The Ukrainian refugee crisis: its ethical aspects and the challenges for the Polish healthcare system – a descriptive review

Abstract

Since the start of the Russian Invasion of Ukraine on 24.02.2022, millions of people (mostly women and children) have fled Ukraine. Majority of them fled to Poland and providing adequate medical care for the massive influx of refugees is a considerable challenge for the Polish healthcare system, already burdened by the COVID-19 pandemic and staff shortages. The purpose of this study was to identify: the potential health problems of the incoming population, the legal and ethical aspects of the refugee crisis and its implications on public health. Combining the current data with previous research on refugee crises reveals a set of issues that need to be addressed. Ensuring continuity of chronic disease treatment, mental health, the risk of spreading vaccinable preventable diseases, high rates of tuberculosis, HIV and the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic are among the main concerns. In the near future, answers will have to be found to the emerging ethical questions of equal, safe access to care, implications of the language barrier, immunisation coverage, medical staff shortages, and existing legal and ethical regulations. As the emergency responses are addressed, the hosting countries need to prepare long-term resolutions.

Citation

Kolińska K, Paprocka-Lipińska A, Koliński M. The Ukrainian refugee crisis: its ethical aspects and the challenges for the Polish healthcare system – a descriptive review. Eur J Transl Clin Med. 2023;6(1):79-86Introduction

Despite the fact that the war in Ukraine has been going on since February 24th 2022, to date only a few articles have been published regarding the health problems of Ukrainian refugees [1-2]. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), World Health Organisation (WHO) and particular non-government organisations have regularly published reports providing important information elucidating the scale of this crisis and analysing the problems arising in connection with it [3-5]. Furthermore, the data allows us to look for solutions derived from knowledge gained during previous refugee crises [6]. For countries such as Poland, inexperienced at managing large-scale intake of refugees, this is a new situation to cope with, not disregarding its inevitable ethical and legal aspects.

The 1951 Geneva Convention states that all refugees should be guaranteed the same rights as the citizens of the host country. If this is not possible, this vulnerable group should be privileged in comparison with other categories of foreigners residing in the particular country [7]. Guaranteeing an adequate level of access to healthcare is a considerable challenge for host countries, already burdened by the COVID-19 pandemic and staff shortages [2]. While there is a need for emergency measures in case of immediate health threats, there also appears a need for continuity of treatment and long-term solutions. To find such most effective solutions it is crucial to accurately identify the scope of this crisis, the issues that accompany it and manage them effectively.

Material and methods

To find the data necessary for this review, we collected scientific publications and retrieved statistical data and information from governmental institutions as well as non-governmental international organisations. Our search was conducted through publications and sources available in English and Polish language. We focused on including in the analysis publications regarding challenges for refugees and the subsequent challenges to the healthcare system. Next, we confronted the above mentioned findings with the statistical data regarding the current Ukrainian refugee situation. We also reviewed the reference lists of selected publications for additional sources, applicable ethical and legal regulations and further internet resources.

Results

Finally, we included in our analysis 12 full text articles and 19 reports from international organisations.

Discussion

Scale of the problem

The influx of refugees from Ukraine to Poland has been consistent since the start of the Russian invasion. Although specifying the exact number of refugees from Ukraine in Poland continues to pose a challenge, one way of estimating the scale of this matter is by looking at the governmental data: over 1.5 million applications for foreigner status have been registered so far [8]. Of these 1.4 million, 69.5% of applicants are women and an additional 19.4% are males under 18 years old [8]. This corresponds to the data presented by WHO stating that approximately 96% are women and children [9]. Moreover, the data recorded by the UNHCR regarding the applications of refugees from Ukraine registered for temporary protection programmes (1.4 million) [10] is in accordance with the data presented by the Polish national registry.

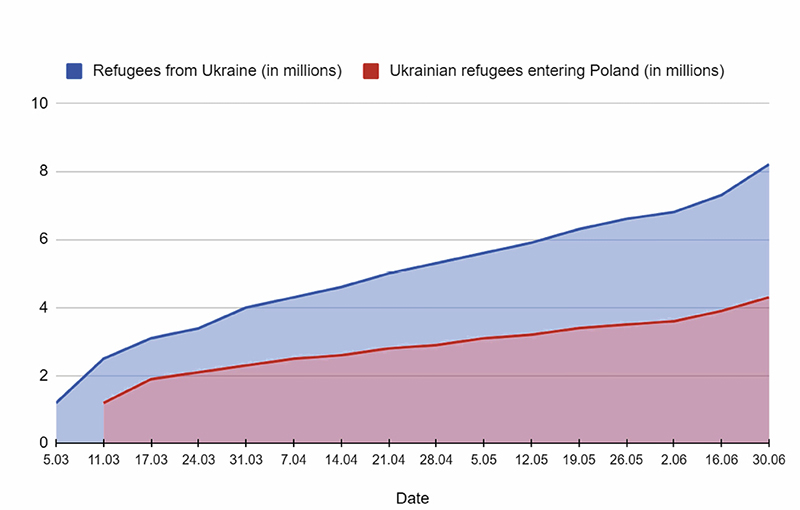

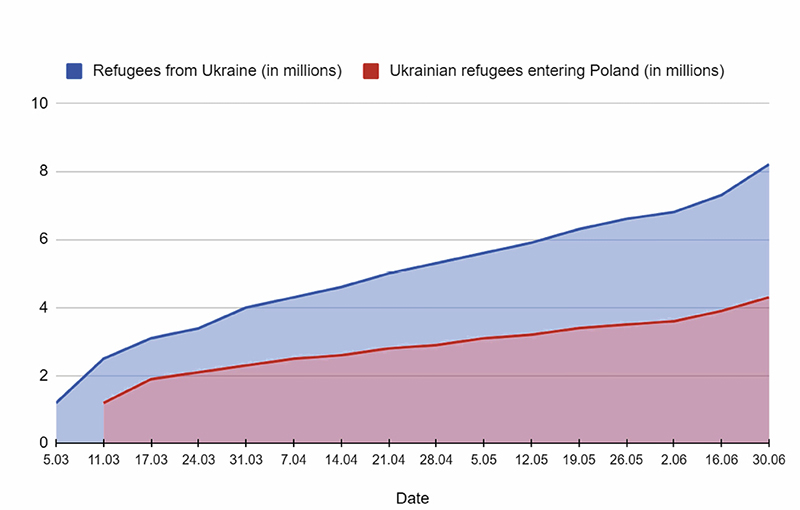

However, we must bear in mind that a significant number of Ukrainians will not be included in the above-mentioned records as they may perceive Poland as a place of temporary asylum before returning to Ukraine once they consider it safe or utterly necessary. For instance, according to data from the WHO, as of August 11th 2022 around 16.6 million refugees have been documented crossing the border between the two countries [11]. It is substantial to understand that this figure can be falsely magnified as it includes multiple crossings by the same person, yet it does not include refugees that have arrived in Poland indirectly through its neighbouring countries such as Slovakia or Czech Republic, nor does it take into account illegal crossings. Nevertheless, it is clear that not all of the refugees have remained in Poland. Once having crossed the Schengen area it is difficult to track them. Overall, Poland has been the main destination among the refugeereceiving countries in the first months of the crisis [3] as also illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 1. Total number of refugees from Ukraine and Ukrainian refugees entering Poland from 5.03 to 30.06.2022. Data from 16 WHO reports (5.03-30.06.2022): “Emergency in Ukraine: external situation report.” Available at: https://www.who.int/europe/emergencies/situations/ukraine-emergency/situation-reports-global

Identification of major health problems

It must be noted that refugees brought their health problems with them, therefore apart from emergency relief, it is expected that their illnesses will mainly burden the health system [6]. The WHO identifies the main health problems that are very likely to increase mortality and morbidity [12]. The “immediate health risks” noted among the refugees from Ukraine are COVID-19, measles, chronic infectious diseases (tuberculosis/HIV/HBV/HCV), cardiovascular disease, chronic respiratory diseases, diabetes as well as mental health problems such as depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [12].

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are a primary cause of mortality (91% of total deaths) in Ukraine, led by cardiovascular diseases (66%) and followed by cancer (13%), diabetes, chronic respiratory disease and mental health conditions [13]. In a survey conducted by the International Organisation for Migration, around 1 of every 5 respondents indicated that they or someone within their family needed to discontinue their medication by the start of the war; 85% of which stopped due to lack of availability of medication and 44% because they could not afford it [14]. Interruptions in treatment due to lack of availability or during transit can be fatal.

Mental health disorders are another significant problem to which refugees are particularly exposed. There is a low mental health awareness and a considerable level of stigmatisation in the Ukrainian population [12]. Before the war, only 3.2% of people suffering from depression received treatment [12]. 12.4% of Ukrainians had symptoms equivalent to a diagnosis of clinical depression, whereas suicide accounts for 2% of mortality in Ukraine [12-13]. Another concern is the rate of alcohol use disorders, four times higher than the global average (respectively 6%; 1.5% population prevalence), which can be intensified by trauma [13]. The risk of developing PTSD among refugees is very high [6]. Before the full-scale conflict, the risk of PTSD among people internally displaced in Ukraine was 30% [15]. In war-experienced populations, it is estimated that 1 in 5 people (22%) will have depression, anxiety, PTSD, bipolar disorder or schizophrenia [16]. An especially vulnerable group consists of the double displaced group (people displaced after having been already once displaced internally in Ukraine) [15]. Regrettably this data does not allow us to discern further between particular populations such as soldiers. In the upcoming months, an even greater increase of challenges regarding mental health is predicted: a surge of acute psychological distress cases, addiction problems, aggravation of chronic mental health issues along with lack of psychosocial support.

Furthermore, vaccine-preventable and chronic infectious diseases are rising concerns. Ukraine faced an epidemic of measles from 2017 to 2020. Even though measles vaccination coverage rose from 45% in 2016 to 87% in 2021, it is still below the recommended 95% population threshold [13, 17]. Ukraine has also not achieved this level of vaccination coverage for any of the core vaccinations: BCG, DTP3, Pol3, MCV and HepB3 [18]. Of particular concern is the polio outbreak of circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 (cVDVP2) with 20 cases identified in two regions of Ukraine in 2021 [19]. Thus, since vaccination coverage in Ukraine is among the lowest in the region, Poland and other host countries should take steps to prevent the spread of diseases preventable by vaccination of both their own and refugee populations. This is also of particular importance as 38.6% of Ukrainian refugees registered in Poland are below 18 years old [8].

In the WHO European Region refugees are at a higher risk of tuberculosis (TB) and there are inequalities in multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) ratio compared to the host populations [6]. Experience from other armed conflicts has shown that there is a risk of increasing TB cases and mortality [20]. This can be attributed to easier transmission in crowded settings, malnutrition interruptions, lack of or inadequate treatment, reactivation of latent infections and limited access to health care [20]. Ukraine presents a distinctively high TB rate worldwide, with an estimate of almost 30,000 new cases every year [21]. Globally, it is among the top 10 countries with the most elevated number of MDR-TB and it ranks as the second highest regarding the prevalence of HIV-TB coinfection (26%), when considering the WHO European Region [21].

HIV is another public health issue in Ukraine, with the second-highest prevalence within the WHO’s European Region [22]. There is also a disparity in treatment coverage, 57% in Ukraine compared to 82% in the EU, according to the WHO [21-22]. Refugees and migrants more often are diagnosed at a later stage of the HIV infection [6]. 44% of new HIV diagnoses in the WHO European Region in 2020 were reported in individuals who originated outside of the reporting country [22]. However, there are indications that a significant proportion of refugees and migrants, including those from countries with high HIV prevalence, become infected after their arrival in the WHO’s European Region [6].

The overlapping of the COVID-19 pandemic with the war makes the situation even more difficult. The Ukrainian population has a substantially lower uptake (35%) of a primary COVID-19 vaccination series in the total than the 72,7% EU/ EEA (European Economic Area) and Polish 59.6% average [23-24]. As the war started, around 5 million COVID-19 cases have been identified with a fivefold increase in detected SARS-CoV-2 infections between January and February 2022 [21, 25]. While there have been several waves of coronavirus infection incidence [21, 25], it must be considered these numbers immediately preceding the start of extensive migration towards neighbouring countries in Europe in addition to low percentages of vaccine uptake can result in a more severe course of the disease in unvaccinated individuals and a more dynamic transmission of the virus, further burdening the healthcare system. However, in the current situation, with eased restrictions in the neighbouring countries, it is difficult to predict what the real numbers are.

Ethical and legal aspects

The first regulations concerning the refugee issue appeared in the world after the Second World War. In 1951 the Geneva Convention (Refugee Convention) was adopted, which in 196 was supplemented by the New York Protocol, which in turn extended the Convention to non-European countries [7]. Poland adopted both documents 40 years later, in 1991 [26-27]. Since the adoption of the convention, many economically developed countries have been targets for populations leaving their countries of origin. Accordingly, there is a “non refoulement” principle, described in Article 33, which states that “No Contracting State shall expel or return (refouler) a refugee in any manner whatsoever to the frontiers of territories where his life or freedom would be threatened on account of his race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion” [26]. This consequently means taking measures to provide refugees with adequate protection and assistance by the state of their choice. The UNHCR reports have highlighted specific social and health problems of refugees, but also the impact of an increased population from other areas on the health security status of the population in the hosting country. It seems that given the particular threat of infectious diseases, it is reasonable to develop and use screening protocols for adults and children, additionally implementing vaccination programs to prevent epidemics. However, screening programs as well as the use of the resulting data may be controversial from an ethical point of view in the context of refugee and immigrant rights [28].

According to the Act on Patients՚ Rights and Patient Rights Ombudsman of 6th November 2008 – every person who reports to an institution providing medical services in Poland should receive medical assistance, in the light of the definition of “patient” in the Act, to which there are no additional criteria [29]. There is a lack of regulations concerning the process of provision of health services in the case of people who speak, for example, a language other than Polish. The main difficulties include collecting medical history and exercising the patient՚s right to information, as the information should be provided to the patient in an understandable way. There are no regulations stating explicitly whether the presence of an interpreter is indispensable.

In many cases, inviting an additional person who speaks the Ukrainian language into the interaction between the patient and the medical team has proved to be a practical and immediate solution. Furthermore, if the interpreter is a healthcare professional, then patient confidentiality is preserved. However, if this is not the case, the issue of protecting the patient’s confidentiality needs to be considered. Another solution could be the use of ready-made documents – for example, the medical history sheet translated into Ukrainian, available on the website of the Polish Chamber of Physicians and Dentists [30]. These materials were posted in early March 2022, intended primarily for doctors and dentists working in hospital emergency departments and in medical institutions in border regions. In addition, the Ministry of Health has launched an application, which helps patients to communicate with medical staff in Polish, Ukrainian, Russian or English [31]. Some further tools are publicly available multilingual applications such as Symptomate (after describing their symptoms users are given instructions on where they should go to get appropriate help) [32] or search engines maintained by medical organisations, e.g. the Polish Society of Family Medicine [33].

The need to provide services to a patient who does not understand Polish carries a risk of committing a medical error arising from the lack of clear communication. In addition to discussing the treatment plan formally, the patient’s informed consent to provide health services is needed. A number of questions arise in relation to this issue: should the informed consent for medical service for a refugee be translated by a sworn translator? Can an informed consent form be accepted in a foreign language? Can the consent be signed on a form prepared in a language not understood by the patient? In the legal act regulating the practice of the medical and dental professions, there are no additional references concerning the above-mentioned issues [34].

The Polish Code of Medical Ethics, the document regulating the ethical side of practising the medical profession, contains general references to acting in the best interests of the patient, regardless of age, sex, race, genetic endowment, nationality, religion, social affiliation, material situation, political views or other conditions [35]. There are no descriptions of additional duties of the doctor and dentist regarding people arriving from foreign countries due to danger. In the United States of America, regular discussions have taken place within the structures of The American Medical Association which published resources for practising physicians regarding interpreting the provisions of the Code of Medical Ethics in relation to the medical care for patients who are immigrants, refugees or asylum seekers [36]. Such discussion certainly is necessary in the structures of the Polish health care system, taking into account the protracted state of war in Ukraine.

The question of guaranteeing equal access to health services in a situation of organisational difficulties and deficits in public health care remains to be thoroughly worked out. The legislature adopted on March 12th 2022, a law on assistance to citizens of Ukraine in connection with the armed conflict on the territory of their country and importantly, this legislation entered into force retroactively from February 24th 2022 [37]. There were additional provisions in the existing legislation – an amendment to the Act on Doctor and Dentist in art. 77, art. 85 (by adding provision that doctor or dentist provides health services to persons whose stay in Poland is legal) concerning reimbursement of medicines and art. 86 regulating the work of nurses and midwives. In practice, however, there arise specific problems as, for instance, a situation when a Ukrainian citizen requires medical assistance yet the medical personnel cannot recognize their entitlement to a reimbursed health service.

At present, the introduced solutions seem to have worked properly through mechanisms such as disinterested willingness to help, common sense in providing health services despite difficulties in communicating with patients and the goodwill of both parties. In order to prevent possible abuses, the situation will certainly require long-term solutions which above all must address the key ethical question: how to reconcile the well-being and safety of the host community with the wellbeing and health security of an increased wave of refugees?

An attempt to identify long-term problems

The war in Ukraine has been going on for more than one year, whereas the experience with previous armed conflicts suggests no prompt resolution. The role of international organisations is crucial to contribute coordinated help. Non-governmental organisations such as Médecins Sans Frontières and the International Red Cross are supporting the management and logistics of reception centres and providing medical and shelter-related supplies in Poland as well as other countries neighbouring Ukraine [38-39]. The WHO together with other international agencies developed initiatives aimed at coordinating their efforts, such as the Refugee Health Extension, strengthening access to healthcare [40-41]. Similarly, the European Center for Disease Control (ECDC) has developed guidelines for disease surveillance [42] while WHO delivered large quantities of medical supplies, e.g. antiretroviral drugs to Poland or PCR reagents to Romania [40].

Overall, an equally relevant task pertains to the refugeehosting countries as they need to prepare for long-term support and the challenges that come with it.

A question arises whether we are able to guarantee a responsive and safe access to medical care without discrimination for both Ukrainians and refugees originating elsewhere? The available literature indicates that refugees and migrants, despite often initially being in better health than host populations, became more susceptible to illness over time [6]. Such a circumstance is attributed to inequalities and barriers to accessing healthcare, social determinants of health including poor living and sanitation conditions, low vaccination coverage, exposure to communicable diseases and disruptions in continuity of care [6]. It is therefore important to guarantee refugees prompt and accessible healthcare in the host countries.

Large migrant populations moving in crowded conditions can easily spread communicable diseases. During other crises, such outbreaks have been observed in migrant populations, including outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases in migrants from Eastern Europe [43]. In addition, given the low levels of immunisation and the high vaccination hesitancy in Ukraine along with the COVID-19 pandemic, widely available immunisation programmes must be guaranteed to ensure the safety of refugee populations and host countries. Then, another question arises whether it is ethical for us to require mandatory vaccinations for refugees?

Guaranteeing an adequate level of extemporary care along with continuing long-term therapy is only possible with an adequate proportion of medical staff. With almost half of the refugees in Poland being children [8], there has been a significant increase in the paediatric population that needs care, thus it seems that paediatricians and general practitioners will be particularly burdened. Poland has among the fewest of physicians per population in the European Union (EU), just 2.4 practising doctors per 1000 population and it is the second-lowest in Europe behind Turkey [44]. Lewtak et al. estimated that 2300 physicians and 5000 nurses per every million of incoming refugees are needed to maintain current the statistics [2]. Nonetheless, how to manage sufficient care with the existing shortage of medical professionals? Facilitating a pathway for the recognition of qualifications appears as a solution, but questions emerge as to how qualifications, in particular language competences, should be recognised. Such a solution, to be ethically justified, should be the same for all refugees regardless of their country of origin.

Furthermore, according to the existing literature the main issue identified by both refugees and healthcare providers is the above-mentioned language barrier [45]. This poses a considerable obstacle at every stage of medical services provision. Hence, the need for interpreters and translators is acknowledged.

Among other challenges mentioned by health care providers are time limitations, lack of competence and skills, emotional burden and cultural differences [46]. The geographical and cultural proximity to Ukraine seems to reduce the latter yet, it remains significant [47]. Poland and other host countries shall find the optimal solutions on how to respond to the health needs of refugees and the following relevant questions.

Conclusions

Providing medical care for refugees from Ukraine poses a completely new challenge for the Polish health care system. The outbreak of the war in Ukraine on February 24th 2022 and a rapidly growing wave of refugees crossing the Polish-Ukrainian border revealed deficiencies related to providing health services for the incoming population, which were and still are mainly women and children. While there was a need for emergency measures in case of immediate health threats, there also appeared a need for continuity of treatment and long-term solutions.

Funding

None.

Conflicts of interests

None.

Editor-in-Chief's Commentary

Ukraine is very important to us. Just as Poland had in the past, Ukraine is currently defending itself against an attack and fighting for its freedom, independent identity and full independence. The large number of Ukrainian citizens (mainly women and children) who found refuge in Poland, presented an unprecedented challenge for the local health care system. Providing both inpatient and outpatient care to refugees from Ukraine in the face of the crisis, we gained experience and learned lessons that ought to be shared with others.

For this reason, we decided to publish the article "The Ukrainian refugee crisis: its ethical aspects and challenges for the Polish healthcare system – a descriptive review."

Although it is outside the scope of our Journal, this article contains an analysis of a timely and important problem of the modern world. According to the authors, this particular crisis revealed major deficiencies related to the provision of health services to the refugee population. Therefore, it requires immediate and often extraordinary actions to protect the health of Ukrainian refugees not only in the event of urgent illness, but also long-term medical care.

Editor-in-chief of EJTCM

Prof. Dariusz Kozłowski MD, PhD

References

| 1. |

Jankowski M, Gujski M. Editorial: The public health implications for the refugee population, particularly in Poland, due to the war in Ukraine. Med Sci Monit. 2022;28:e936808. Available from: https://medscimonit.com/abstract/full/idArt/936808.

|

| 2. |

Lewtak K, Kanecki K, Tyszko P, Goryński P, Bogdan M, Nitsch-Osuch A. Ukraine war refugees – threats and new challenges for healthcare in Poland. J Hosp Infect. 2022;125:37-43. Available from: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2022.04.006.

|

| 3. |

Ukraine emergency situation reports (global) [Internet]. World Health Organization. [cited 2022 Nov 8]. Available from: https://www.who.int/europe/emergencies/situations/ukraine-emergency/situation-reports-global.

|

| 4. |

Ukraine refugee situation [Internet]. Operational Data Portal. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 2022 [cited 2022 Mar 28]. Available from: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/ukraine.

|

| 5. |

Ukraine [Internet]. ReliefWeb Response. [cited 2022 Nov 8]. Available from: https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/operations/ukraine.

|

| 6. |

Report on the health of refugees and migrants in the WHO European Region: no public health without refugee and migrant health (2018) [Internet]. World Health Organization. 2018 [cited 2022 Jul 3]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/report-on-the-health-of-refugees-and-migrants-in-the-who-european-region-no-public-health-without-refugee-and-migrant-health.

|

| 7. |

UNHCR: Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees. [Internet] The United Nations High Commission for Refugees. 2022 [cited 2022 Jul 3]. Available from: https://www.unhcr.org.

|

| 8. |

Zarejestrowane wnioski o nadanie statusu UKR w związku z konfliktem na Ukrainie, stan na 3.11.2022 [in Polish]. [cited 2022 Nov 6] Available from: https://dane.gov.pl/pl/dataset/2715/resource/42530/table?page=1&per_page=20&q=&sort=.

|

| 9. |

Poland: UNHCR Factsheet (17 June 2022) [Internet]. UNHCR Operational Data Portal (ODP). [cited 2022 Jul 2]. Available from: https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/93757.

|

| 10. |

Poland: UNHCR Poland operational update – 15 October 2022 [Internet]. UNHCR Operational Data Portal (ODP). [cited 2022 Nov 8]. Available from: https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/96490.

|

| 11. |

Emergency in Ukraine: external situation report #16, published 30 June 2022: reporting period: 16-29 June 2022 [Internet]. World Health Organisation. 2022 [cited 2022 Jul 2]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-EURO-2022-5152-44915-65208.

|

| 12. |

Ukraine crisis. Public health situation analysis: refugee-hosting countries, 17 March 2022 [Internet]. World Health Organisation. 2022 [cited 2022 Jul 2]. Available from: https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/WHO-EURO-2022-5169-44932-63918.

|

| 13. |

Ukraine: Public health situation analysis (PHSA) - long-form (last update: April 2022) [Internet]. ReliefWeb. 2022 [cited 2022 Jul 2]. Available from: https://reliefweb.int/report/ukraine/ukraine-public-health-situation-analysis-phsa-long-form-last-update-april-2022.

|

| 14. |

Ukraine – internal displacement report – general population survey round 3 (11 – 17 April 2022) [Internet]. Iom.int. [cited 2022 Jul 2]. Available from: https://displacement.iom.int/reports/ukraine-internal-displacement-report-general-population-survey-round-3-11-17-april-2022.

|

| 15. |

Roberts B, Makhashvili N, Javakhishvili J, Karachevskyy A, Kharchenko N, Shpiker M, et al. Mental health care utilisation among internally displaced persons in Ukraine: results from a nation-wide survey. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2019;28(1):100-11. Available from: http://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796017000385.

|

| 16. |

Charlson F, van Ommeren M, Flaxman A, Cornett J, Whiteford H, Saxena S. New WHO prevalence estimates of mental disorders in conflict settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2019;394(10194):240-8. Available from: http://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30934-1.

|

| 17. |

Hübschen JM, Gouandjika-Vasilache I, Dina J. Measles. Lancet. 2022;399(10325):678-90. Available from: http://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(21)02004-3.

|

| 18. |

Ukraine: WHO and UNICEF estimates of immunisation coverage: 2021 revision [Internet]. [cited 2022 Jul 2]. Available from: https://data.unicef.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/ukr.pdf.

|

| 19. |

UNICEF welcomes Ukraine’s plan to stop polio outbreak [EN/UK] [Internet]. ReliefWeb. 2022 [cited 2022 Jul 2]. Available from: https://reliefweb.int/report/ukraine/unicef-welcomes-ukraine-s-plan-stop-polio-outbreak-enuk.

|

| 20. |

Dahl VN, Tiberi S, Goletti D, Wejse C. Armed conflict and human displacement may lead to an increase in the burden of tuberculosis in Europe. Int J Infect Dis. 2022;124:S104-6 Available from: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2022.03.040.

|

| 21. |

Operational public health considerations for the prevention and control of infectious diseases in the context of Russia’s aggression towards Ukraine [Internet]. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 2022 [cited 2022 Jul 3]. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/operational-public-health-considerations-prevention-and-control-infectious.

|

| 22. |

HIV/AIDS surveillance in Europe 2021 (2020 data) [Internet]. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 2021 [cited 2022 Jul 3]. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/hiv-aids-surveillance-europe-2021-2020-data.

|

| 23. |

Mathieu E, Ritchie H, Rodés-Guirao L, Appel C, Giattino C, Ortiz-Ospina E, et al. Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19). Our World in Data [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2022 Jul 3]; Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations?country=POL~UKR.

|

| 24. |

COVID-19 Vaccine Tracker [Internet]. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. [cited 2022 Jul 3]. Available from: https://vaccinetracker.ecdc.europa.eu/public/extensions/COVID-19/vaccine-tracker.html.

|

| 25. |

COVID live - Coronavirus statistics – worldometer [Internet]. Worldometer. [cited 2022 Jul 3]. Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/.

|

| 26. |

Konwencja dotycząca statusu uchodźców, sporządzona w Genewie dnia 28 lipca 1951 r. [in Polish]. ISAP. Dz.U. 1991 nr 119 poz. 515. Available from: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU19911190515.

|

| 27. |

Protokół dotyczący statusu uchodźców, sporządzony w Nowym Jorku dnia 31 stycznia 1967 r. [in Polish]. ISAP. Dz.U. 1991 nr 119 poz. 517. Available from: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU19911190517.

|

| 28. |

Pérez-Molina JA, Álvarez-Martínez MJ, Molina I. Medical care for refugees: A question of ethics and public health. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2016;34(2):79-82. Available from: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.eimc.2015.12.007.

|

| 29. |

Ustawa z dnia 6 listopada 2008 r. o prawach pacjenta i Rzeczniku Praw Pacjenta [in Polish]. ISAP. Dz.U. 2009 nr 52 poz. 417. Available from: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20090520417.

|

| 30. |

The medical history sheet translated into Ukrainian [in Polish/Ukrainian]. [Internet].[cited 2022 Jul 3]. Available from: https://nil.org.pl/dzialalnosc/pomoc-dla-ukrainy/5956-slowniki-polsko-ukrainskie-i-%20karta-wywiadu-lekarskiego.

|

| 31. |

LikarPL [Internet]. Gov.pl. [cited 2022 Nov 8]. Available from: https://likar.mz.gov.pl.

|

| 32. |

Symptomate [in Polish] [Internet]. Symptomate.com. [cited 2022 Nov 8]. Available from: https://symptomate.com/pl.

|

| 33. |

Medical Help Search Engine / Wyszukiwarka jednostek medycznych [Internet]. Medicalhelp.pl. [cited 2022 Nov 8]. Available from: https://medicalhelp.pl.

|

| 34. |

Ustawa z dnia 5 grudnia 1996 r. o zawodach lekarza i lekarza dentysty [in Polish]. ISAP [Internet]. Dz.U. 1997 Nr 28 poz. 152. [cited 2022 Jul 3]. Available from: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU19970280152.

|

| 35. |

Polish Medical Ethics Code, uniform text of 2 January 2004, with the amendments passed on 20 September 2003. In: 7th Extraordinary National Medical Congress. Warsaw; 2004.

|

| 36. |

Harbut RF. AMA policies and Code of Medical Ethics’ opinions related to health care for patients who are immigrants, refugees, or asylees. AMA J Ethics. 2019;21(1):E73-77. Available from: http://doi.org/10.1001/amajethics.2019.73.

|

| 37. |

Ustawa z dnia 12 marca 2022 r. o pomocy obywatelom Ukrainy w związku z konfliktem zbrojnym na terytorium tego państwa [in Polish] [Internet]. ISAP [cited 2022 Jul 3]. Available from: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20220000583.

|

| 38. |

Ukraine: Massive, urgent response needed to meet soaring needs [Internet]. International Committee of the Red Cross. 2022 [cited 2022 Nov 8]. Available from: https://www.icrc.org/en/document/ukraine-massive-urgent-response-needed-meet-soaring-needs.

|

| 39. |

Responding as millions of people flee war in Ukraine [Internet]. Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) International. [cited 2022 Nov 8]. Available from: https://www.msf.org/msf-response-war-ukraine.

|

| 40. |

WHO Ukraine crisis response: August 2022 bulletin [Internet]. World Health Organization. 2022 [cited 2022 Nov 8]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-EURO-2022-6172-45937-66318.

|

| 41. |

Key considerations for on-site assessment of refugee transit points and accommodation centres in the EU/EEA in the context of the refugees fleeing the war in Ukraine [Internet]. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 2022 [cited 2022 Nov 8]. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/key-considerations-refugee-transit-points-and-accommodation-ukraine.

|

| 42. |

Handbook on implementing syndromic surveillance in migrant reception/detention centres and other refugee settings. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; Stockholm 2016 [cited 2022 Nov 8]. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/media/en/publications/Publications/syndromic-surveillance-migrant-centres-handbook.pdf.

|

| 43. |

Deal A, Halliday R, Crawshaw AF, Hayward SE, Burnard A, Rustage K, et al. Migration and outbreaks of vaccine-preventable disease in Europe: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21(12):e387-98. Available from: http://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00193-6.

|

| 44. |

Health at a Glance: Europe 2020: State of Health in the EU Cycle. OECD Publishing 2020; Paris. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1787/82129230-en.

|

| 45. |

Gil-Salmerón A, Katsas K, Riza E, Karnaki P, Linos A. Access to healthcare for migrant patients in Europe: Healthcare discrimination and translation services. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(15):7901. Available from: http://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18157901.

|

| 46. |

Kavukcu N, Altıntaş KH. The challenges of the health care providers in refugee settings: A systematic review. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2019;34(2):188-96. Available from: http://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X19000190.

|

| 47. |

Długosz P, Kryvachuk L, Izdebska-Długosz D. Problemy ukraińskich uchodźców przebywających w Polsce [in Polish] [Internet]. Unpublished; 2022. Available from: https://psyarxiv.com/rj2hk/download?format=pdf.

|