Sexual satisfaction, quality of life and level of social support of women before, during and after pregnancy

Abstract

Introduction: Quality of life, social support and sexual satisfaction may change across life stages. The aim of this study was to assess these variables in women before, during and after pregnancy.

Material and methods: The study was cross-sectional, and conducted online among three independent groups of women (N = 160). Standardized tools were used: the WHOQOL-BREF quality of life questionnaire, Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), and Berlin Social Support Scales (BSSS). Statistical analysis was performed using nonparametric tests (Kruskal-Wallis, Mann-Whitney U, Friedman and chi-square tests).

Results: The highest level of sexual satisfaction, quality of life, and social support (p 0.05). A statistically significant relationship was demonstrated between the level of support from loved ones and satisfaction with intimate life (χ² = 21.974, p = 0.038).

Conclusions: Women’s sexual satisfaction, quality of life and social support vary, taking on different values before, during and after pregnancy. It is important to consider women’s needs at each stage to provide them with appropriate support and care.

Citation

Łaczyńska W, Milska-Musa K A. Sexual satisfaction, quality of life and level of social support of women before, during and after pregnancy. Eur J Transl Clin Med. 2025;8(1):71-82Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), sexual health is “a state of physical, emotional, mental and social well-being in relation to sexuality; it is not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction or infirmity.” Looking at this multifaceted definition, it is worth assessing sexual satisfaction in relation to quality of life (QoL) and level of social support, because these are factors that interact [1-2]. Women at different times in their lives may feel different emotions, experience different sensations in both the physical and mental sphere. The greatest number of physiological, hormonal and emotional changes that affect the QoL and sexual life of women can be observed during pregnancy and motherhood [3]. Using the results of the National Sexuality Report 2024, it can be stated that more than half of our society considers sex to be very important to them, while about 1/5 of respondents do not talk about sex at all [4]. The process of transition to motherhood may be associated with a number of challenges. On a sample of 398 respondents Fuchs et al. showed that pregnancy and childbirth significantly reduce women’s sexual activity [5]. Similar conclusions were also reached by scientists who analyzed the effect of childbirth on women’s sexuality in the first year after childbirth [6]. Studies show that satisfaction with women’s sexual life during pregnancy and after childbirth is significantly related to the social support they receive, relationships during pregnancy differ from those before pregnancy, and life satisfaction increases after the birth of a child [7]. Support from a partner, family and medical personnel significantly affects the emotional state and mental health of women during pregnancy and motherhood [8-9]. It has been shown that women after childbirth experience not only a decrease in the level of sexual pleasure and emotional intimacy, but also changes in their body image [10-11].

The quality of a partnership relationship may be determined by many factors. It has been shown that the partner’s involvement in household chores and the opportunity to spend personal time significantly affect the quality of the relationship and women’s mental health [11]. Moreover, a study conducted on a sample of 1652 married couples demonstrated that greater involvement of husbands in household chores was associated not only with the aforementioned better mental health of wives, overall happiness and also with lower levels of marital dissatisfaction [12]. It was also shown that couples who devote time to common conversations and activities show higher levels of relationship satisfaction and greater emotional intimacy [13].

An equally important factor, often omitted in research, that may affect women’s sexuality after childbirth are obstetric interventions, such as episiotomy or episiotomy. Studies indicate that such injuries may lead to pain during intercourse, a decreased sense of attractiveness, and fear of resuming sexual activity [14-15].

The aim of the study was to analyze sexual satisfaction, QoL and level of social support of women at three moments of life: before pregnancy, during pregnancy and after childbirth. We made an effort to study the topic in a cohort of women before pregnancy, during pregnancy and after childbirth in 3 independent groups to analyze differences and similarities between key stages of reproductive life.

Specifically, we aimed to test the following 3 hypotheses:

1. There are statistically significant differences between groups of women before pregnancy, during pregnancy and after childbirth in terms of social support, QoL and sexual functioning.

2. Episiotomy or laceration significantly affects the perception of the respondents’ sexuality.

3. Support from loved ones is associated with higher levels of sexual satisfaction.

Material and methods

We conducted this study was conducted online using the Google Forms software (Google LLC, Mountain View, USA). The desired participant age range was 18-35 years. Participants were recruited on the social networking site Facebook, in Polish-language groups dedicated to women trying to conceive, pregnant women and mothers. Participation in the study was anonymous and voluntary. After giving their consent, respondents were invited to participate in the study and received a survey containing questions in the Polish language about basic socio-demographic data, which consisted of a total of 7 sections. The first part was a section of original general socio-demographic questions, followed by 3 sections of original specific questions dedicated to women before pregnancy, during pregnancy and after childbirth. Then, all respondents completed the next 3 sections containing the following questionnaire tools: WHOQOL-BREF, Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) and Berlin Social Support Scales (BSSS). Their internal reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient and the obtained results were compared with data from the original validations.We also analysed the influence of the period of life on women’s sense of attractiveness and sexual experiences as well as obstacles to achieving sexual satisfaction during pregnancy.

The WHOQOL-BREF is a shortened 26-item questionnaire for assessing the QoL in 4 domains (physical, psychological, social relationships and environmental), reliability of the questionnaire developed by WHOQOL Group (1998), overall reliability in validation studies was α = 0.89, with values α = 0.68-0.82 for individual domains [16].

The FSFI is a scale developed by Rosen et al. assessing 6 domains of female sexual functioning: desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, sexual satisfaction and pain during intercourse in relation to the last 4 weeks. The reliability of the FSFI scale in the original study showed very high internal consistency: Cronbach’s α values in individual domains ranged from 0.82 to 0.94, and for the entire scale α = 0.97 [17].

The BSSS was developed by Schwarzer and Schutz to assess social support and we used the Polish version by Łuszczyńska and Kowalska [18]. It contains 17 general statements concerning the following subscales: Perceived Available Emotional Support, Perceived Available Instrumental Support, Need for Support and Seeking Support. The rest of the tool contains 15 statements referring to the person closest to the respondent, referring to Received Emotional Support, Received Instrumental Support and Received Informational Support. The third (optional) part of the Scales (Currently provided support) is dedicated to the person providing support and was not used in this study. The participants respond to each item by choosing 1 of 4 answers (from “completely true” to “completely false”).

The respondents’ sense of attractiveness after childbirth was assessed based on an original question included in the part of the questionnaire dedicated to women after childbirth: “Do you feel less physically attractive after childbirth than before?” Their responses were provided on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (“definitely not”) to 5 (“definitely yes”), with a higher score indicating a greater decrease in the sense of attractiveness.

Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, USA) and IBM SPSS (Armonk, NY, United States) software as well as a script written in the Python language (Python Software Fundation, Wilmington, Delaware, USA). The tests of normal distribution we conducted depending on the size of the selected group (Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk) did not show distributions consistent with the normal distribution among the analyzed variables. Therefore, we verified our hypotheses using non-parametric tests: Kruskal-Wallis H, Mann-Whitney U, Friedman and chi-square.

In order to identify factors influencing the level of sexual satisfaction of women, a multiple regression analysis was performed. The dependent variable was the total score on the FSFI scale (FSFI_Total). The model included clinical variables: episiotomy, type of delivery, change in sexual feelings after delivery and sense of attractiveness. Additionally, the level of social support (BSSS) was taken into account. The analysis used the OLS linear model (ordinary least squares), using the Python software. The level of statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05. Consent to conduct this study was obtained from the Independent Bioethics Committee for Scientific Research at the Medical University of Gdańsk (KB/97/2024).

Results

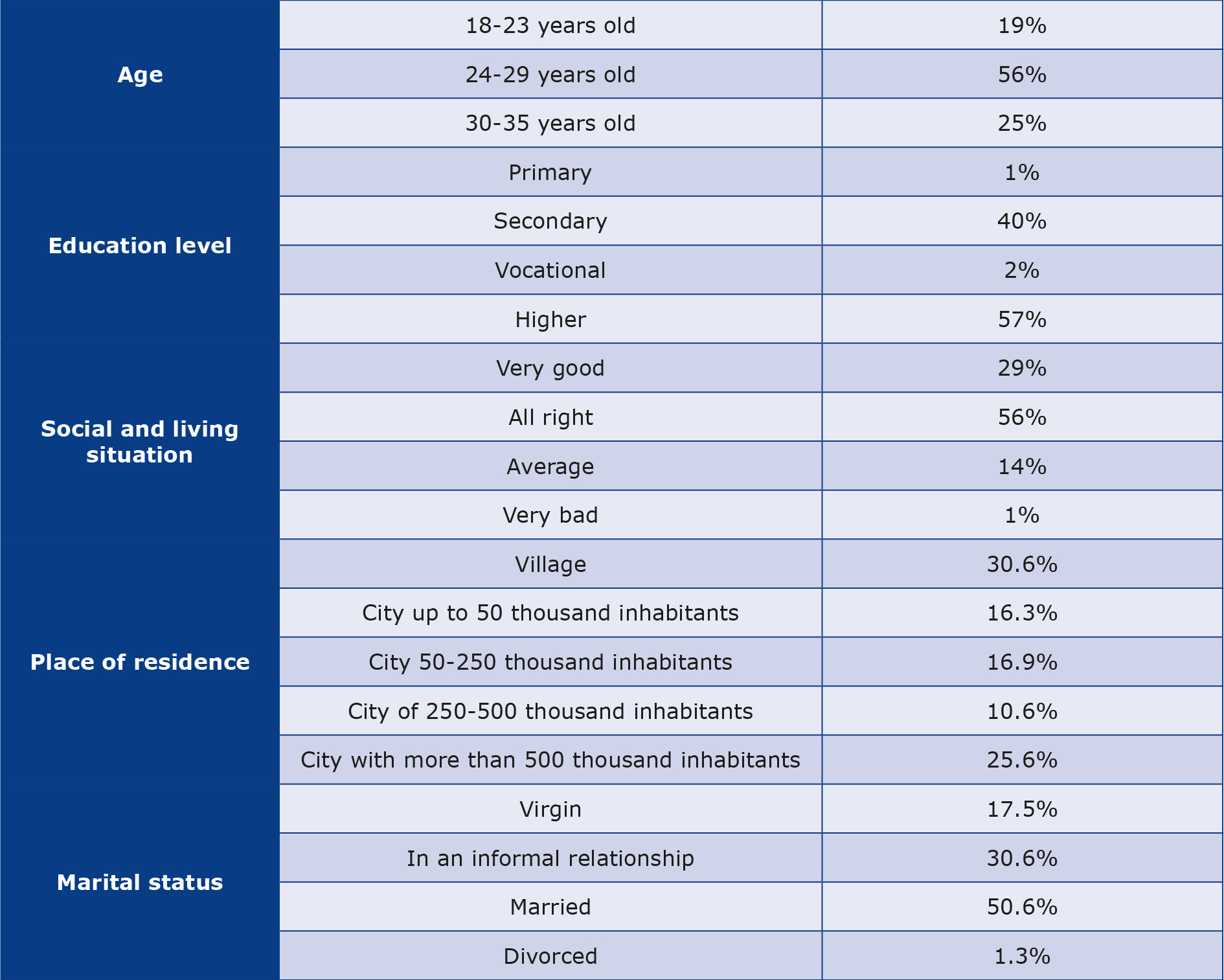

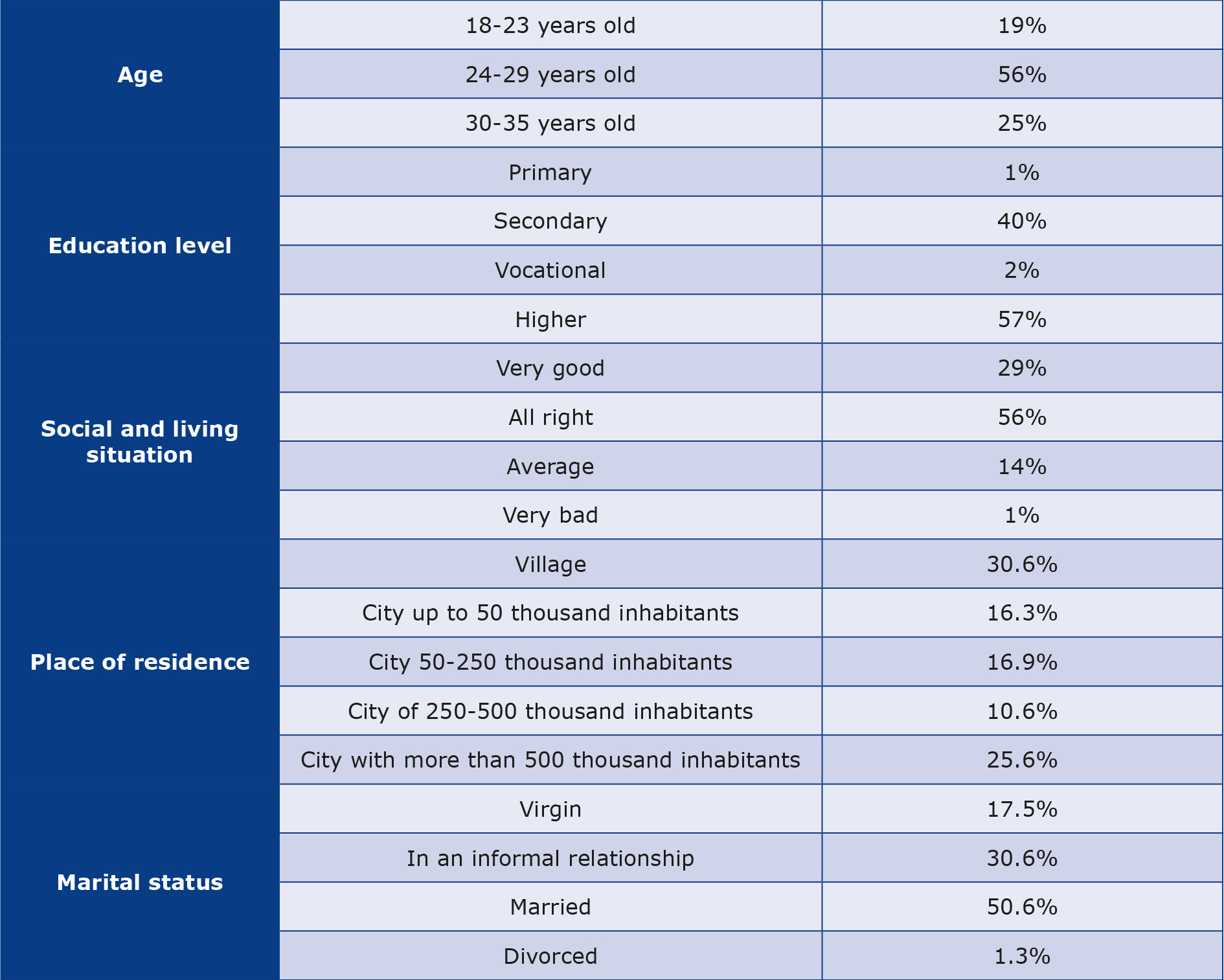

A total of 181 women participated in the study between July 2024 and February 2025. Responses of 21 participants were rejected due to meeting the age criteria of geriatric pregnancy (> 35 years of age) and teenage pregnancy (< 18 years of age) [19-20]. The study group consisted of 160 women: 50 of them were planning pregnancy, 52 were pregnant and 58 were after childbirth. The average age of the respondents was almost 27 years (M = 26.64), almost 57% (n = 91) of women had higher education, the majority of the respondents were married 50.6% (n = 81) and assessed their social and living situation as good – 56.25% (n = 90). 280 of all the participants experienced a miscarriage. In the group of 58 women after childbirth, 51.72% (n = 30) gave birth naturally, 31.04% (n = 18) gave birth by caesarean section, while 17.24% (n = 10) started labor naturally and ended it by caesarean section. The sense of attractiveness after childbirth changed in 65.52% of the respondents (n = 38). Only 13.79% (n = 8) of the respondents sought help from specialists when faced with difficulties related to sexual satisfaction. The detailed characteristics of the study group are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Socio-demographic data of the respondents

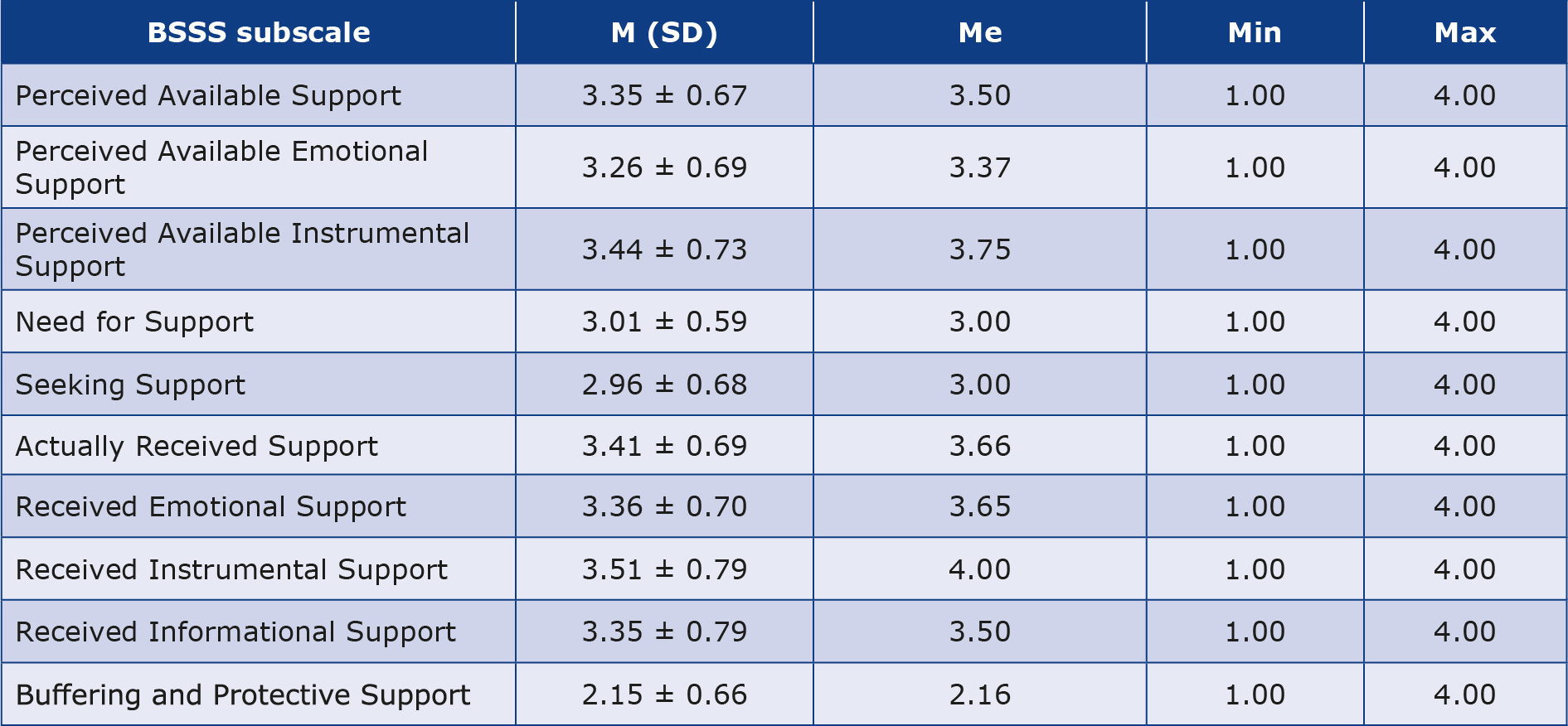

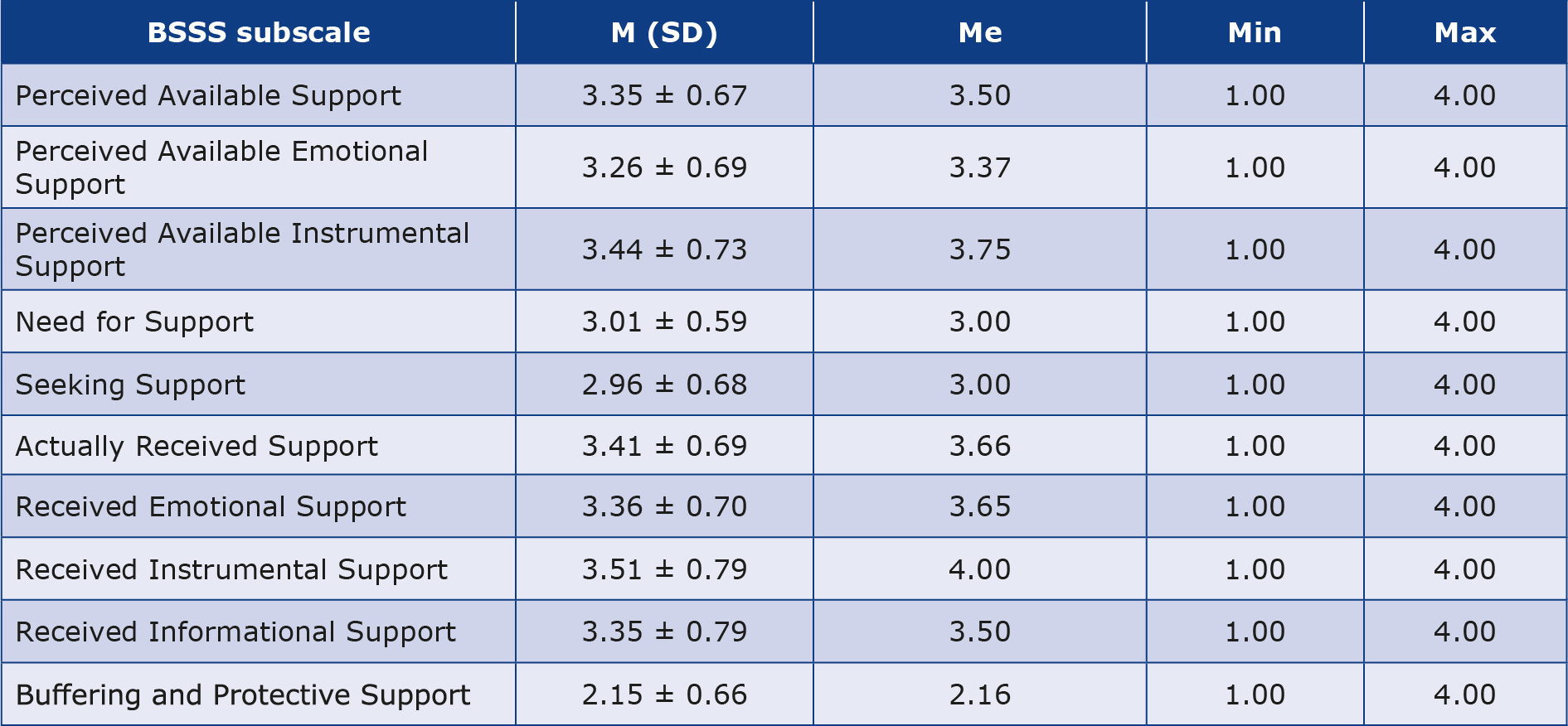

The highest average scores were obtained by the respondents in the subscale Actually Received Instrumental Support (3.51 ± 0.79), while the lowest values were recorded in the subscale Buffering and Protective Support (2.15 ± 0.66) (Table 2). The reliability of the subscales was as follows: Perceived Available Support (Cronbach’s α = 0.83), Need for Support (Cronbach’s α = 0.61), and Seeking Support (Cronbach’s α = 0.81) [20]. In our study, the overall reliability of the BSSS scale calculated based on the sum of items was Cronbach’s α = 0.89, which indicates high internal consistency in the analyzed sample. Higher values in our own study may result from the homogeneity of the studied sample.

Table 2. Basic statistics of the results obtained in the individual subscale Berlin Social Support Scale (BSSS) (n = 160)

M – mean; Max – the highest value of the distribution; Me – median; Min – the lowest value of the distribution; N – number; SD – standard deviation

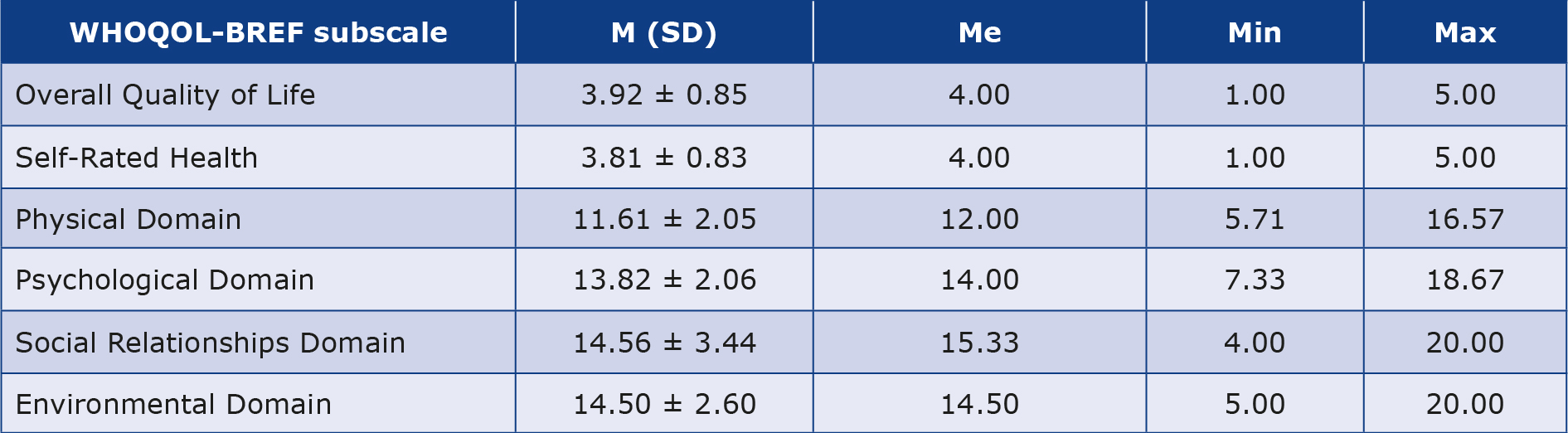

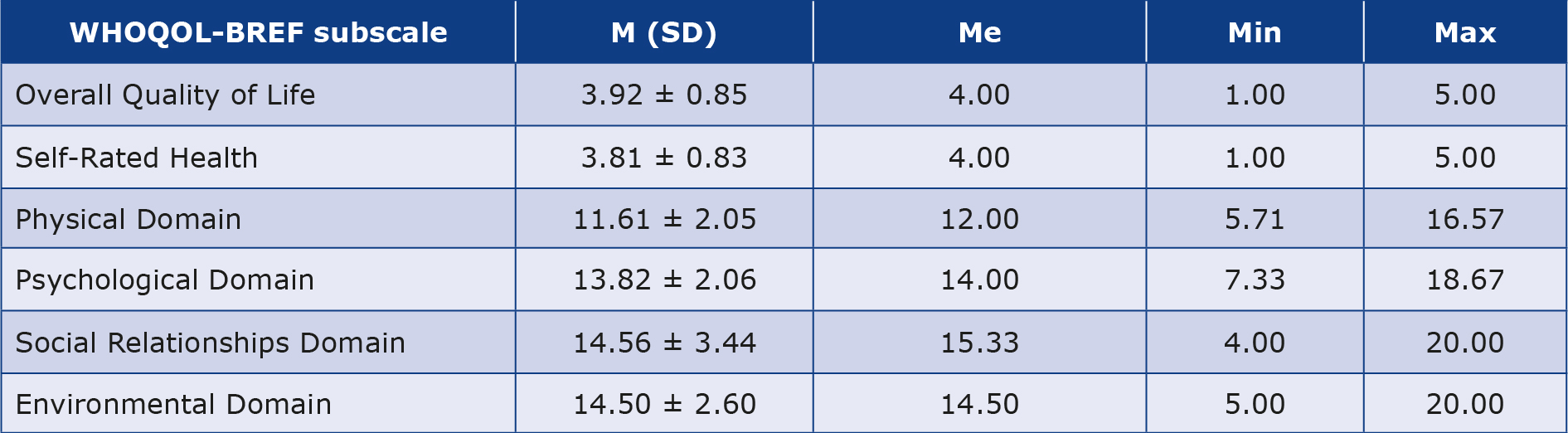

Using the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire, it was shown that the average Overall Quality of Life of the examined women was (3.92 ± 0.85). The average Self-Rated Health was slightly lower than the Overall Quality of Life and amounted to (3.81 ± 0.83). The participants assessed their QoL in the Physical Domain the lowest (11.61 ± 2.05), and the Social Relationship Domain the highest (14.56 ± 3.44). In the process of analyzing the results, it was assumed that the higher the number of points, the higher the level of QoL of the examined participants (Table 3). In our study, Cronbach’s α value was 0.93, which also indicates high internal consistency in the analyzed group.

Table 3. Basic statistics of the results obtained in the individual subscales of the WHOQOL-BREF (n = 160)

M – mean; Max – the highest value of the distribution; Me – median; Min – the lowest value of the distribution; N – number; SD – standard deviation

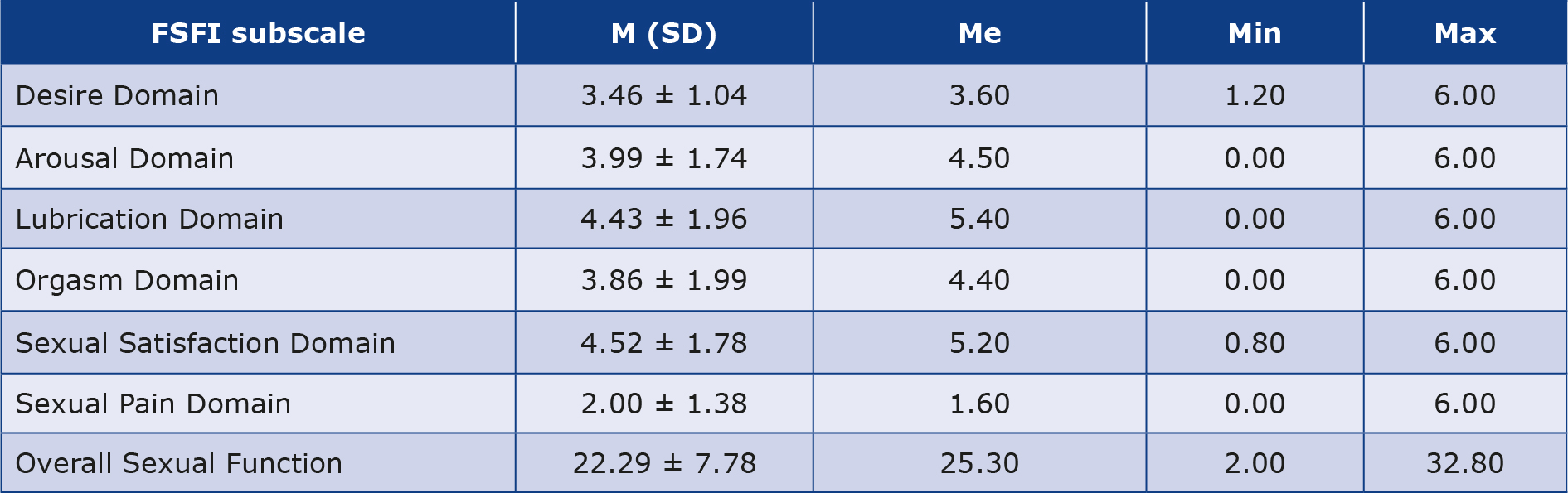

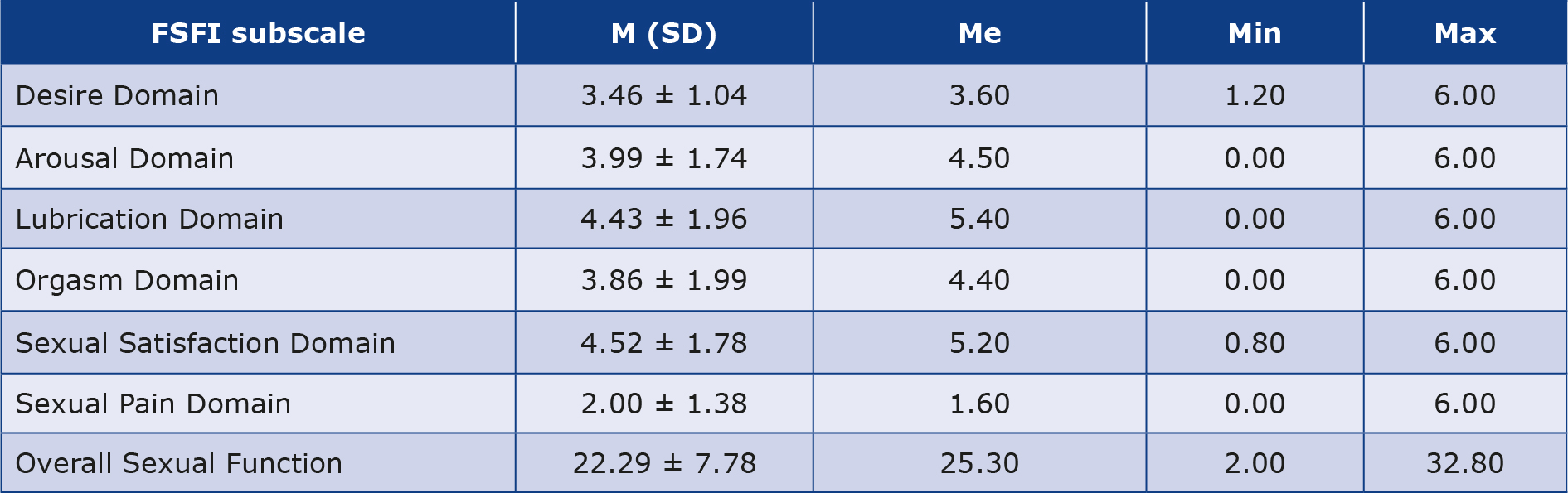

The results obtained on the FSFI scale are presented in Table 4. Taking into account the scale cut-off points of less than or equal to 26 points, sexual dysfunctions were found in almost 35% of the study participants (n = 55; 34.4%). On the Overall Sexual Function Scale, women obtained an average of 22.29 ± 7.78 points. The highest scores were obtained in the Sexual Satisfaction Domain (4.52 ± 1.78), while the lowest in the Sexual Pain Domain (2.00 ± 1.38) (Table 4). In our study, we obtained the coefficient α = 0.96, which confirms the high reliability of the tool in our sample of 160 Polish women.

Table 4. Basic statistics of the results obtained in the individual subscales of the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) (n = 160)

M – mean; Max – the highest value of the distribution; Me – median; Min – the lowest value of the distribution; N – number; SD – standard deviation

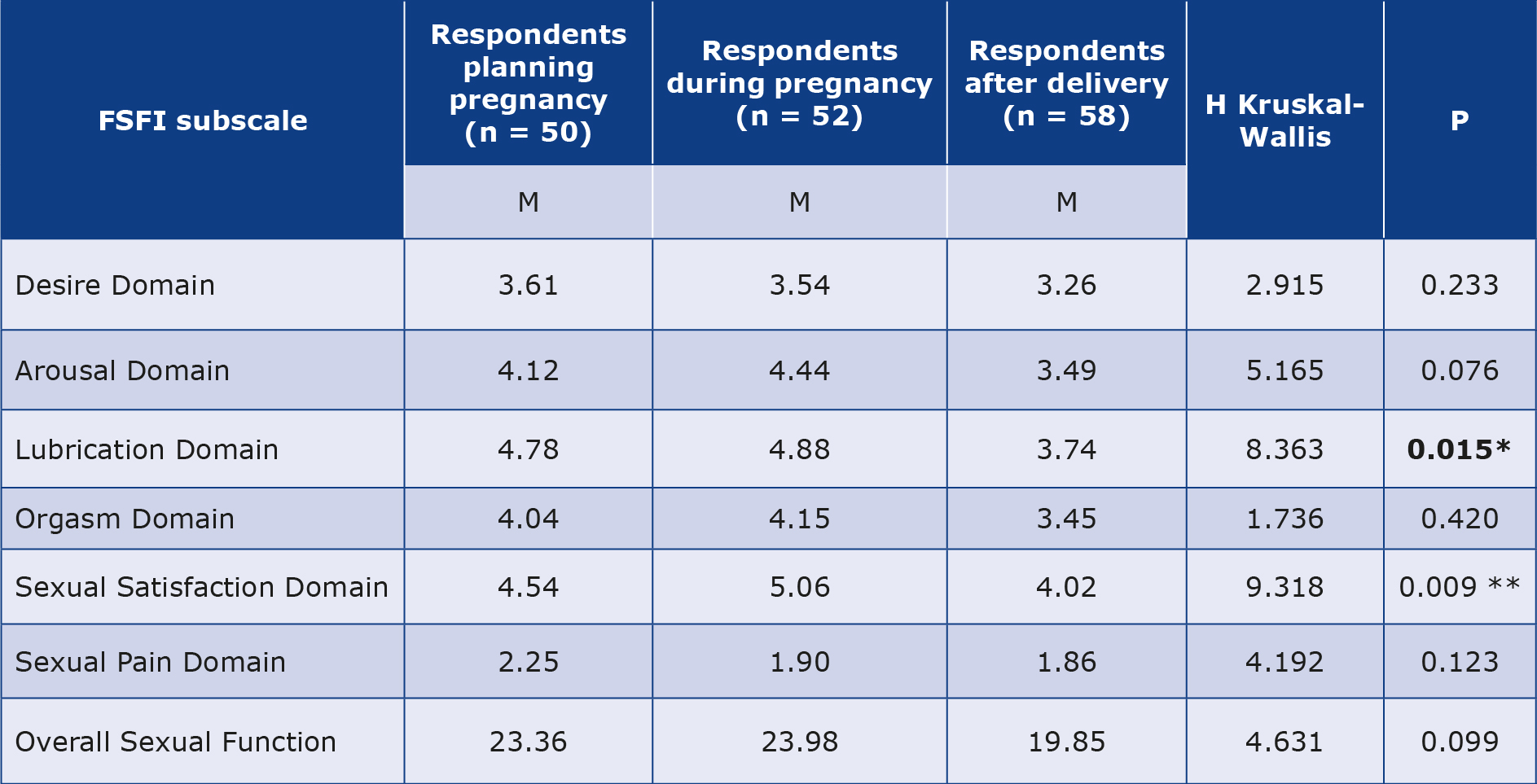

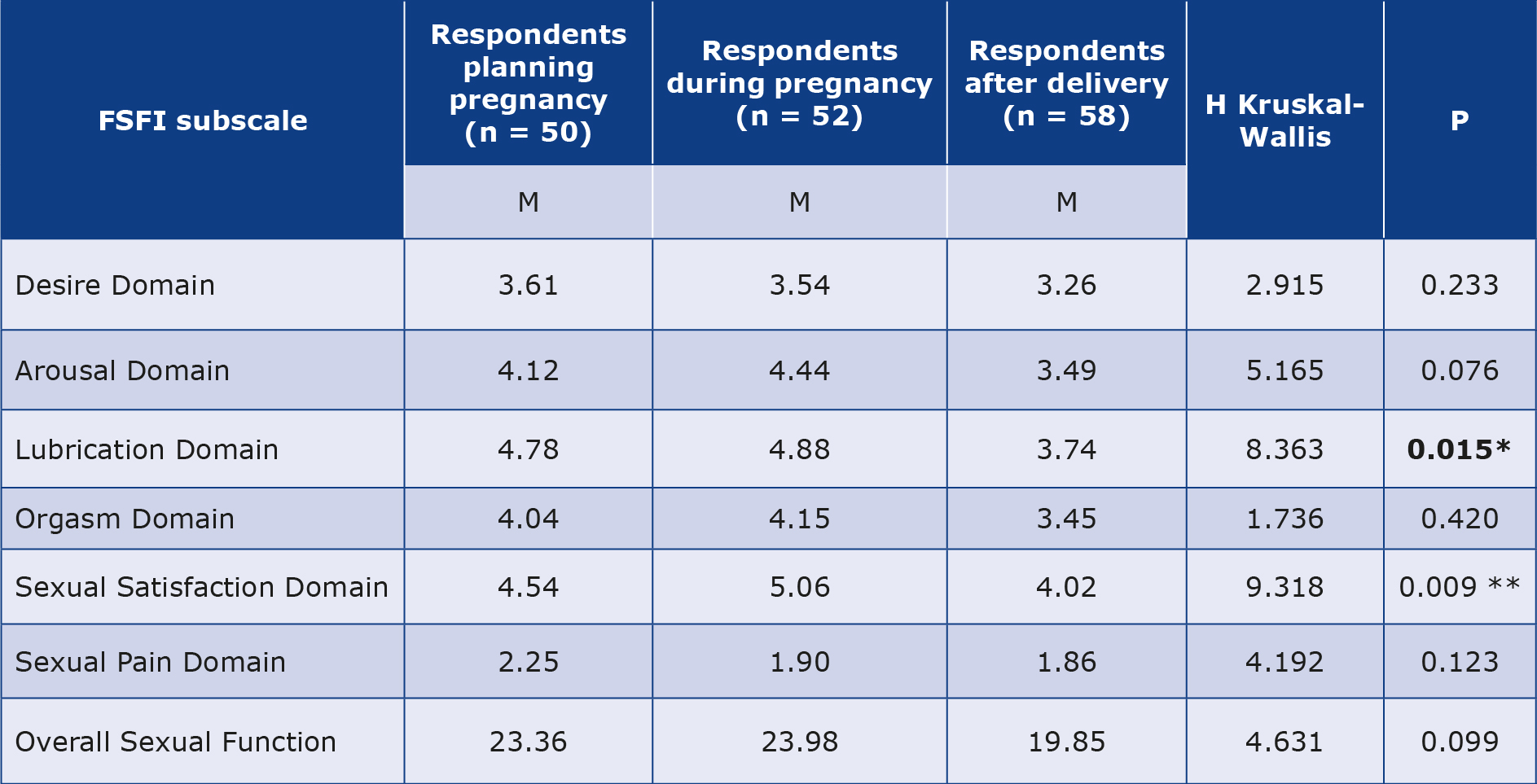

Our 1st hypothesis was that there are statistically significant differences between groups of women before pregnancy, during pregnancy and after childbirth in terms of social support, QoL and sexual functioning. Analysis of the obtained data showed statistically significant differences between the study participants in terms of the level of sexual functioning, including sexual satisfaction (p = 0.009). Pregnant women showed a higher level of sexual satisfaction (M = 5.06) compared to those planning a pregnancy (M = 4.54) and after childbirth (M = 4.02) (Table 5).

Table 5. Sexual functioning in the studied groups of women (n = 160)

* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 **

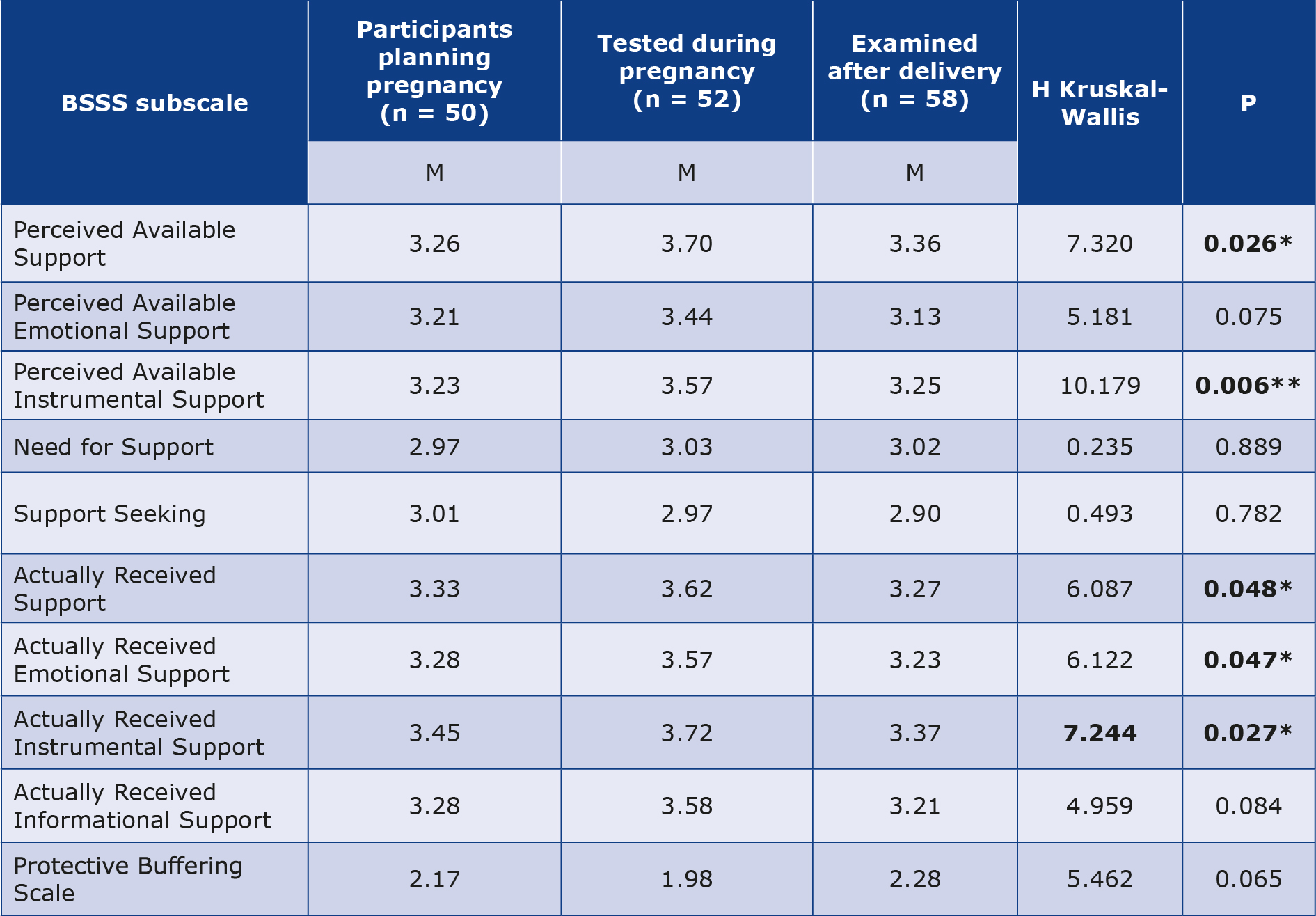

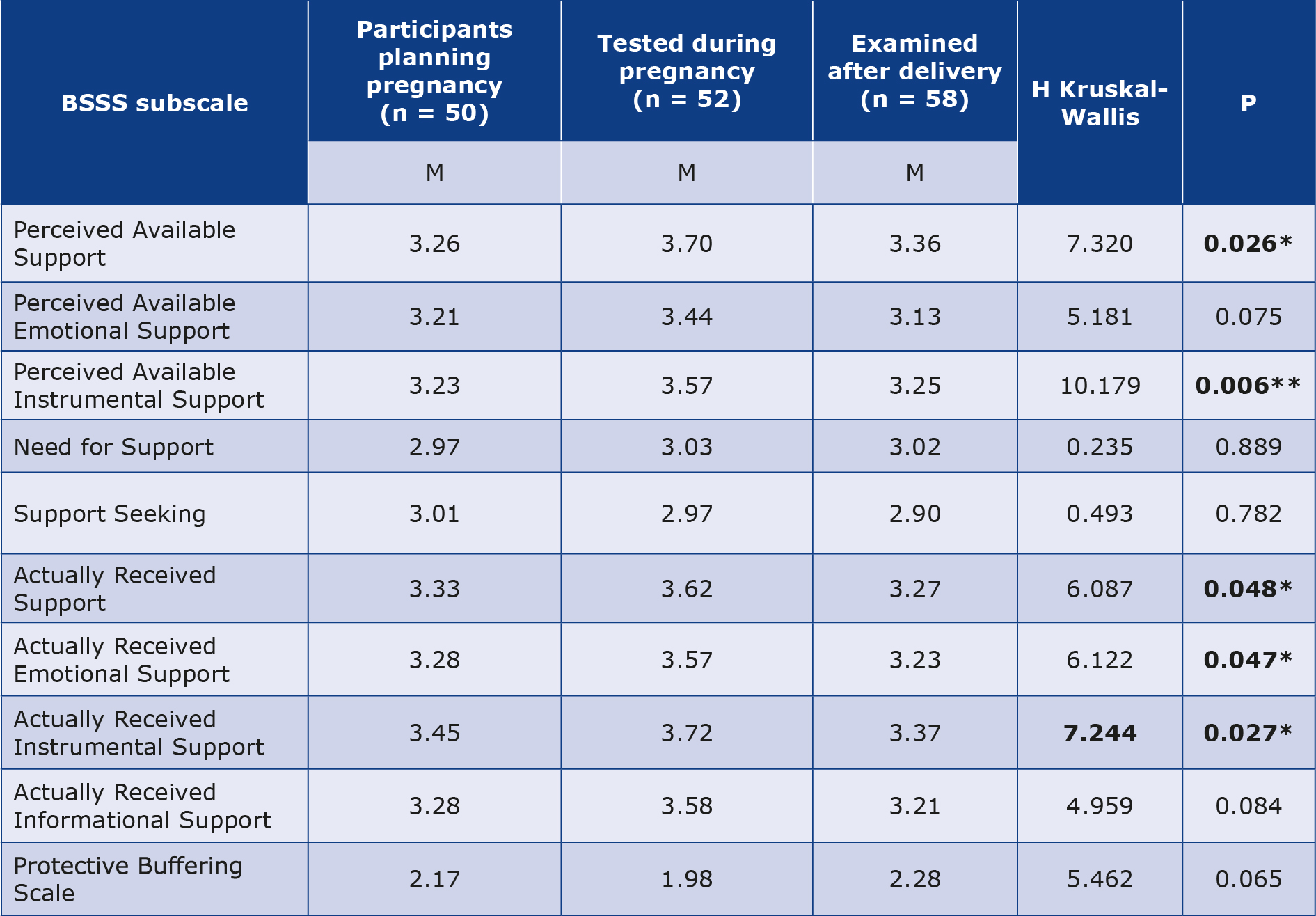

Analysis of the obtained data showed statistically significant differences between respondents in terms of the level of social support, including the Perceived Available Support, (p = 0.026), Perception Available Instrumental Support (p = 0.006), Actually Received Support (p = 0.048), Received Emotional Support (p = 0.047) and Instrumental Support (p = 0.027). Pregnant women showed higher levels of the indicated variables compared to women planning a pregnancy and those who had just given birth. It was shown that pregnant women (M = 3.70) had a higher mean in the subscale Perceived Available Support compared to the group of women after childbirth (M = 3.36) and those planning a pregnancy (M = 3.26). The group of women expecting a child also showed the highest mean (M = 3.57) among all the studied groups in the subscale Perceived Available Instrumental Support. Pregnant women (M = 3.62) also had higher scores on the subscale Actually Received Support compared to the other study groups. Pregnant women also achieved the highest mean scores (M = 3.57) on the Emotional Support Received subscale, compared to women planning a pregnancy (M = 3.28) and women after childbirth (M = 3.21), as well as in the subscale Received Instrumental Support (M = 3.72), whereas this result was M = 3.45 in women planning a pregnancy and M = 3.37 in women after childbirth. Detailed results regarding social support in the studied subgroups are presented in Table 6.

Table 6. Social support in the studied subgroups (n = 160)

* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 **

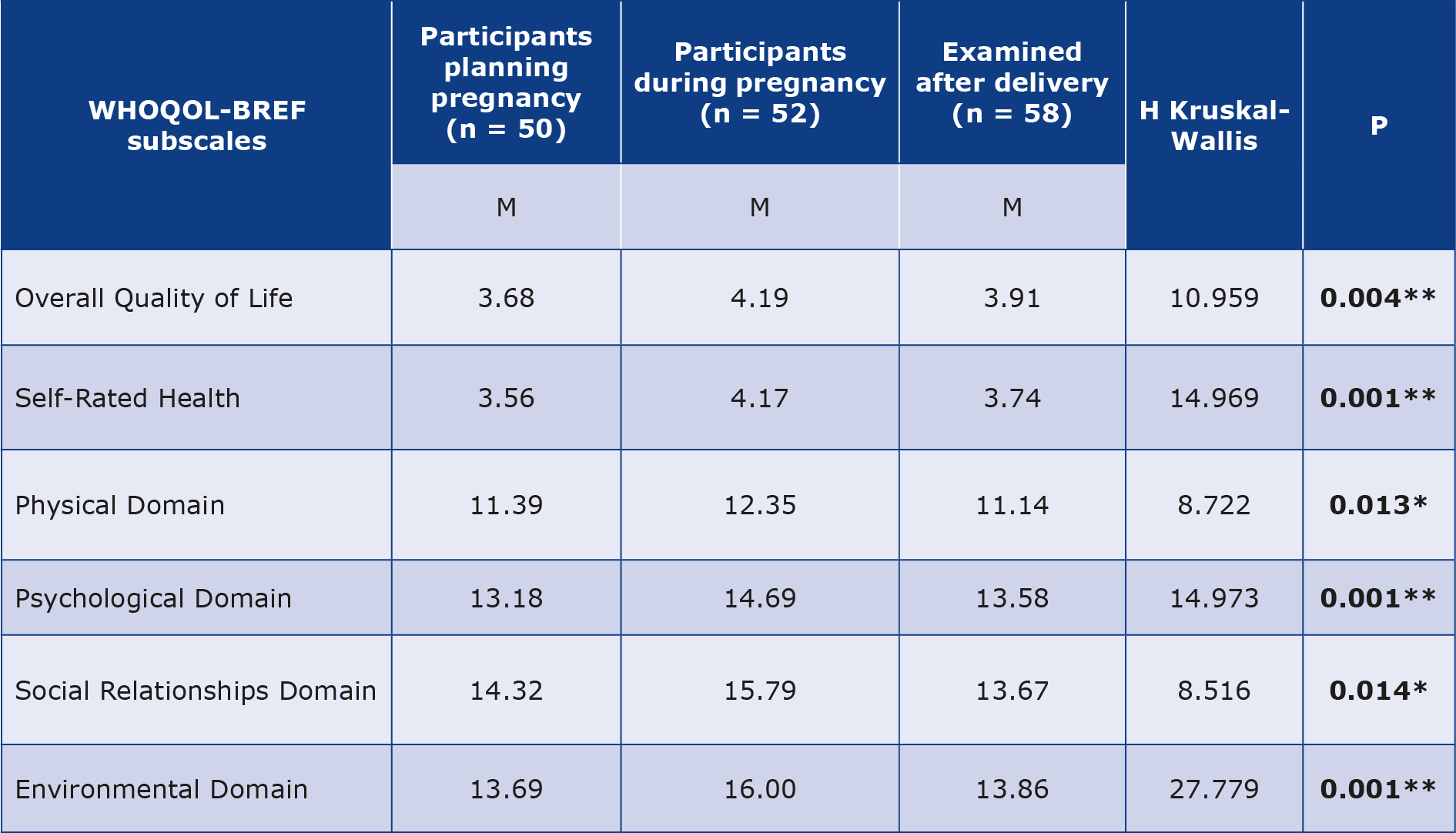

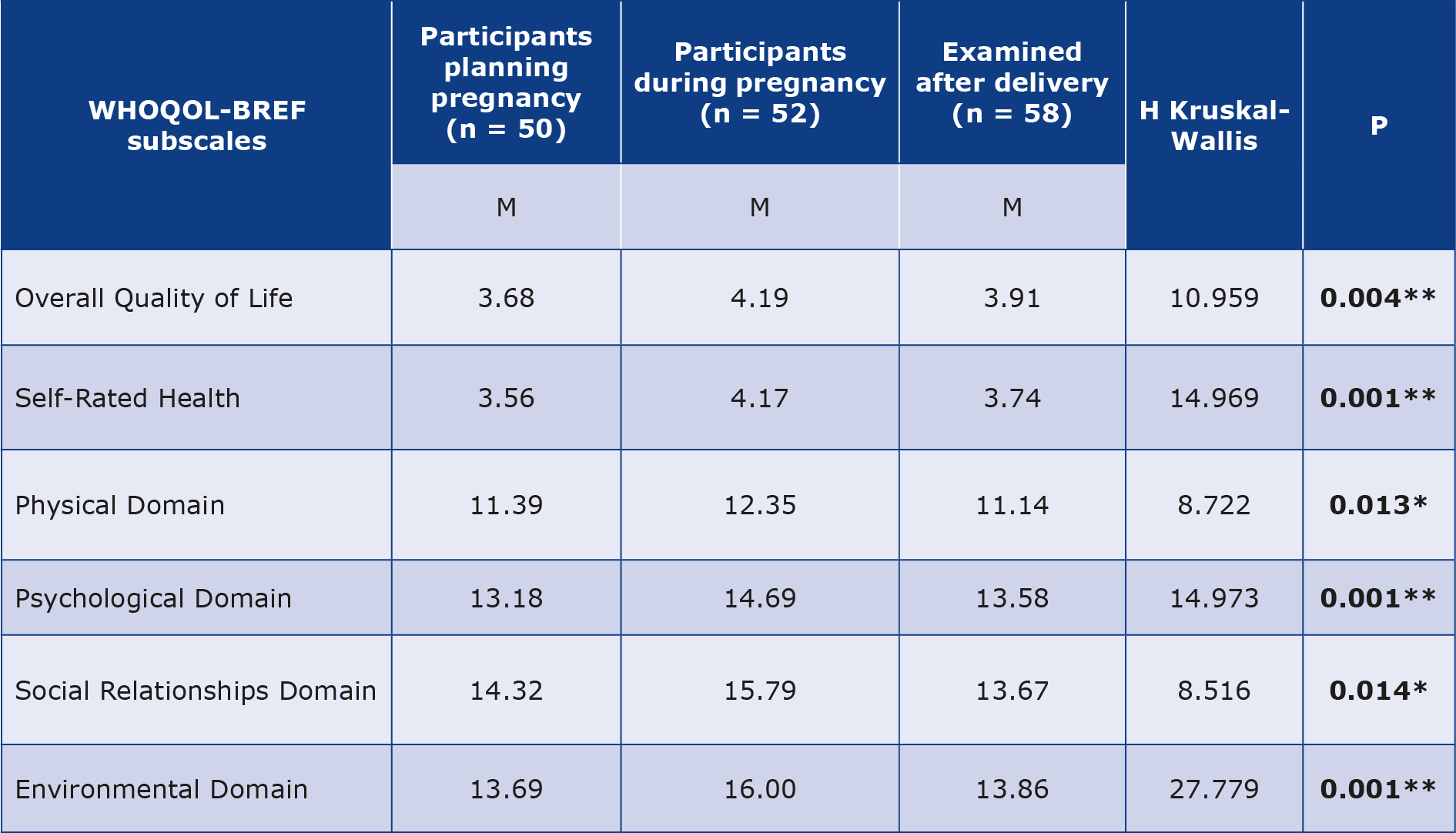

Statistically significant differences were found between the 3 study groups in terms of the level of QoL, including all its subscales: Overall Quality of Life (p = 0.004), Self-Rated Health Status (p = 0.001), Physical Domain (p = 0.013), Psychological Domain (p = 0.001), Social Relationships Domain (p = 0.014) and Environmental Domain (p = 0.001). Pregnant women showed higher QoL in all subscales compared to women planning a pregnancy and after childbirth (Table 7).

Table 7. Quality of life level with subscale WHOQOL-BREF in the study group (n = 160)

* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 **

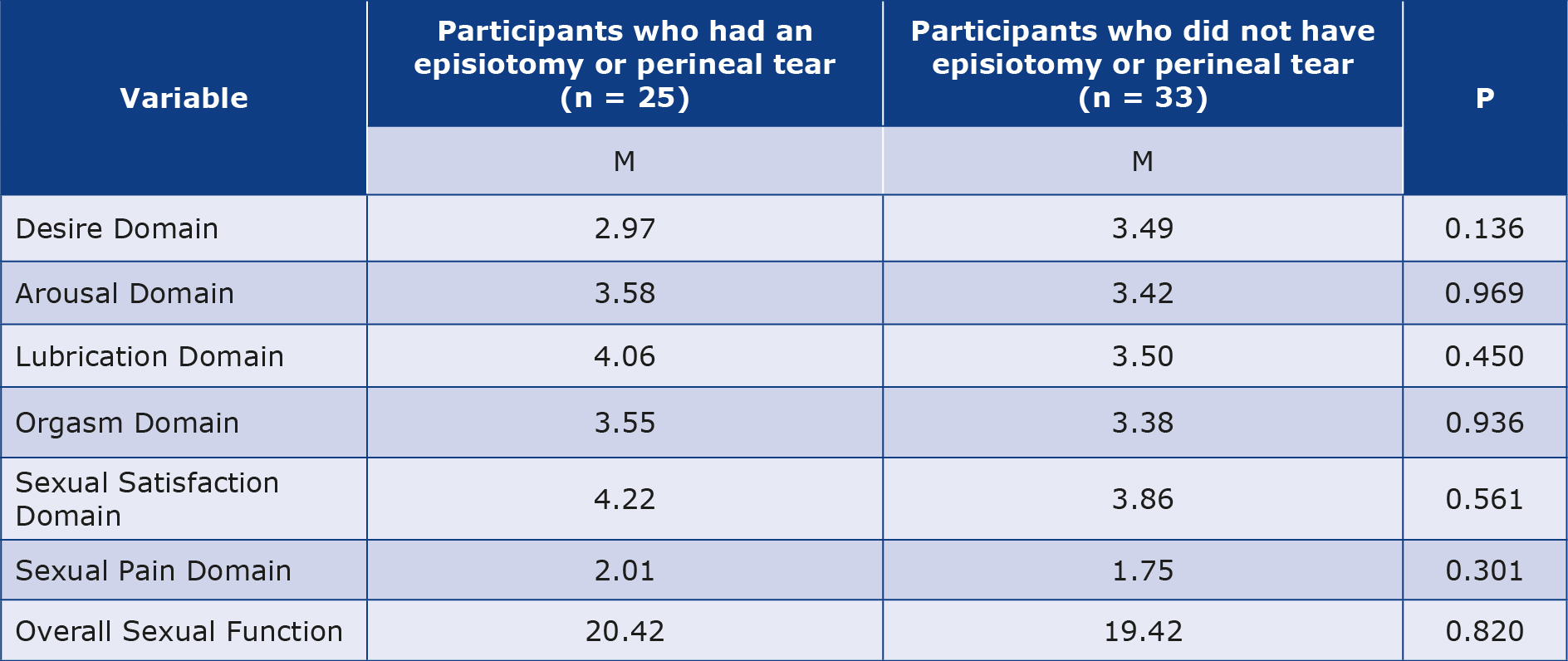

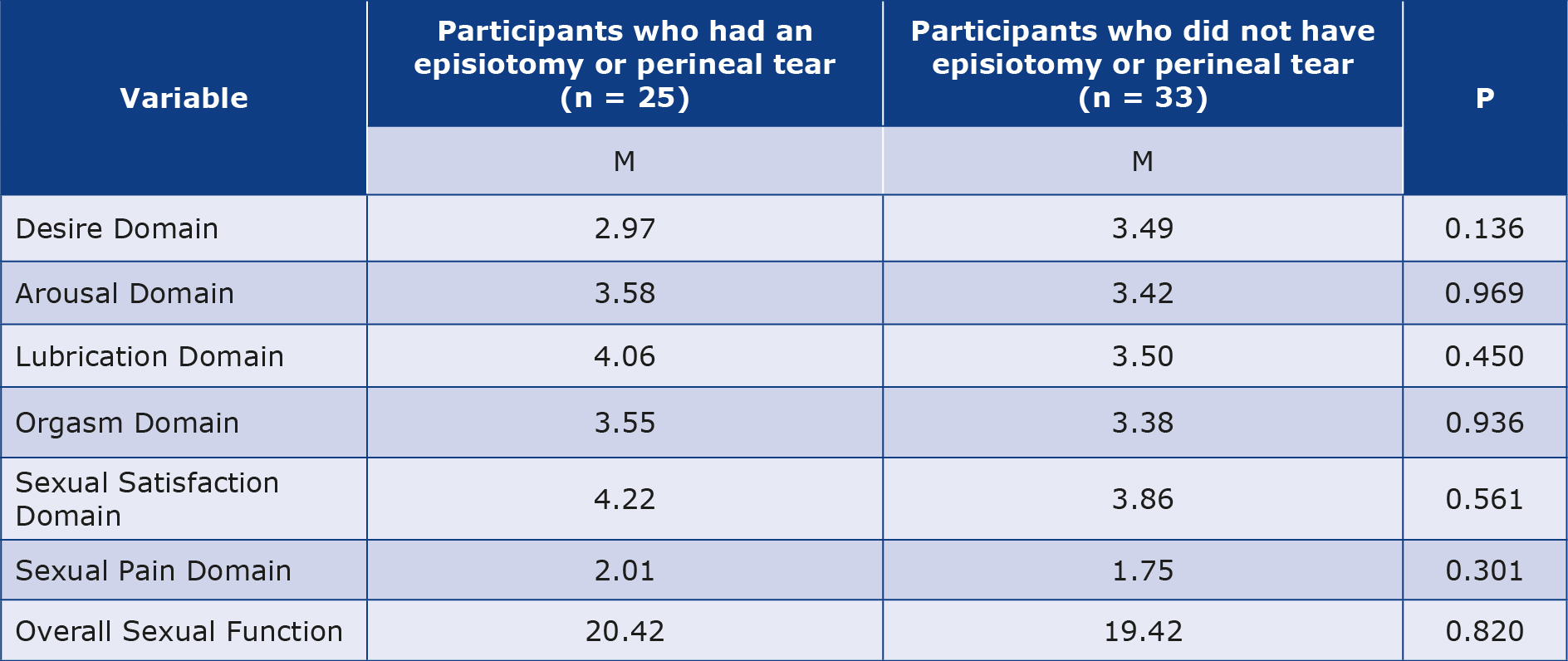

Our 2nd hypothesis was that episiotomy or laceration significantly affects the perception of the respondents’ sexuality. Statistical analysis was performed among postpartum women (n = 58), who were divided into two groups. The first group consisted of women who had experienced an incision or tear of the perineum (n = 25), while the second group did not experience any of the indicated situations (n = 33). There were no statistically significant differences between the studied groups in any of the domains assessing sexual functioning (Table 8).

Table 8. Perineal incision or laceration and sexual functioning of the studied women (n = 58)

* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 **

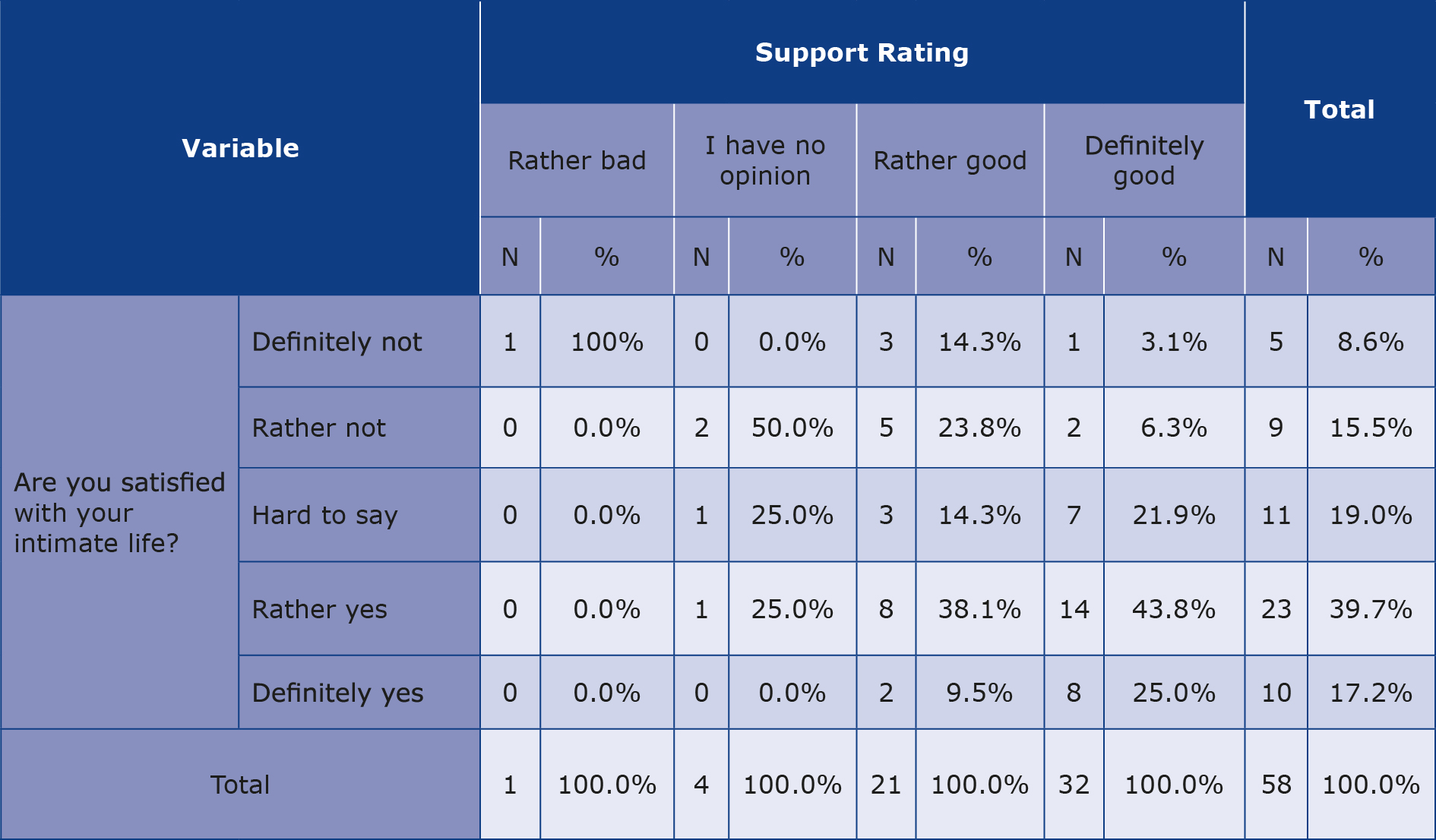

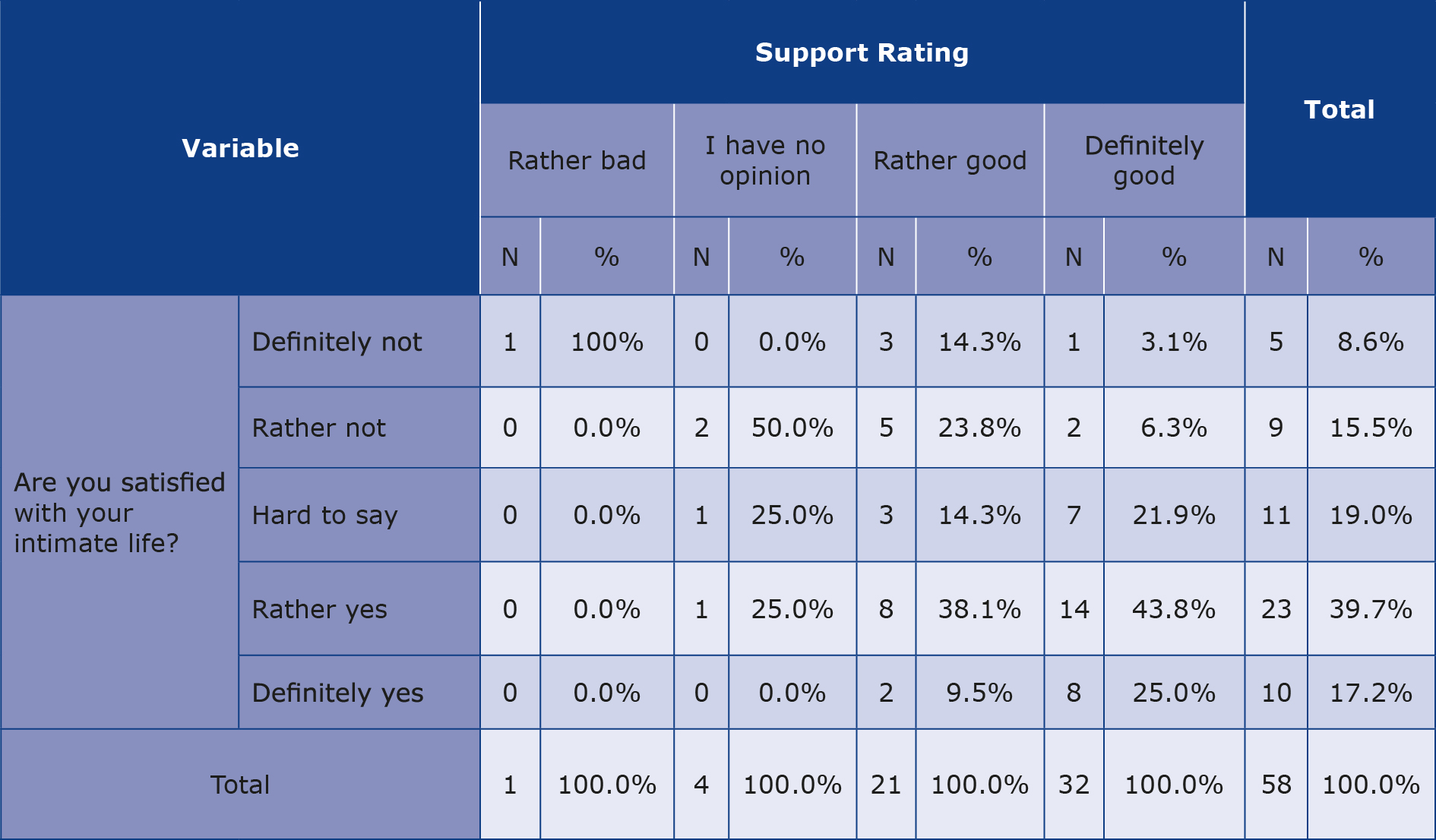

Our 3rd hypothesis was that support from loved ones is associated with higher levels of sexual satisfaction. The chisquare test result showed a statistically significant relationship between support from close ones and satisfaction with intimate life (χ2 = 21.974, p = 0.038). Women who rated their intimate life as “good” were more likely to rate support from close ones as definitely good compared to other levels of satisfaction with intimate life (Table 9).

Table 9. Support from close ones and satisfaction with intimate life in the study group – chi-square test (n = 58)

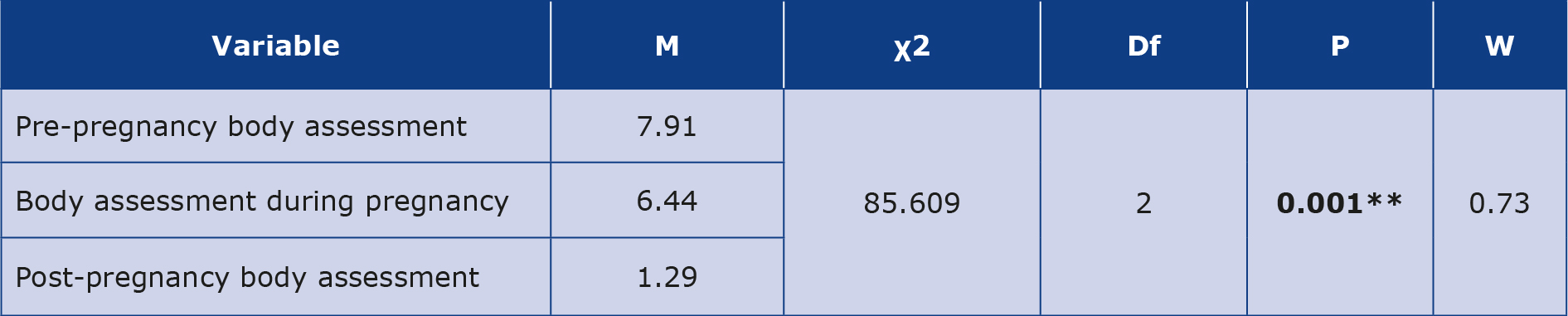

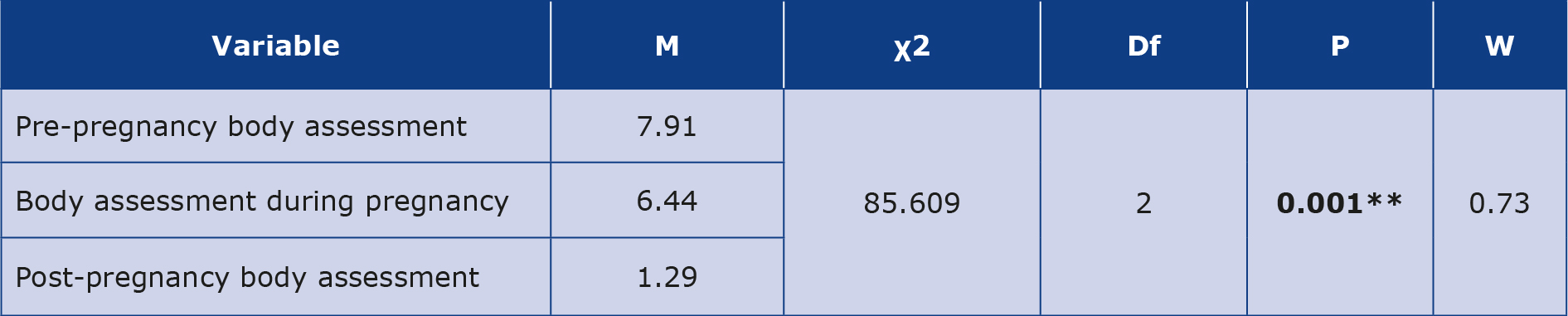

The analysis of differences in the assessment of the body before, during and after childbirth among the respondents showed statistically significant differences (p = 0.001). The surveyed women assessed their bodies better before pregnancy (M = 7.91) than during pregnancy and after childbirth (M = 1.29). The effect of the strength of the relationship between variables is strong (r = 0.73) (Table 10).

Table 10. Body assessment before pregnancy, during pregnancy and after delivery in the studied subgroups

χ2 – Friedman test; df – degrees of freedom; M –mean, W – Kendal’s W; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01** **

In order to identify variables that best predict women’s level of sexual satisfaction (FSFI), we conducted multiple regression analysis taking into account clinical factors such as episiotomy, type of delivery, change in sexual feelings after childbirth, sense of attractiveness and the level of social support measured by the BSSS. The regression model was statistically significant (p < 0.001) and its fit was estimated at R² = 0.29, which means that it explains 29% of the variance in the level of sexual satisfaction. Among the clinical variables, type of delivery (p = 0.090) and change in sexual sensations after delivery (p = 0.090) approached statistical significance, indicating the potential importance of these factors in reducing sexual satisfaction.

Discussion

The reproductive period is a special time for women, during which a number of physical and mental changes occur. Research from 2023 conducted in 32 countries by the Ipsos Group showed that only 63% of all respondents declared satisfaction with their sexual life, with the highest percentage result recorded in China (79%), while in Poland this result amounted to 60% of respondents [21].

The analyzed study indicates the need to deepen knowledge in this area, identify factors influencing this condition and find ways to improve it. There is widely believed in the society that sexual satisfaction after childbirth can be influenced and reduced by an incision or tearing of the perineum. However, we did not find statistically significant results that would confirm this thesis. The conducted multiple regression analysis showed that the type of delivery and the subjective change in sexual feelings after childbirth may be factors influencing the decrease in sexual function. Despite the lack of significance of individual scale items (BSSS), the inclusion of social support in the regression model increased its explanatory power, suggesting that the overall relational and emotional climate may play an important role in women’s sexual well-being.

In a 2018 study conducted by O’Malley et al., 46.3% of postpartum women reported a lack of interest in sexual activity, which was influenced by: dyspareunia (37.5%, understood as pain before, during or after intercourse), lack of lubrication and dissatisfaction with the appearance of their own body [22]. In this study, women asked about changes in their sexual life during pregnancy declared: both decreased and increased libido, less freedom of movement, a limited number of sexual positions and increased body sensitivity. The greatest difficulties in sexual life during pregnancy among the respondents were: general fatigue, nausea, back pain, swollen legs, the size of the belly that makes it difficult to move freely and problems with choosing a sexual position. When asked about changes and the greatest difficulties in sexual life after pregnancy, respondents declared: pain during intercourse, low satisfaction with appearance after childbirth, general fatigue and lack of desire for sex. The available review study from 2024 confirms a decrease in sexual drive after childbirth, an increase in perineal pain and dyspareunia, as well as a lower intensity and shorter duration of orgasm in the first 3 months after childbirth [23]. It is worth emphasizing that numerous studies indicate a strong relationship between social support and the level of sexual satisfaction. The role of the positive influence of support from close people, a good relationship with the partner and a stable emotional state are emphasized, as well as their importance in the context of the perceived sexual satisfaction, which was also confirmed in the conducted study [24-26].

Scientific research also indicates a high need for social support among women during pregnancy and after childbirth. In a cross-sectional study conducted in 2024 Nazzal et al. showed that there is a positive, statistically significant relationship (p < 0.05) between social support and the level of QoL, which is consistent with our results. Pregnant women experience greater social support than women before pregnancy and after childbirth [27]. The same results were obtained by Emmanuel et al., showing that social support is a significant and consistent predictor of higher health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in women in the perinatal period [28]. Gebuze et al. showed that social support is a significant factor influencing life satisfaction in pregnant Polish women and after childbirth. Women who received greater social support reported a higher level of life satisfaction [7]. Zhou et al. obtained different results in their study: the surveyed women declared a reduced sense of social support during pregnancy and perinatal period. The COVID-19 pandemic that took place at that time could have had a significant impact on various results, through the restrictions and the resulting reduction in social contacts contributed to a significant deterioration in the mental state of women [29]. In addition, Faleschini et al. demonstrated that support received from a partner and family has a positive effect on a woman, which is a protective factor against postpartum depression and translates into increased physical activity and maintaining healthier eating habits, which in turn prevents obesity [30].

Our results showed that pregnant women assess their QoL higher and their overall health better compared to other groups. This may be influenced by the perception of pregnancy as a special period in a woman’s life. Despite the accompanying physical ailments, women experience increased care from their environment during this time and are more motivated to lead a healthy lifestyle. A healthy diet, adequate sleep and avoiding stimulants are factors that can influence a better self-assessment of their condition. The obtained results are consistent with the Iranian study by Mortazavi et al., which showed that women’s QoL increases in the third trimester of pregnancy, mainly in the psychological and social sphere, which according to the authors is strongly related to greater support from loved ones and preparations for childbirth. In turn, after childbirth, the QoL often deteriorates, especially in the first months, when women struggle with physical exhaustion, hormonal changes and lack of sleep/time for regeneration [31].

Our results indicate that women evaluate their bodies much better before pregnancy than during pregnancy and after childbirth. These differences are statistically highly significant and confirm the observations from previous studies, which show the impact of physical and psychological changes related to pregnancy and motherhood on the perception of one’s own body. A number of hormonal and anatomical changes occur in a woman’s body during pregnancy, e.g. body weight increases, body posture changes, swelling and stretch marks appear. Although these changes are physiological and natural, women often find it difficult to come to terms with the loss of their pre-pregnancy image, which is associated with a lower mood and lack of acceptance of their own body [10, 32].

Limitations of this study

Our study group involved 160 women and due to its size it might not reflect trends in the greater population. In addition, the study was made available only online on websites dedicated for women who were either planning to have a child, were pregnant or were postpartum. The women were at different stages of declared pregnancy, which could also have influenced the answers provided and the results obtained. Another limitation of the study is the lack of measurement of depressive symptoms, which are common in the perinatal period and could affect the level of sexual satisfaction. In the future, it is worth including this variable as a control. Despite the obtained results indicating certain tendencies in the study group, the researchers point to the justification for continuing the conducted research. There is a need to increase the sample size, as well as further explore the discussed issues, taking into account additional variables (e.g. the aforementioned depressive symptoms).

Conclusions

1. Pregnant women experience higher levels of sexual satisfaction compared to women before and after pregnancy.

2. The surveyed pregnant women showed higher levels of perceived available support (instrumental support dimension) and received support (emotional and instrumental support dimension) compared to women planning a pregnancy and after childbirth.

3. Pregnant women assess their health, mental health, social relationships and overall QoL higher than other studied groups.

4. Medical intervention in the form of vaginal incision or laceration during childbirth has no effect on a woman’s sexual functioning (the correlations were not statistically significant).

5. Women who rated their intimate life as good were more likely to rate the support of loved ones as definitely good, compared to women with other levels of satisfaction with intimate life.

6. The surveyed women rated their bodies significantly higher before pregnancy than during pregnancy and after childbirth. Changes in appearance can be a challenge on the path to motherhood. It is reasonable to support women in accepting their bodies through social support and education on the physiological changes that occur in a woman during pregnancy and after childbirth.

7. Both physical factors (e.g. mode of delivery) and psychosocial factors (e.g. perception of sexual sensations, social support) should be taken into account in perinatal care and in educational activities (e.g. childbirth classes) aimed at women and their partners.

8. More research is needed in orther to further explore the above-mentioned issues and to include new variables (e.g. symptoms of depression).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank each woman who participated in this study.

Funding

This work was not financed by any scientific research institution, association or other entity and the authors did not receive any grant.

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

| 1. |

Education and treatment in human sexuality : the training of health professionals, report of a WHO meeting [held in Geneva from 6 to 12 February 1974] [Internet]. Worth Health Organization. [cited 2025 Jun 30]. Available from: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/38247.

|

| 2. |

Rudolf E. Zdrowie reprodukcyjne kobiet – rozważania terminologiczne [in Polish]. In: Problemy zdrowia reprodukcyjnego kobiet Wstęp do badań [Internet]. 2016. p. 19–36. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/312220204_Zdrowie_reprodukte_kobiet__rozwazania_terminologiczne.

|

| 3. |

Grussu P, Vicini B, Quatraro RM. Sexuality in the perinatal period: A systematic review of reviews and recommendations for practice. Sex Reprod Healthc [Internet]. 2021;30:100668. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1877575621000756.

|

| 4. |

Narodowy raport o seksualności 2024 [in Polish] [Internet]. Medycyna Praktyczna. 2024 [cited 2025 Jun 30]. Available from: https://www.mp.pl/kurier/349008,narodowy-raport-o-seksualnosci-2024.

|

| 5. |

Fuchs A, Czech I, Dulska A, Drosdzol-Cop A. The impact of motherhood on sexuality. Ginekol Pol [Internet]. 2021;92(1):1–6. Available from: https://journals.viamedica.pl/ginekologia_polska/article/view/68189.

|

| 6. |

Zgliczynska M, Zasztowt‐Sternicka M, Kosinska‐Kaczynska K, Szymusik I, Pazdzior D, Durmaj A, et al. Impact of childbirth on women’s sexuality in the first year after the delivery. J Obstet Gynaecol Res [Internet]. 2021;47(3):882–92. Available from: https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jog.14583.

|

| 7. |

Gebuza G, Kaźmierczak M, Mieczkowska E, Gierszewska M. Wsparcie społeczne jako determinant zadowolenia z życia u kobiet w okresie ciąży i po cięciu cesarskim [in Polish]. Psychiatr Pol [Internet]. 2018;52(3):598–885. Available from: https://www.psychiatriapolska.pl/Social-support-as-a-determinant-of-life-satisfaction-inpregnant-women-and-women,64194,0,1.html.

|

| 8. |

Ilska M, Przybyła-Basista H, Ilski A, Cnota W. Aktywność i satysfakcja seksualna kobiet w ciąży prawidłowej oraz wysokiego ryzyka [in Polish]. Ginekol Poloz [Internet]. 2018;2:34–41. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/338358100_Aktywnosc_i_spokojcja_seksualna_kobiet_w_ciazy_prawidlowej_oraz_wysokiego_ryzyka.

|

| 9. |

Makara-Studzińska M, Wdowiak A, Plewik I. Seksualność kobiet w ciąży [in Polish]. Seksuologia Pol [Internet]. 2011;9(2):85–90. Available from: https://ruj.uj.edu.pl/entities/publication/d46f4ae4-28f5-4291-8437-851ae788da42.

|

| 10. |

Duncombe D, Wertheim EH, Skouteris H, Paxton SJ, Kelly L. How Well Do Women Adapt to Changes in Their Body Size and Shape across the Course of Pregnancy? J Health Psychol [Internet]. 2008;13(4):503–15. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1359105308088521.

|

| 11. |

McDonald E, Woolhouse H, Brown SJ. Sexual pleasure and emotional satisfaction in the first 18 months after childbirth. Midwifery [Internet]. 2017;55:60–6. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0266613817300864.

|

| 12. |

Khawaja M, Habib RR. Husbands’ Involvement in Housework and Women’s Psychosocial Health: Findings From a Population-Based Study in Lebanon. Am J Public Health [Internet]. 2007;97(5):860–6. Available from: https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/full/10.2105/AJPH.2005.080374.

|

| 13. |

Hogan JN, Crenshaw AO, Baucom KJW, Baucom BRW. Time Spent Together in Intimate Relationships: Implications for Relationship Functioning. Contemp Fam Ther [Internet]. 2021;43(3):226–33. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34334944.

|

| 14. |

Fanshawe A-M, De Jonge A, Ginter N, Takács L, Dahlen HG, Swertz MA, et al. The Impact of Mode of Birth, and Episiotomy, on Postpartum Sexual Function in the Medium- and Longer-Term: An Integrative Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2023;20(7):5252. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/20/7/5252.

|

| 15. |

Leal IMP, Lourenço S, Oliveira R, Carvalheira A, Maroco J. Sexual function in women after delivery: Does episiotomy matter? Health (Irvine Calif) [Internet]. 2014;6(05):356–63. Available from: https://www.scirp.org/journal/papercitationdetails?paperid=43131&journalid=65.

|

| 16. |

THE WHOQOL GROUP. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF Quality of Life Assessment. Psychol Med [Internet]. 1998;28(3):551–8. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/S0033291798006667/type/journal_article.

|

| 17. |

Rosen, C. Brown, J. Heiman, S. Leib R. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A Multidimensional Self-Report Instrument for the Assessment of Female Sexual Function. J Sex Marital Ther [Internet]. 2000;26(2):191–208. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/009262300278597.

|

| 18. |

Łuszczyńska A, Kowalska M, Schulz U, Schwarzer R. Berlin Social Support Scales (BSSS) - Polish Version [Internet]. 2002 [cited 2025 Jun 30]. Available from: https://userpage.fu-berlin.de/~health/soc_pol.htm.

|

| 19. |

Frankowicz-Gasiul B, Michalik A, Czerwińska A, Zydorek M, Olszewska J, Olszewski J. Ciąża młodocianych – problem medyczny i społeczny [in Polish]. Stud Med [Internet]. 2008;11:57–63. Available from: https://studiamedyczne.ujk.edu.pl/doc/SM_tom_11/Ciaza mlodocianych.pdf.

|

| 20. |

Erasmus E. Pregnancy After 35: Why Science Says It’s Safe. [Internet]. Parents. [cited 2025 Jun 30]. Available from: https://www.parents.com/getting-pregnant/age/pregnancyafter-35/psa-its-totally-fine-to-have-babies-after-35-science-backs/.

|

| 21. |

Stinson J. Love life satisfaction around the world. A 30-Country Global Advisor Survey [Internet]. 2025. Available from: https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/news/documents/2025-02/ipsos-love-life-satisfaction-index-2025_0.pdf.

|

| 22. |

O’Malley D, Higgins A, Begley C, Daly D, Smith V. Prevalence of and risk factors associated with sexual health issues in primiparous women at 6 and 12 months postpartum; a longitudinal prospective cohort study (the MAMMI study). BMC Pregnancy Childbirth [Internet]. 2018;18(1):196. Available from: https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12884-018-1838-6.

|

| 23. |

Rezaei N, Behboodi Moghadam Z, Tahmasebi A, Taheri S, Namazi M. Women`s sexual function during the postpartum period: A systematic review on measurement tools. Medicine (Baltimore) [Internet]. 2024;103(30):e38975. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/10.1097/MD.0000000000038975.

|

| 24. |

Leeman LM, Rogers RG. Sex After Childbirth. Obstet Gynecol [Internet]. 2012 Mar;119(3):647–55. Available from: http://journals.lww.com/00006250-201203000-00024.

|

| 25. |

Kardasz Z, Szymańska J. Poziom stresu pourazowego, poczucia satysfakcji z życia i satysfakcji seksualnej po porodzie naturalnym, z asystą osoby towarzyszącej i bez niej [in Polish]. Fam Forum [Internet]. 2024 Dec 20;14:267–87. Available from: https://czasopisma.uni.opole.pl/index.php/ff/article/view/5088.

|

| 26. |

Stadnicka G, Łepecka-Klusek C, Pilewska-Kozak AB, Pawłowska-Muc AK. Satysfakcja seksualna kobiet po porodzie — część I [in Polish]. Probl Pielęgniarstwa [Internet]. 2015;23(3):357–61. Available from: https://www.termedia.pl/Journal/-134/pdf-35585-1.

|

| 27. |

Nazzal S, Ayed A, Zaben KJ, Abu Ejheisheh M, ALBashtawy M, Batran A. The Relationship Between Quality of Life and Social Support Among Pregnant Women: A Cross-Sectional Study. SAGE Open Nurs [Internet]. 2024 Jan 5;10. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/23779608241301225.

|

| 28. |

Emmanuel E, St John W, Sun J. Relationship between Social Support and Quality of Life in Childbearing Women during the Perinatal Period. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs [Internet]. 2012 Nov;41(6):E62–70. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0884217515312296.

|

| 29. |

Zhou J, Havens KL, Starnes CP, Pickering TA, Brito NH, Hendrix CL, et al. Changes in social support of pregnant and postnatal mothers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Midwifery [Internet]. 2021;103:103162. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0266613821002424.

|

| 30. |

Faleschini S, Millar L, Rifas-Shiman SL, Skouteris H, Hivert M-F, Oken E. Women’s perceived social support: associations with postpartum weight retention, health behaviors and depressive symptoms. BMC Womens Health [Internet]. 2019;19(1):143. Available from: https://bmcwomenshealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12905-019-0839-6.

|

| 31. |

Mortazavi F, Mousavi SA, Chaman R, Khosravi A. Maternal Quality of Life During the Transition to Motherhood. Iran Red Crescent Med J [Internet]. 2014 May 5;16(5). Available from: https://archive.ircmj.com/article/16/5/15924-pdf.pdf.

|

| 32. |

Clark A, Skouteris H, Wertheim EH, Paxton SJ, Milgrom J. The Relationship between Depression and Body Dissatisfaction across Pregnancy and the Postpartum. J Health Psychol [Internet]. 2009;14(1):27–35. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1359105308097940.

|