Abstract

Background: the process of treating infertility using the in vitro method can affect both physical and mental health. The study aims to determine the impact of trying to conceive using the in vitro method on the quality of life and psychological well-being of women.

Material and methods: respondents completed an online questionnaire. The experiment was conducted from July to December 2023 and 100 women involved. It was based on an questionnaire created by the authors and questionnaire tools: Fertility Quality of Life, Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), and selected subscales from Berlin Social Support Scales (BSSS).

Results: Among the respondents, 85% of women do not have children.The average age of the women studied was 34 years, while the average number of years of infertility treatment was 6 years. Respondents rate their quality of life the best in the area of relationship, but the worst in the area of emotions. More than 80% of respondents were at risk of developing depressive disorders of varying severity. Nevertheless, the vast majority are satisfied with the support they receive.

Conclusions: negative emotions that accompany women during in vitro process significantly affect their quality of life. They also contribute to an increased risk of mental disorders.

Citation

Wojciechowska P, Milska-Musa K A. Quality of life and mental state of women trying to conceive using the in vitro method. Eur J Transl Clin Med. 2024;7(1):106-112Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) indicates that on average 1 in 6 people of reproductive age worldwide experience infertility, which constitutes approximately 17.5% of the entire population [1-2]. The failure of natural conception may lead couples to use alternative reproductive methods, such as in vitro fertilization (IVF). In its report, the Polish Society of Reproductive Medicine and Embryology announced that in 2019, a total of approximately 22000 embryo transfers took place in Poland, resulting in over 8000 pregnancies [3]. Despite its popularity, trying to conceive via IVF may involve a number of emotional and mental challenges for women going through the process. Women may experience various emotional difficulties and sometimes even psychological problems such as anxiety, depression, eating disorders or low self-esteem. In the long term, social isolation, reduced communication and relationship difficulties between partners may occur [4]. The IVF process itself is not simple and includes challenges for women such as systematic visits and medical examinations, hormonal stimulation, ovarian puncture and embryo transfer [5].

The aim of our study was to determine the extent to which participation in the IVF procedure affects the quality of life and mental state of the respondents. We assessed whether this particular group of women is at risk of mental disorders and to what extent they need support from their partner, friends or family. There are many reports regarding the quality of life of women struggling with infertility in such countries as China, Hungary, Italy, Jordan and Kazakhstan [6-10]. The analysis of the literature indicates the niche nature of Polish reports in this area, which mentions the justification for continuing the research in the future.

Materials and methods

Using the Google Forms website, we developed a survey consisting of 66 questions divided into 4 sections. The first one contained general questions about socioeconomic data and the duration of infertility treatment, the number of embryo transfer attempts made, the number of children, miscarriages, stillbirths and the current costs incurred in connection with the IVF procedure. The second section contained the Fertility Quality of Life (FertiQol) questionnaire, an instrument used to assess the quality of life of people struggling with fertility problems [11]. The FertQol consists of two parts: basic and treatment. The basic part, consisting of 24 questions, was divided into 4 subscales: “Emotional,” “Mind and Body,” “Relational” and “Social.” The part regarding the treatment process contains 10 questions and focuses on two subscales: “Treatment Environment” (describing the medical environment) and the “Treatment” subscale (patient’s tolerance to treatment). Based on the results of the 6 subscales of the FertiQol, it is possible to assess the respondent’s quality of life (“Core”, the first part of the questionnaire) and treatment (“Treatment”, the second part), as well as obtain a general score in the assessment of health, quality of life and treatment (“Total score”). The higher the score, the higher the quality in the particular area of life. The third section of our survey consisted of questions from Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), to assess the risk of depression in the study group. The last section contained questions from selected subscales of the Berlin Social Support Scales (BSSS): “Perceived available support,” “Need for support” and “Looking for support.”

The study design assumed the participation of non-pregnant women during the IVF procedure. Due to significantly high number of women struggling with the problem of infertility, no upper age limit was set for the respondents. We shared our survey on social media groups associating women who were undergoing the IVF procedure. Participation in our study was voluntary and anonymous. We conducted our study from July to December 2023. Approval to conduct this project was obtained from the Independent Bioethics Committee for Scientific Research at the Medical University of Gdańsk (KB/386/2023). Statistical analysis of the obtained data was carried out using the Statistica software-version 13.1 PL (StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, USA) and Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, USA).

Results

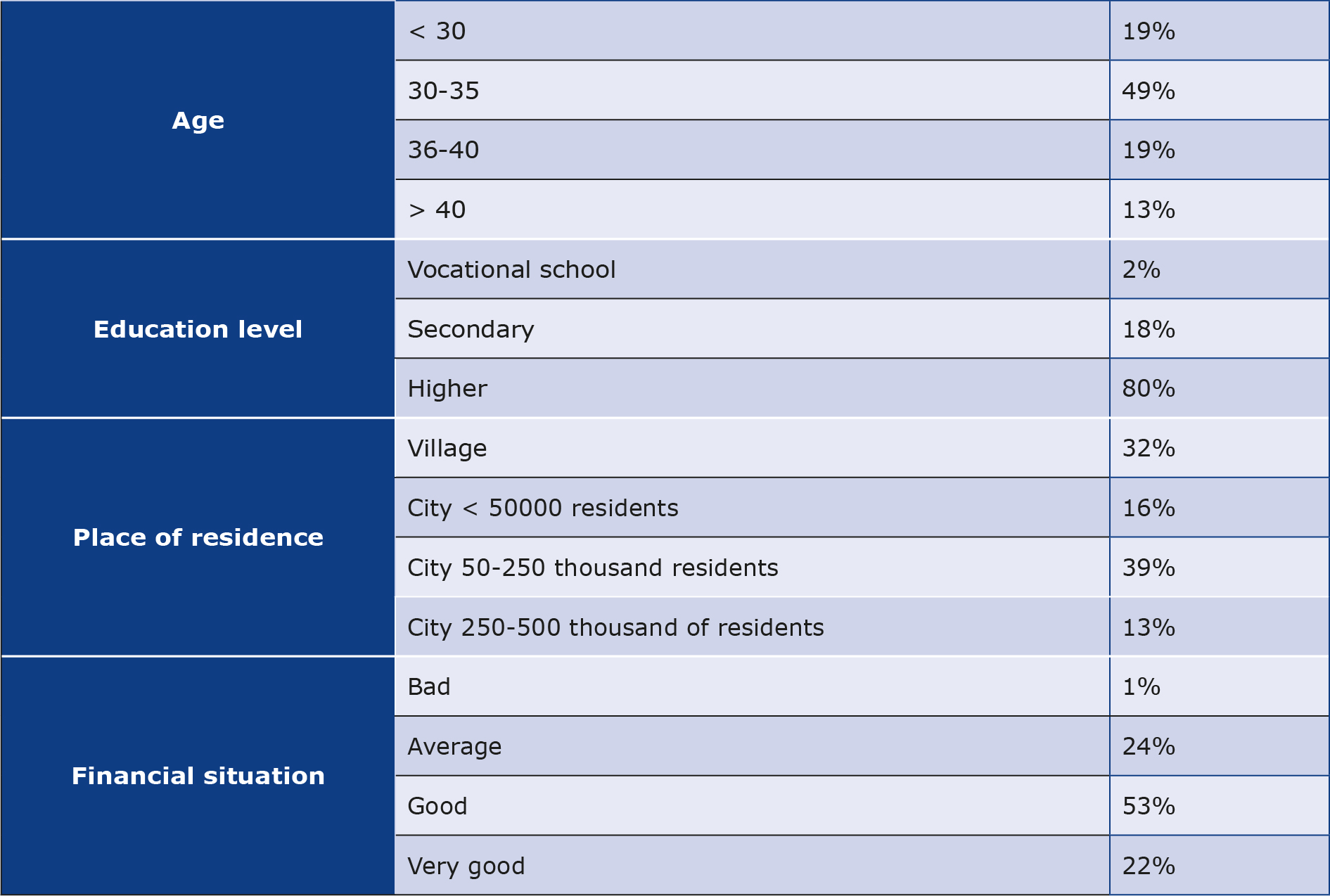

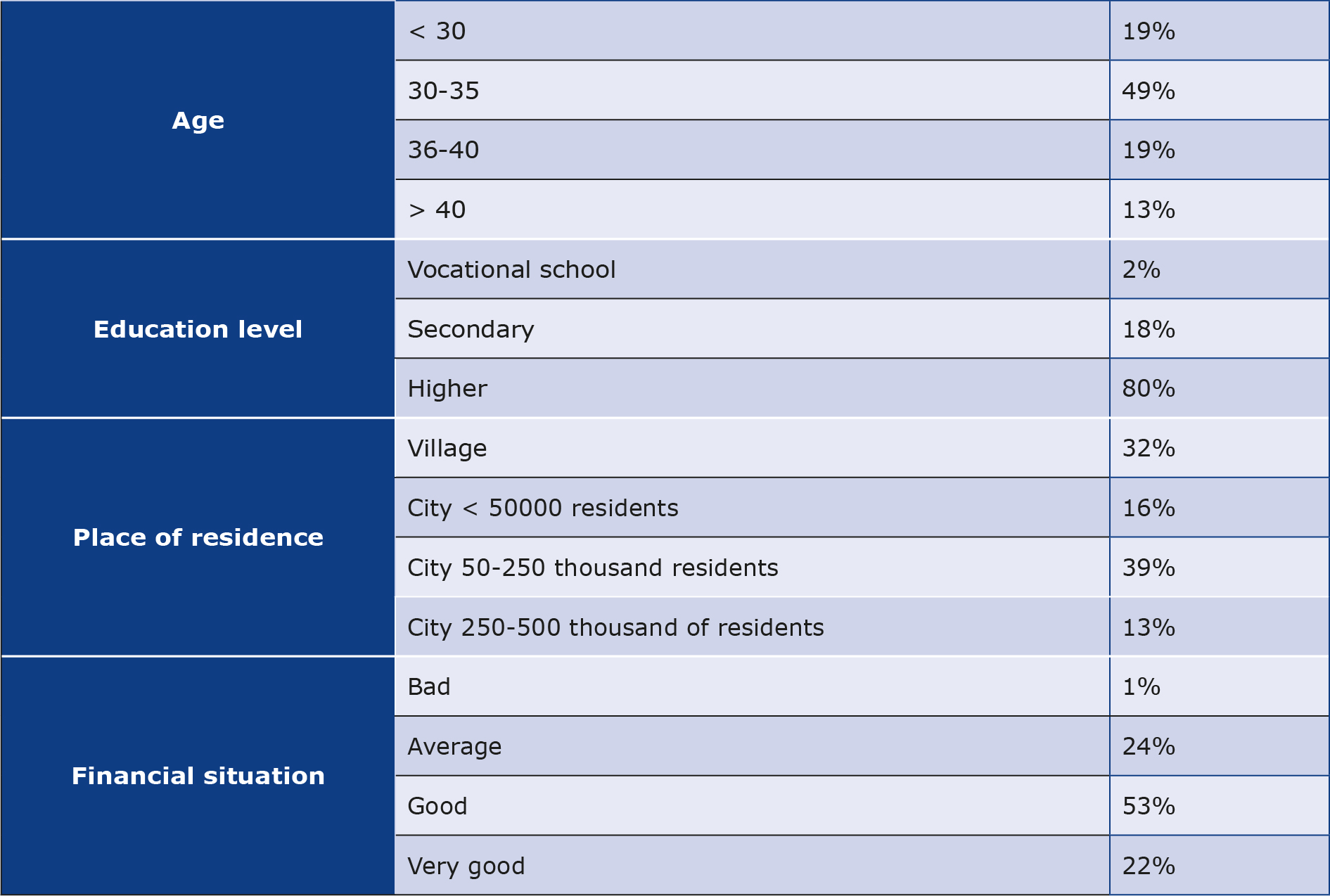

A total of 100 women participated in our study. The average age of the respondents was 34 years (x = 33.89), while the average declared duration of infertility treatment was approximately 6 years (x = 5.54). More details are presented in Table 1. The majority (85%) of the surveyed women did not have children, while the remaining 15% (n = 15) had experience with motherhood. Of the surveyed women, 13 (13%) had one child, and 2 (2%) had two children. More than half of the respondents (53%, n = 53), had never experienced a miscarriage. Whereas, 28 women (28%) once experienced the loss of a child before the 22nd week of pregnancy, 9 women (9%) admitted that such an event occurred twice, while 10 respondents (10%) experienced it three times or more. Among the respondents, 7% of them (n = 7) declared the experience of stillbirth, including six women (6%) once, and one woman (1%) experienced it twice. In the survey we asked about the number of attempts to transfer an embryo or embryos. Nearly 1/3 of women (n = 28, 28%) did not have such a procedure, which may indicate the initial stage of the IVF procedure. Almost half of the surveyed women (n = 45, 45%) have had 1 or 2 attempts, 21 women (21%) completed 3-4 attempts and 6 (6%) completed at least 5 attempts.

Table 1. Analysis of sociodemographic data of the respondents

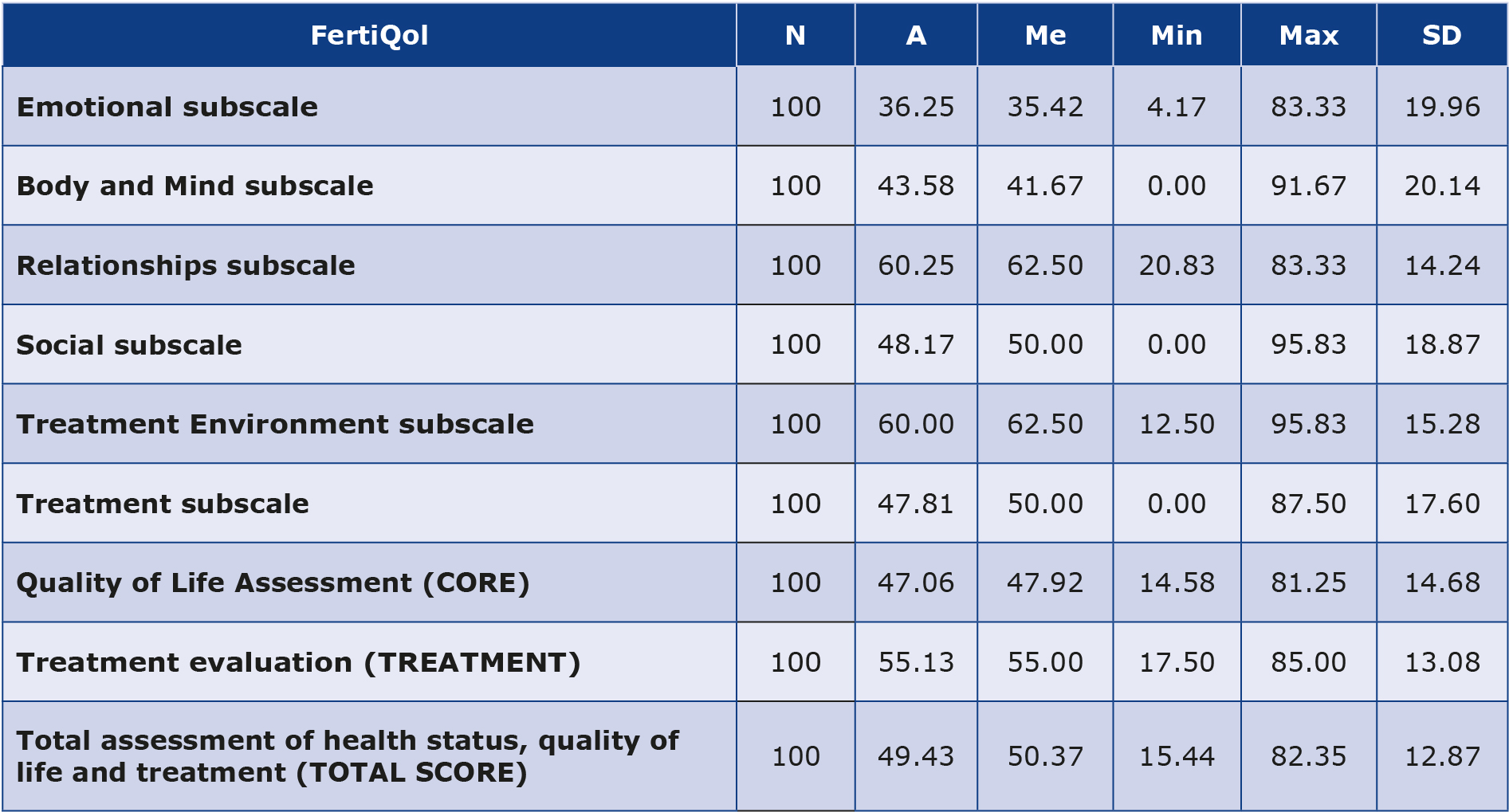

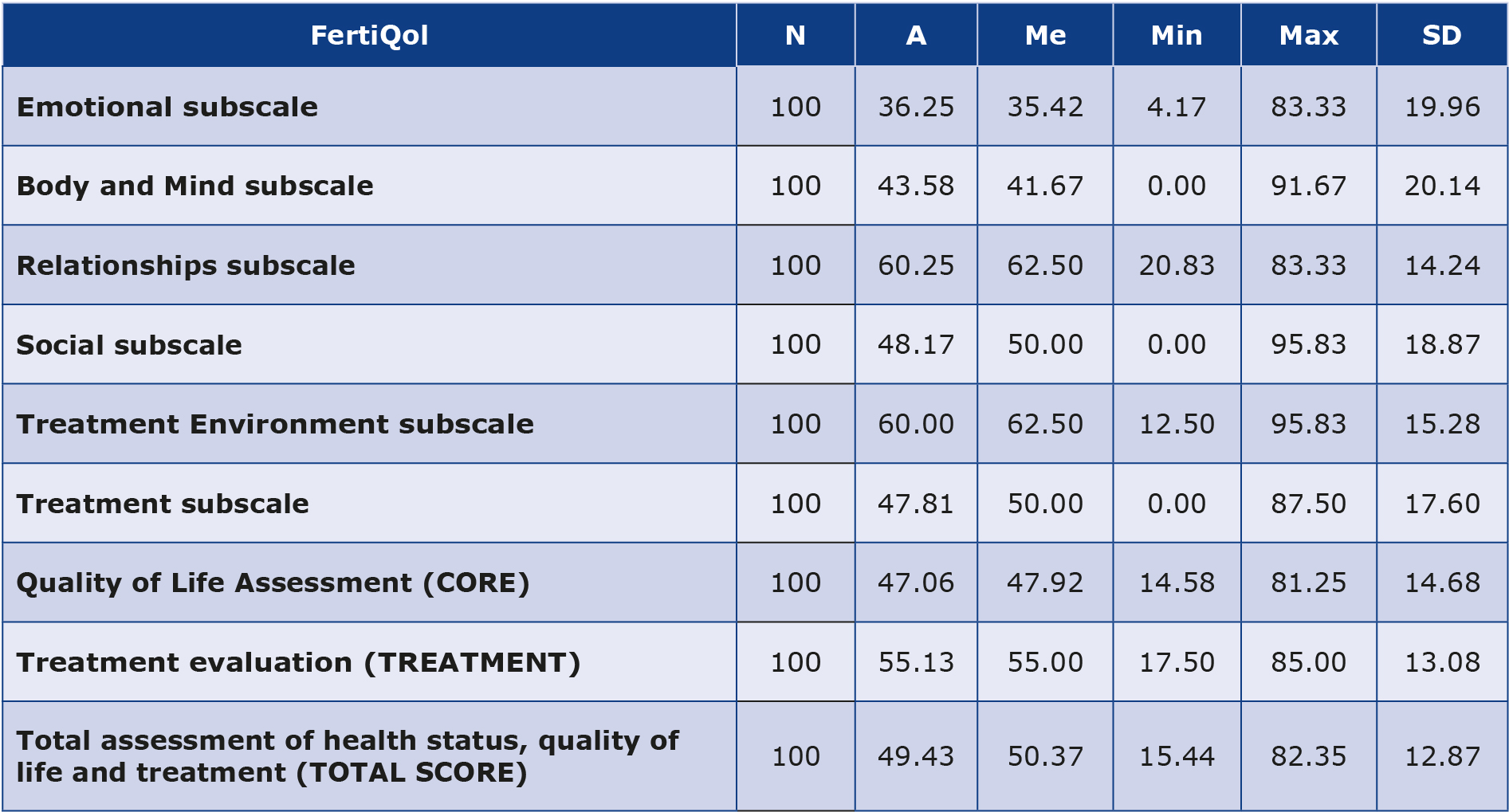

Basic statistics of the results obtained by the study group in the FertiQol are presented in Table 2. The respondents obtained the highest average score in the “Relationships” subscale, which may indicate that, in their opinion, fertility problems do not have a negative impact on the relationship or partnership in terms of sexuality, communication and commitment. The lowest average score concerned the “Emotional” subscale, which in turn suggests that negative emotions, (e.g. sadness and jealousy), significantly reduce the quality of life and mental state of women.

Table 2. Basic statistical analysis of the results obtained using the FertiQol questionnaire

N – number of respondents; A – average; Me – median; Min – minimum value; Max – maximum value; SD – standard deviation

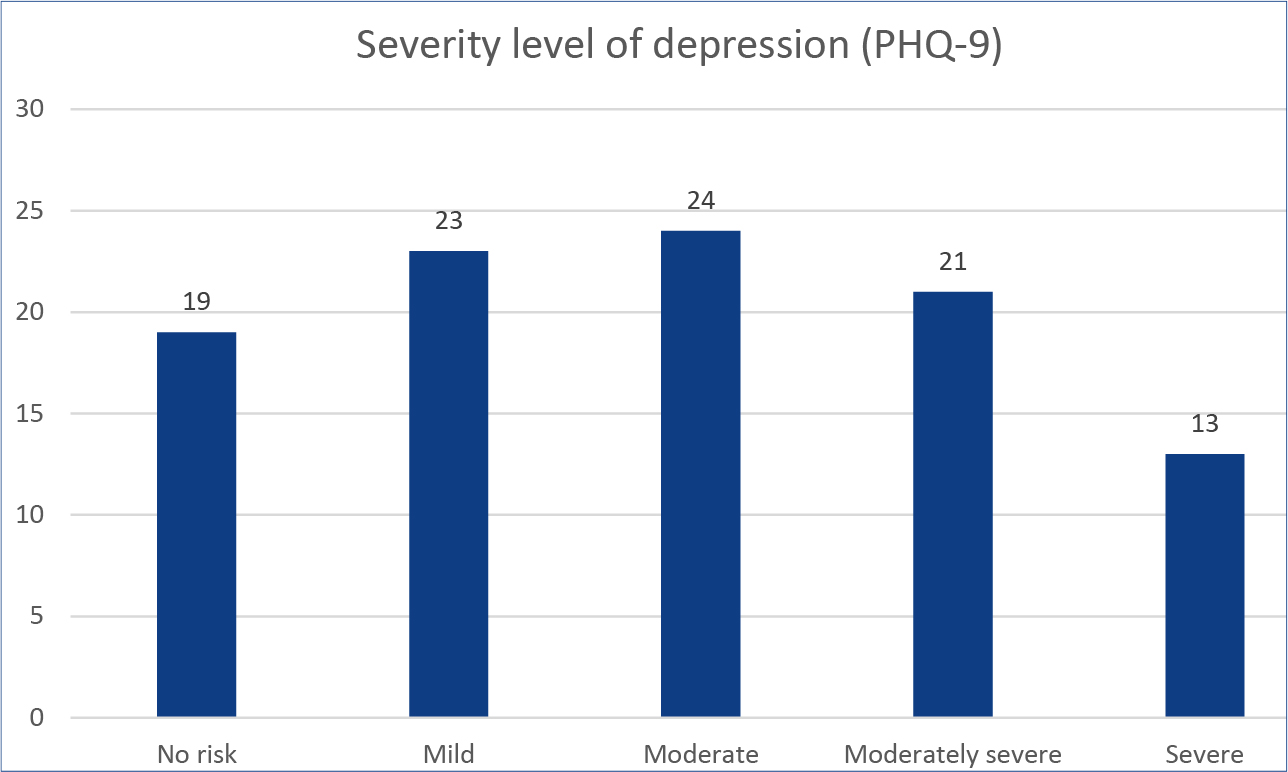

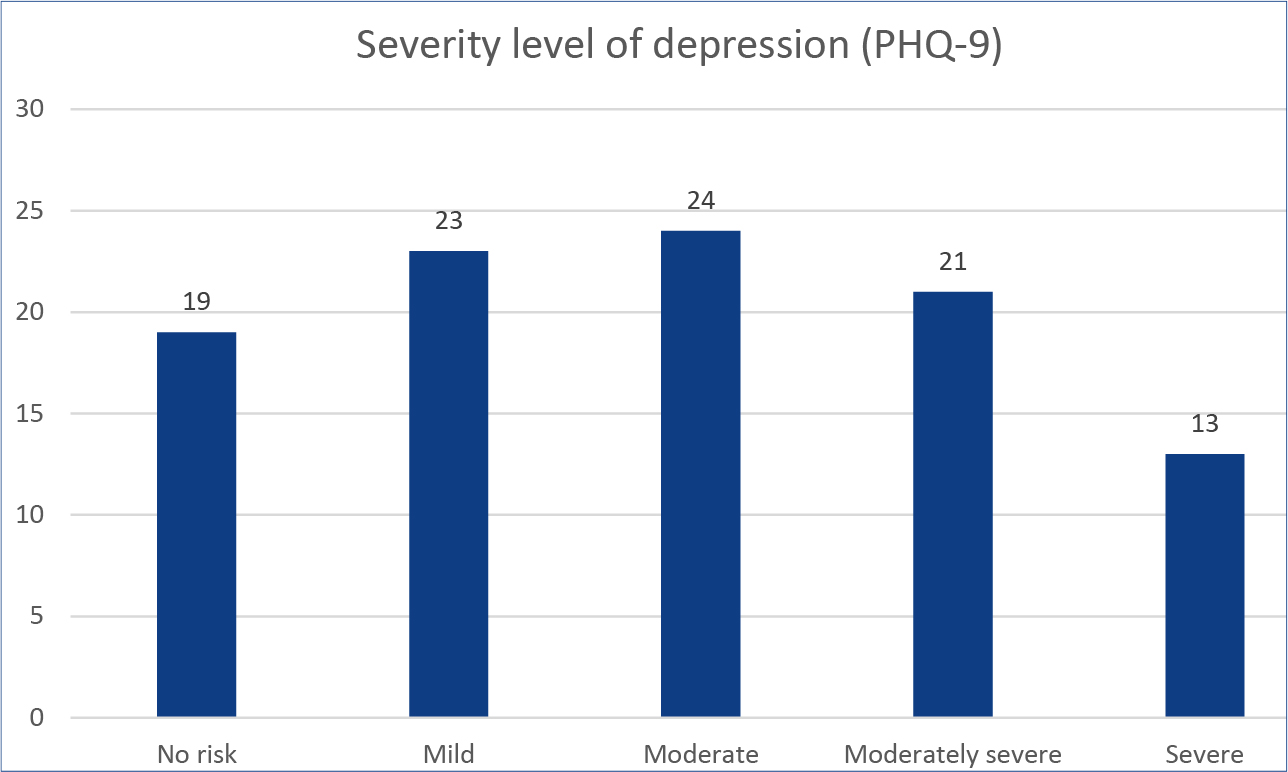

In our study group, the vast majority of women (n = 81, 81%) obtained results indicating the possibility of depression, with varying degrees of severity. Of the surveyed women, 23% (n = 23) obtained a result indicating the likelihood of mild depression, 24% (n = 24) – moderate depression, 21% (n = 21) – moderately severe depression and 13% (n = 13) – to a severe degree. A detailed analysis of the severity of depression dictated by the results obtained by the respondents is presented in Figure 1. Moderately severe and severe depression concerned over 1/3 of the respondents (n = 34, 34%), while only 19 women (19%) obtained a “no risk” result, indicating a probable lack of depression diagnosis. It should be emphasized that Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) is a screening tool, therefore it is advisable to consult with a specialist in order to confirm or rule out a diagnosis of depression.

Figure 1. Results obtained by respondents in the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)

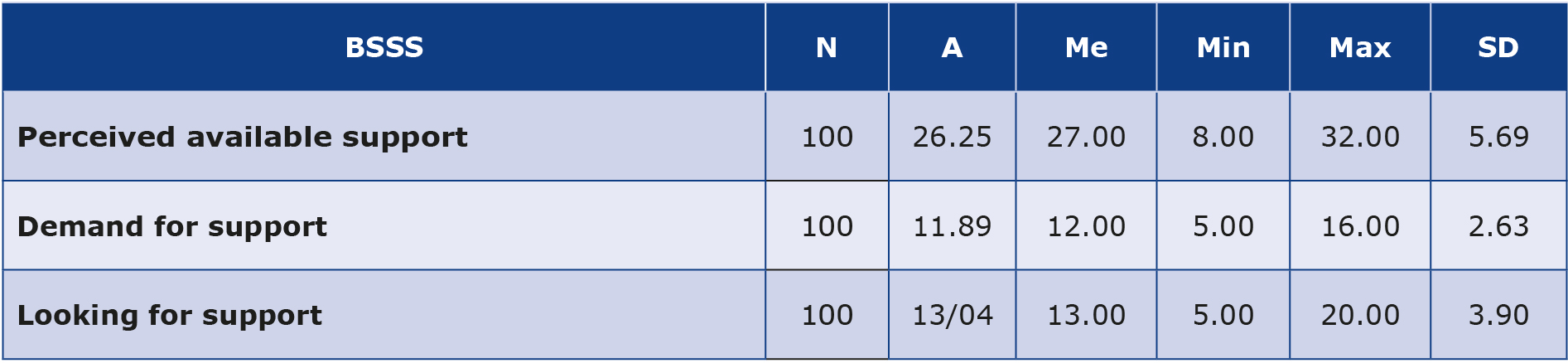

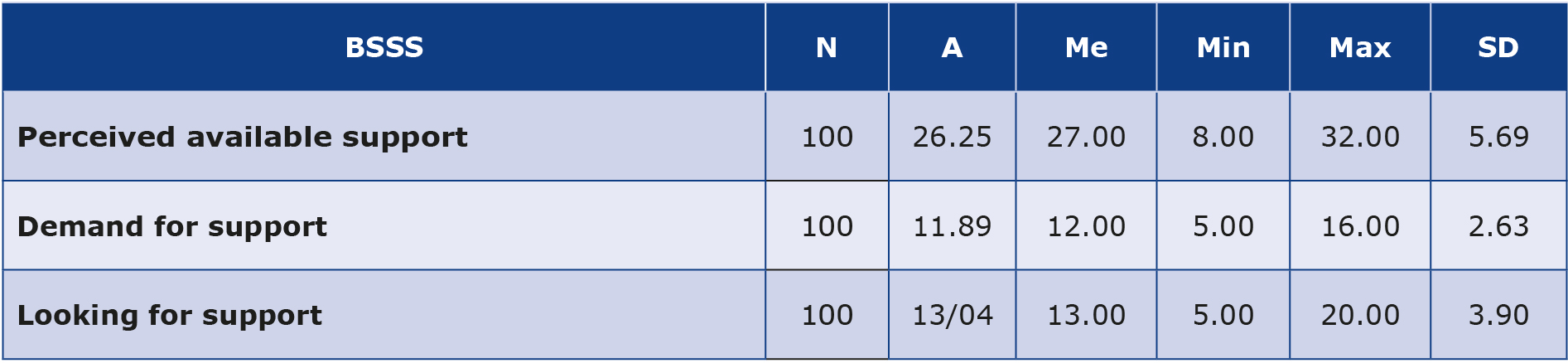

We used selected subscales from the Berlin Social Support Scales (BSSS) assessing social support from the perspective of the respondent. The descriptive statistics of the results obtained by the respondents in these subscales are presented in Table 3. The “Perceived available support” subscale consists of 8 questions and the maximum possible number of points to be scored was the highest of all selected subscales. The surveyed women obtained low average scores (x = 11.89) in the “Need for support” subscale and high average scores (x = 26.25) in the “Perceived available support” from close relatives’ subscale.

Table 3. Basic statistical analysis of the results obtained using the selected Berlin Social Support Scales (BSSS)

N – number of observations; A – average; Me – median; Min – minimum value; Max – maximum value; SD – standard deviation

Discussion

According to the report of by Statistics Poland, as of 2020 the average age of women at the time of delivering their first child in Poland was 28.5 years, compared to 22.7 years in the 1990s [12]. The average age of women in our study group was 34 years (x = 33.89). The results obtained may indicate that Polish women are trying to have their first child increasingly later in life. Nowadays, there is a trend related to the changes in the role of women in the society: increasingly more often women decide to give up the exclusive role of a caregiver at home in favor of independence, resourcefulness and personal development, which in turn may contribute to delaying the decision about motherhood [13]. Wylęgły determined the causes of the so-called “late motherhood” (parenthood after the age of 35): the importance of education and professional career in the lives of many young people and the lack of financial stability [14].

Mikołajczyk et al. reported about the increasing number of Polish women with higher education [15]. Our results are in line with that observation: over 80% (n = 80) of our respondents declared having higher education, which may be one of the factors indirectly contributing to late motherhood. The report by Statistics Poland emphasizes that in 2018- -2022 women were better educated compared to men. In the 30-34 years of age group, 47% of people (predominantly women) have higher education [16]. People of this age often feel more stable financially and in life, which may cause some women to consciously decide to become mothers at a later age, when they feel more ready to take on this challenge [17].

Every fifth respondent declared her place of residence in the countryside, while approximately 76% (n = 76) in areas considered urban. Most of the assisted reproduction centers are located in large agglomerations, which may be to the advantage of people living in cities, facilitating their access to treatment methods [18]. Environmental and lifestyle factors can also affect fertility [19].

When starting the IVF procedure, it is not possible to clearly determine how many months or years infertility treatment will last. The average duration of therapy declared by the respondents in the study was nearly 6 years (x = 5.54). Nearly half of the respondents, 47% (n = 47), declared having > 5 years of treatment for infertility. During this time, over 70% of respondents (n = 72) attempted to transfer an embryo or embryos. Most of them, 45% (n = 45) had only 1 or 2 attempts. The success rate of getting pregnant after the first embryo transfer is approximately 35%, but with age this probability declines [20]. Sharma et al. reported that the first ineffective IVF cycle may result in couples deciding to discontinue treatment due to the financial burden and existing mental and emotional problems [3].

Chanduszko-Salska compared ineffective infertility treatment to the loss of a loved one. The mourning process, strong emotions and stress, loss of faith in one’s own body and fertility, lack of faith in the possibility of having a child after numerous losses are factors that may have a significant impact on both the quality of life and the mental state of women [21]. Of the respondents, 28% (n = 28) had experienced a miscarriage, while 7% (n = 7) had a stillbirth. The loss of a longed-for offspring can cause strong reactions both somatic and psychological. Women can be afraid of getting pregnant again, thinking that they will lose it too [22]. Difficult psychological consequences indicate the need to consider psychological help dedicated to women at every stage of the IVF procedure. Psychological assistance should also be provided to women who have experienced a miscarriage or stillbirth.

The Public Opinion Research Center stated in its announcement that the assessment of the financial situation and income has the greatest impact on improving life satisfaction [23]. Slightly more than half of the respondents assessed their financial situation as “good.” Only 22% of respondents (n = 22) declared their financial situation as very good, and 24% (n = 24) as “average.” In the first quarter of 2023, the average household income per person in Poland was 7124.26 PLN [24]. The surveyed women were asked about the costs incurred in connection with the in vitro procedure. Nearly 60% of them (n = 59) chose the answer “over 20000 zł” (the option referring to the largest financial costs). One of the respondents commented that “one zero is missing” in the answer choices. The high costs of the IVF procedure result from numerous tests interfering with the woman’s body, ultrasound examinations, specialist consultations and the number of attempts to conceive the desired child [25]. Despite significant costs, not only financial ones, some women want to have biological offspring because it is a condition for them to feel stable and fulfilled in life [4].

“Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” [26]. The WHO emphasizes that mental health is an integral and necessary component of health. Warzecha showed that 87% of women did not seek the help of a psychologist before starting the IVF procedure. Only 6% of respondents admitted to consulting with a psychologist in the clinic where the procedure was to take place, and the reason for such a consultation was not specified [27].

The results obtained in the FertiQol confirmed that negative emotions have the greatest impact on the quality of life of women trying to conceive using the IVF method (the mean score of the “Emotional” subscale was x = 36.25). The obtained results confirm that difficulties with getting pregnant may contribute to a significant increase in stress, thus significantly increasing the risk of depression [28]. Wdowiak et al. compared 3 infertility treatment methods (assisted reproductive technology (ART), intrauterine insemination (IUI) and IVF), and observed that the women undergoing the IVF procedure obtained the highest result in the emotional domain [29]. Our results are opposite and this discrepancy may be due to the size of the study group, thus more research is needed. Wdowiak et al. also demonstrated that the choice of treatment method affects the assessment of the health status of women struggling with infertility, which may be an additional factor justifying providing psychological care to this group [29].

Limitations of the study

Our research has some limitations. Only 100 women took part in the study and the size of this study group limits the possibility to observe the trends that exist in the entire population. The short duration of the study (July to December 2023) could also affect the collected data. Moreover, our survey was made available only online on websites associating women trying to conceive using the IVF method. It would be justified to conduct further research in the future, modified to overcome the above-mentioned limitations.

Conclusions

The negative emotions that women experience during the IVF procedure significantly reduce their quality of life and may contribute to an increased risk of mental disorders. It is extremely important to receive support from one’s loved ones during this time. Women should be assured that they can receive specialist help from gynecologists, midwives, nurses and psychologists. Properly conducted psychoeducation could help women undergoing IVF understand the validity of the performed procedures, reduce the feeling of negative emotions and increase the level of knowledge and sense of control. Infertility is a global issue, therefore more in-depth studies are needed that include follow-up assessing the mental state of women undergoing the IVF procedure.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank each woman who participated in this study.

Funding

The work was not financed by any scientific and research institution, association or other entity, and the authors did not receive any grant.

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

| 1. |

Infertility [Internet]. World Health Organization. 2024 [cited 2024 Mar 13]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/infertility.

|

| 2. |

Infertility Prevalence Estimates, 1990–2021 [Internet]. Geneva; 2023. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/366700/9789240068315-eng.pdf.

|

| 3. |

Europejski Monitoring wyników leczenia Polska 2019 [in Polish] [Internet]. 2019. Available from: http://ptmrie.org.pl/sekcje-ptmrie/sekcja-lekarzy/raporty/europejski-monitoring-wynikow-leczenia-polska-2019.

|

| 4. |

Sharma A, Shrivastava D. Psychological Problems Related to Infertility. Cureus [Internet]. 2022; Available from: https://www.cureus.com/articles/115993-psychological-problems-related-to-infertility.

|

| 5. |

Dubiel-Zielińska P. Nadzieja i miłość matczyna w perspektywie in vitro [in Polish]. In: Chodźko E, Śliwa M, editors. Motyw miłości w literaturze polskiej i obcej [Internet]. Wydawnictwo Naukowe TYGIEL; 2019. p. 129. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Radoslaw-Trepanowski/publication/335993041_Zwiazek_milosci_i_religijnosci_w_swietle_badan_naukowych/links/5df51a204585159aa47e942f/Zwiazek-milosci-i-religijnosci-w-swietle-badan-naukowych.pdf#page=129.

|

| 6. |

Song D, Li X, Yang M, Wang N, Zhao Y, Diao S, et al. Fertility quality of life (FertiQoL) among Chinese women undergoing frozen embryo transfer. BMC Womens Health [Internet]. 2021;21(1):177. Available from: https://bmcwomenshealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12905-021-01325-1.

|

| 7. |

Volpini L, Mazza C, Mallia L, Guglielmino N, Rossi Berluti F, Fernandes M, et al. Psychometric properties of the FertiQoL questionnaire in Italian infertile women in different stages of treatment. J Reprod Infant Psychol [Internet]. 2020;38(3):324–39. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02646838.2019.1698017.

|

| 8. |

Szigeti F J, Grevenstein D, Wischmann T, Lakatos E, Balog P, Sexty R. Quality of life and related constructs in a group of infertile Hungarian women: a validation study of the FertiQoL. Hum Fertil [Internet]. 2022;25(3):456–69. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14647273.2020.1824079.

|

| 9. |

Al Obeisat S, Hayajneh A, Hweidi I, Abujilban S, Mrayan L, Alfar R, et al. Psychometric properties of the Arabic version of the Fertility Quality of Life (FertiQoL) questionnaire tested on infertile couples in Jordan. BMC Womens Health [Internet]. 2023;23(1):283. Available from: https://bmcwomenshealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12905-023-02437-6.

|

| 10. |

Suleimenova M, Lokshin V, Glushkova N, Karibayeva S, Terzic M. Quality-of-Life Assessment of Women Undergoing In Vitro Fertilization in Kazakhstan. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2022;19(20):13568. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/19/20/13568.

|

| 11. |

Boivin J, Takefman J, Braverman A. The fertility quality of life (FertiQoL) tool: development and general psychometric properties. Hum Reprod [Internet]. 2011;26(8):2084–91. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/humrep/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/humrep/der171.

|

| 12. |

Gustyn J, Lisiak E, Morytz-Balska E, Safader M. Polska w liczbach 2021 [in Polish] [Internet]. Warszawa; 2021. Available from: https://stat.gov.pl/files/gfx/portalinformacyjny/pl/defaultaktualnosci/5501/14/14/1/polska_w_liczbach_2021.pdf.

|

| 13. |

Wdowiak A, Tucki T. Aspekty środowiskowo-rodzinne i prawne zdrowia człowieka [in Polish] [Internet]. Włodawa: Międzynarodowe Towarzystwo Wspierania i Rozwoju Technologii Medycznej; 2015. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Beata-Zuraw/publication/308795167_Projekt_ogrodu_sensorycznego_przy_Osrodku_Rehabilitacyjno-Edukacyjno-Wychowawczym_w_Alojzowie_powiat_hrubieszowski/links/57f2884708ae886b897bfc60/Projekt-ogrodu-sensorycznego-przy-Osro.

|

| 14. |

Wylęgły K. Psychospołeczne uwarunkowania odraczania decyzji o macierzyństwie [in Polish]. Ogrody Nauk i Szt [Internet]. 2019 Aug 15;9:189–98. Available from: https://ogrodynauk.pl/index.php/onis/article/view/529.

|

| 15. |

Mikołajczyk M, Stankowska M. Aktywność zawodowa a macierzyństwo. Perspektywa matek małych dzieci [in Polish] [Internet]. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Akademii Pedagogiki Specjalnej im. Marii Grzegorzewskiej,; 2021. Available from: http://www.aps.edu.pl/media/tyzkkh0y/macierzynstwo_e-book2.pdf.

|

| 16. |

Deneka A, Grochowska-Subotowicz, E Jabłoński R. Human capital in Poland in the years 2018–2022 [Internet]. Warszawa, Gdańsk; 2023. Available from: https://stat.gov.pl/files/gfx/portalinformacyjny/pl/defaultaktualnosci/5501/8/9/1/kapital_ludzki_w_polsce_w_latach_2018-2022.pdf.

|

| 17. |

Mynarska M. Kiedy mieć dziecko? Jakościowe badanie procesu odraczania decyzji o rodzicielstwie [in Polish]. Psychol Społeczna [Internet]. 2011;6(18):226–40. Available from: https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=132367.

|

| 18. |

Członkowskie ośrodki medycyny rozrodu w Polsce [in Polish] [Internet]. Polskie Towarzystwo Medycyny Rozrodu i Embriologii. [cited 2024 Mar 13]. Available from: http://ptmrie.org.pl/o-ptmrie/czlonkowskie-osrodki-medycyny-rozrodu-w-polsce/.

|

| 19. |

Vander Borght M, Wyns C. Fertility and infertility: Definition and epidemiology. Clin Biochem [Internet]. 2018;62:2–10. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0009912018302200.

|

| 20. |

Misiurewicz-Gabi A. Na pomoc dzietności [in Polish]. Kurier Med [Internet]. 2020(5):34–6. Available from: https://www.termedia.pl/Journal/-147/pdf-41722-10?filename=Na pomoc.pdf.

|

| 21. |

J. C-S. Znaczenie pomocy psychologicznej i psychoterapii we wspomaganiu leczenia niepłodności partnerskiej [in Polish]. Postępy Andrologii Online [Internet]. 2016;3(1):15–27. Available from: https://postepyandrologii.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/29-07-2016-Chanduszko-Salska-01-1-2016.pdf.

|

| 22. |

Guzewicz M. Psychologiczne i społeczne konsekwencje utraty dziecka w wyniku poronienia [in Polish]. Civ Lex [Internet]. 2014;(1):15–27. Available from: https://cejsh.icm.edu.pl/cejsh/element/bwmeta1.element.desklight-6e42fd82-3a6d-4c31-a54f-fb1a2a93fc26/c/02_Guzewicz_M.pdf.

|

| 23. |

Pankowski K. Zadowolenie z życia w roku 2022 [in Polish]. Komun z badań Cent Badania Opinii Społecznej [Internet]. 2023;(5). Available from: https://www.cbos.pl/SPISKOM.POL/2023/K_005_23.PDF.

|

| 24. |

Komunikat w sprawie przeciętnego wynagrodzenia w pierwszym kwartale 2023 roku [in Polish] [Internet]. Główny Urząd Statystyczny. 2023 [cited 2024 Jun 6]. Available from: https://stat.gov.pl/sygnalne/komunikaty-i-obwieszczenia/lista-komunikatow-i-obwieszczen/komunikat-w-sprawie-przecietnego-wynagrodzenia-w-pierwszym-kwartale-2023-roku,271,40.html.

|

| 25. |

Malina A, Błaszkiewicz A, Owczarz U. Psychosocial aspects of infertility and its treatment. Ginekol Pol [Internet]. 2016 Jul 29;87(7):527–31. Available from: https://journals.viamedica.pl/ginekologia_polska/article/view/48289.

|

| 26. |

Health and well-being [Internet]. World Health Organisation. [cited 2024 Mar 13]. Available from: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/major-themes/health-and-well-being.

|

| 27. |

Warzecha M. Wpływ metody in vitro na zdrowie i funkcjonowanie kobiety oraz relacje małżeńskie [in Polish]. Teol i Moralność [Internet]. 1970;11(2(20)):191–226. Available from: https://pressto.amu.edu.pl/index.php/tim/article/view/7163.

|

| 28. |

Chanduszko-Salska J, Kossakowska K. Stres a objawy depresji i sposoby radzenia sobie u kobiet z niepłodnością i kobiet w ciąży wysokiego ryzyka. Acta Univ Lodz Folia Psychol [Internet]. 2018;(22):73–96. Available from: https://czasopisma.uni.lodz.pl/FoliaPsychologica/article/view/5422.

|

| 29. |

Wdowiak A, Anusiewicz A, Bakalczuk G, Raczkiewicz D, Janczyk P, Makara-Studzińska M. Assessment of Quality of Life in Infertility Treated Women in Poland. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2021;18(8):4275. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/18/8/4275.

|