sinha et al. observed a comparable mean value of 0.92 ± 0.54 cm[28-29]. Our findings are consistent with these observations. Farzana et al. noted an age-related increase in the muscle’s mean length, from 0.51 cm in young adults to 0.81 cm in older individuals [30]. Bhadoria reported that all septal papillary muscles were uniformly conical in shape in all 50 (100%) hearts examined in their study [31]. Varghese described them as having a conical or broad-apex shape. He does not describe any cylindrical muscles on the septum [32]. Testut et al., described the muscle of the arterial cone as a round hump of 6-8 mm in length, often occurring at a site, where the supraventricular crest descends [33]. In turn, Mikhaylov wrote that the length of MCA in his material ranged from 2 to 14 mm, and the height of most muscles amounted from 2 to 6 mm, whereas Musso reported the dimension of 4 to 18 mm [16, 22].

Both MCA and MPS were in most cases observed as poorly developed structures. This was also confirmed by statistical analysis. Contemporary anatomical and electrophysiological studies describe marked variability in the development of right ventricular papillary muscles, therefore good anatomical knowledge is required [34]. The right ventricle can be separated into an inlet, an outlet, and an apical compartment. The inlet and outlet are separated by the septomarginal trabeculae, while the apex is situated below the moderator band. A lead position in the right ventricular apex is less desirable, last but not least due to the thin myocardial wall. Many leads supposed to be implanted in the apex are in fact fixed rather within the trabeculae in the inlet, which are sometimes difficult to pass. In the RVOT the septal papillary muscle is typically the least prominent element of the right ventricular apparatus and may even be absent as a distinct structure (reported absent in ~56% of specimens) [28]. After examining 30 adult human hearts Szostakiewicz-Sawicka described MCA as little convexities and in 3 cases reported their absence. In our material MCA was always present [3].

This considerable variability may explain the relatively limited number of publications devoted to these structures and the difficulties in their classification. For this reason their name is seldom mentioned in literature or referred only as to ‘small muscles’, ‘minor cones’ or ‘free and direct cords’ [35-37]. Considerable individual variation in the arrangement of tricuspid valve papillary muscles has been described, reinforcing that the so-called ‘normal’ configuration may vary widely among healthy individuals [38].

The anatomical variability of the septal papillary muscles, particularly within the conal region, may also influence the pathophysiology of arrhythmias arising from the RVOT. Knowledge of the individual papillary muscle anatomy is crucial for successful catheter-based treatment, as the complex structure and variability of these muscles directly affect catheter stability, mapping accuracy, and long-term ablation outcomes. Despite continuous technical progress, the long-term success of papillary muscle ablation remains moderate, highlighting the importance of precise anatomical understanding before intervention [39]. Accurate knowledge of this part of the heart is also essential for effective ablation and prevention of iatrogenic injury [10, 13].

Beyond their arrhythmogenic relevance, variations in the septal papillary muscles may affect tricuspid valve mechanics and contribute to leaflet tethering in functional regurgitation or dilated cardiomyopathy. Studies have demonstrated that tethering angles and septal muscle displacement predict recurrence of tricuspid regurgitation after surgical repair [23-24, 40]. Hence, the structural variability described in our study could have direct implications for preoperative imaging and repair strategy. This variability may also be reflected in a slightly less stable attachment of these structures along the septum. While the MCA occupied mainly the 3rd level (from 2 to 4) (Table3), the MPS +/- the corresponding cords were most frequently observed between levels 1 and 7, predominantly in the upper levels (Table 4). Statistical analysis confirmed the variability of the levels of both muscles’ location (including tendinous cords) on the septum. Particular muscles constituting a complex of papillary muscles of a relevant group in the RV are called “heads” by Nigri et al. [41]. It seems that these authors included a part of the papillary muscles complex into the posterior papillary muscle group. They also distinguished various types of the muscles’ shapes: conical, flat-topped, mammillated, arched. It can be assumed that the authors accommodated different criteria for the muscles’ valuation.

The high frequency of poorly developed or absent septal papillary muscles suggests that this structure cannot be regarded as a constant anatomical landmark. This finding contrasts with traditional anatomical descriptions, highlighting a greater degree of variability than previously recognized [31, 42].

Conclusions

In summary, the considerable variability in the morphology and location of septal papillary muscles has important implications for right ventricular geometry, tricuspid valve function, and RVOT arrhythmogenicity. The present correlations between relative muscle length, attachment height, and functional relevance underscore the clinical importance of these structures in imaging, surgery, and electrophysiology.

The frequent finding of poorly developed muscles located on the interventricular septum (or even replacement by tendinous cords) appears particularly noteworthy, as these may represent vestigial remnants of septal papillary muscles. Future studies combining gross anatomy with histological and microstructural analyses would help clarify whether these formations reflect regressed remnants or functionally specialized components, and how their tissue composition may influence subtle variations in right ventricular mechanics.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding

None.

References

| 1. |

von Luschka H. Die Anatomie der Brust des Menschen. Verlag der H. Laupp’schen Buchhandlung; 1863.

|

| 2. |

Loukas M, Shane Tubbs R, Louis RG, Apaydin N, Bartczak A, Huseng V, et al. An endoscopic and anatomical approach to the septal papillary muscle of the conus. Surg Radiol Anat [Internet]. 2009;31(9):701–6. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00276-009-0510-2.

|

| 3. |

Szostakiewicz-Sawicka H. Zastawka przedsionkowo-komorowa prawa u naczelnych. Rozprawa habilitacyjna. Acta Biol Med Soc Sc Gedan. 1967;11:545–89.

|

| 4. |

Wenink AC. The medial papillary complex. Br Heart J [Internet]. 1977 Sep 1;39(9):1012 LP – 1018. Available from: http://heart.bmj.com/content/39/9/1012.abstract.

|

| 5. |

Restivo A, Smith A, Wilkinson JL, Anderson RH. The medial papillary muscle complex and its related septomarginal trabeculation. A normal anatomical study on human hearts. J Anat [Internet]. 1989;163:231–42. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2606775.

|

| 6. |

Jeżyk D, Duda B, Jerzemowski J, Grzybiak M. Positions of septal papillary muscles in human hearts. Folia Morphol (Warsz). 2010;69(2):101–6.

|

| 7. |

Anzola J. Right Ventricular Contraction. Am J Physiol Content [Internet]. 1956;184(3):567–71. Available from: https://www.physiology.org/doi/10.1152/ajplegacy.1956.184.3.567.

|

| 8. |

Gould SE. Pathology of the heart and blood vessels. (No Title). 1968;.

|

| 9. |

Brandt W. The closing mechanism of the tricuspidal valve in the human heart. Cells Tissues Organs. 1957;30(1–4):128–32.

|

| 10. |

HAI JJ, DESIMONE C V., VAIDYA VR, ASIRVATHAM SJ. Endocavitary Structures in the Outflow Tract: Anatomy and Electrophysiology of the Conus Papillary Muscles. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol [Internet]. 2014;25(1):94–8. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jce.12291.

|

| 11. |

Josowitz R, Rogers LS. Double outlet right ventricle–the 50% rule has always been about the conus. Curr Opin Cardiol [Internet]. 2024;39(4):348–55. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/co-cardiology/_layouts/15/oaks.journals/downloadpdf.aspx?an=00001573-202407000-00019.

|

| 12. |

Xalxo N, Kaur S, Chauhan M, Sharma E, Sophia L, Agarwal S, et al. Papillary muscles: morphological differences and their clinical correlations. Anat Cell Biol [Internet]. 2025;58(1):44–53. Available from: https://acbjournal.org/journal/view.html?doi=10.5115/acb.24.210.

|

| 13. |

Naksuk N, Kapa S, Asirvatham SJ. Spectrum of Ventricular Arrhythmias Arising from Papillary Muscle in the Structurally Normal Heart. Card Electrophysiol Clin [Internet]. 2016;8(3):555–65. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccep.2016.04.005.

|

| 14. |

Kaczyńska A, Kosiński A, Kamiński R, Zajączkowski M, Nowicka E, Gleinert-Rożek M. A novel approach to visualization of the right ventricular outflow tract. Eur J Transl Clin Med [Internet]. 2019;1(2):36–40. Available from: https://ejtcm.gumed.edu.pl/articles/22.

|

| 15. |

Saremi F, Ho SY, Cabrera JA, Sánchez-Quintana D. Right Ventricular Outflow Tract Imaging With CT and MRI: Part 1, Morphology. Am J Roentgenol [Internet]. 2013;200(1):W39–50. Available from: http://www.ajronline.org/doi/abs/10.2214/AJR.12.9333.

|

| 16. |

Mikhaylov SS. Klinicheskaya anatomiya serdtsa [in Russian] (Clinical Anatomy of the Heart]=). Moscow: Medicina; 1987.

|

| 17. |

PASIC M, VONSEGESSER L, CARREL T, JENNI R, TURINA M. Severe tricuspid regurgitation following blunt chest trauma: indication for emergency surgery. Eur J Cardio-Thoracic Surg [Internet]. 1992;6(8):455–7. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/ejcts/article-lookup/doi/10.1016/1010-7940(92)90073-7.

|

| 18. |

Kozłowski D, Dubaniewicz A, Koźluk E, Grzybiak M, Krupa W, Kołodziej P, et al. The morphological conditions of the permanent pacemaker lead extraction. Folia Morphol (Warsz). 2000;59(1):25–9.

|

| 19. |

Kaçar D, Barut Ç. Conus arteriosus: an anatomic and terminologic evaluation. Anatomy [Internet]. 2014;8:40–4. Available from: http://dergipark.gov.tr/doi/10.2399/ana.11.213.

|

| 20. |

Crucean A, Spicer DE, Tretter JT, Mohun TJ, Anderson RH. Revisiting the anatomy of the right ventricle in the light of knowledge of its development. J Anat [Internet]. 2024;244(2):297–311. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/joa.13960.

|

| 21. |

Anderson RH, Spicer DE, Hlavacek AJ, Hill A, Loukas M. Describing the Cardiac Components—Attitudinally Appropriate Nomenclature. J Cardiovasc Transl Res [Internet]. 2013;6(2):118–23. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s12265-012-9434-z.

|

| 22. |

Musso F, Rodrigues H, Anderle DV, Dalfior Junior L, Marim T. Morphology and blood supply of papillary muscle in the arterial conus. Braz j morphol sci [Internet]. 2000;137–40. Available from: https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/portal/resource/pt/lil-313971.

|

| 23. |

Yamauchi H, Vasilyev N V., Marx GR, Loyola H, Padala M, Yoganathan AP, et al. Right ventricular papillary muscle approximation as a novel technique of valve repair for functional tricuspid regurgitation in an ex vivo porcine model. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg [Internet]. 2012;144(1):235–42. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0022522312000542.

|

| 24. |

Couetil J-P, Nappi F, Spadaccio C, Fiore A. Papillary muscle septalization for functional tricuspid regurgitation: Proof of concept and preliminary clinical experience. JTCVS Tech [Internet]. 2021;10:282–8. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S266625072100657X.

|

| 25. |

Huwyler B. Zur Anatomie des Schweineherzens. Anat Anz. 1926;62:49–76.

|

| 26. |

Rouviere H. Anatomia Humana – Descriptiva Y Topografica. 8th ed. Madrit: Casa Editorial Bailly-Bailliere, SA; 1961.

|

| 27. |

Gheorghitescu (Janca) Ruxandra, Toba M, Iliescu DM, Bordei P. Morphological features of papillary muscles in the right ventricle. ARS Medica Tomitana [Internet]. 2016;22(3):135–44. Available from: https://www.sciendo.com/article/10.1515/arsm-2016-0023.

|

| 28. |

Saha A, Roy S. Papillary muscles of left ventricle — Morphological variations and it’s clinical relevance. Indian Heart J [Internet]. 2018;70(6):894–900. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0019483217305539.

|

| 29. |

Sinha MB, Somkuwar SK, Kumar D, Sharma DK. Anatomical variations of papillary muscles in human cadaveric hearts of Chhattisgarh, India. Indian J Clin Anat Physiol [Internet]. 2021;7(4):374–80. Available from: https://ijcap.org/article-details/13034.

|

| 30. |

Farzana T, Khalil M, Mannan S, Sultana J, Sumi MS, Sultana R. Length of papillary muscles in both ventricles of different age group on Bangladeshi cadaver. Mymensingh Med J [Internet]. 2015;24(1):52–8. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25725668.

|

| 31. |

Bhadoria P, Bisht K, Singh B, Tiwari V. Cadaveric Study on the Morphology and Morphometry of Heart Papillary Muscles. Cureus [Internet]. 2022; Available from: https://www.cureus.com/articles/83366-cadaveric-study-on-the-morphology-and-morphometry-of-heart-papillary-muscles.

|

| 32. |

Varghese G, Setiya M. Morphological and Morphometric Study of Papillary Muscles in Adult Cadaveric Hearts: A Crosssectional Study from Central India. J Clin DIAGNOSTIC Res [Internet]. 2025; Available from: https://www.jcdr.net/article_fulltext.asp?issn=0973-709x&year=2025&month=July&volume=19&issue=7&page=AC01-AC04&id=21242.

|

| 33. |

Testut L, Latarjet A. Traité d’anatomie humaine: Angéiologie. Gaston Doin; 1929.

|

| 34. |

Israel CW, Tribunyan S, Yen Ho S, Cabrera JA. Anatomy for right ventricular lead implantation. Herzschrittmachertherapie + Elektrophysiologie [Internet]. 2022;33(3):319–26. Available from: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00399-022-00872-w.

|

| 35. |

Bargman W, Doerr W. Das Herz des Menschen. Stuttgart: G. Thieme; 1963.

|

| 36. |

Netter FH. Atlas of Human Anatomy. 7th ed. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2019.

|

| 37. |

Schummer A, Nickel R, Seiferle E. Lehrbuch der Anatomie der Haustiere. 3rd ed. Berlin: Parey; 1976.

|

| 38. |

Aktas EO, Govsa F, Kocak A, Boydak B, Yavuz IC. Variations in the papillary muscles of normal tricuspid valve and their clinical relevance in medicolegal autopsies. Saudi Med J [Internet]. 2004;25(9):1176–85. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15448762.

|

| 39. |

Mariani MV, Piro A, Magnocavallo M, Chimenti C, Della Rocca D, Santangeli P, et al. Catheter ablation for papillary muscle arrhythmias: A systematic review. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol [Internet]. 2022;45(4):519–31. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/pace.14462.

|

| 40. |

Kabasawa M, Kohno H, Ishizaka T, Ishida K, Funabashi N, Kataoka A, et al. Assessment of functional tricuspid regurgitation using 320-detector-row multislice computed tomography: Risk factor analysis for recurrent regurgitation after tricuspid annuloplasty. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg [Internet]. 2014;147(1):312–20. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0022522312013943.

|

| 41. |

Nigri GR, Di Dio LJA, Baptista CAC. Papillary muscles and tendinous cords of the right ventricle of the human heart morphological characteristics. Surg Radiol Anat [Internet]. 2001;23(1):45–9. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00276-001-0045-7.

|

| 42. |

Wysoczański J, Zaborowski G, Anczyk A, Handzel K, Karaś R, Lepich T, et al. Anatomical and clinical aspects of the papillary muscles. Med Stud [Internet]. 2024;40(3):279–88. Available from: https://www.termedia.pl/doi/10.5114/ms.2024.142945.

|