Abstract

Sarcomas are malignant tumors of mesenchymal origin. They comprise of < 1% adult malignancies and about 15-20% of pediatric malignancies. These tumors are subdivided into bone and cartilage sarcomas and soft tissue type. Sarcomas of the maxillofacial region comprise 5-10% of all sarcomas and < 1% of all malignancies of this part of the body. Usually sarcomas do not originate from benign tumors. Among the factors known to induce sarcoma growth are: genetic defects, exposure to pesticides and herbicides, exposure to ionizing radiation and immunosuppression. Treatment of sarcomas is based on complete tumor resection with a safety margin. Early and correct diagnosis greatly increases the therapeutic options and improves the prognosis.

Citation

Nowicki M, Garbacewicz Ł, Polcyn A, Drogoszewska B. Diagnostic challenges of maxillofacial sarcomas – literature review and case reports. Eur J Transl Clin Med. 2021;4(2):94-100Introduction

Vast majority (about 80%) of all tumors in the maxillofacial region of adults consists of planoepithelial cell carcinoma of medium and high grade. Other malignancies of this region are: adenocarcinomas, cystadenocarcinoma, muco-epidermal carcinoma, osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, lymphomas and myelomas [1]. Furthermore, metastases from tumors of the kidney, testicle, breast, bronchi and lungs can also be found in the maxillofacial region [1-2]. Tumors growing in the oral cavity and facial region may have non-specific signs and symptoms which sometimes leads to wrong diagnoses and wrong treatment.

Material and methods

We conducted a narrative type of review of the available literature published in the English language. Using the keywords "sarcoma", "maxillofacial", "rhabdomyosarcoma", "Ewing sarcoma", "etiology", "histopathology", "treatment", "presentation", "radiology" we searched the Scopus, Google Scholar and PubMed databases. The exclusion criteria were: animal studies, publishing date before 1980. We also screened the references of each included article for any additional relevant articles. No statistical analysis was performed. In addition, to illustrate the diagnostic challenges of sarcomas, we included brief case reports of 2 patients referred to the Orofacial Surgery Clinic of the University Clinical Centre in Gdańsk (Poland) from outpatient dental clinics in the years 2019-2021.

Results

Our search retrieved a total of 92 abstracts, of which 76 were included in further analysis. A total of 42 full-text articles were included in the review.

Case 1

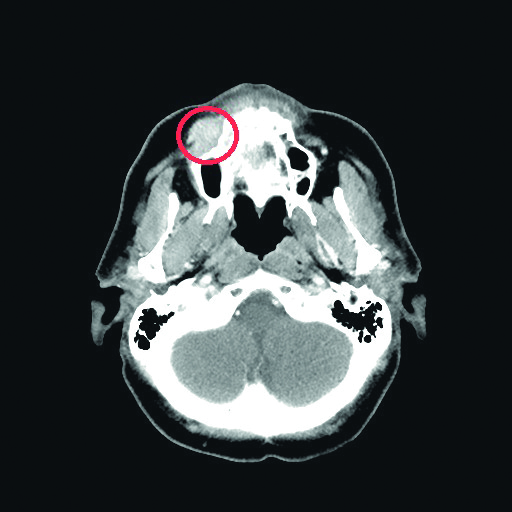

A 57-year old female with history of allergy to analgesics was referred to our Outpatient Clinic in January 2019 due to right maxilla oral cavity vestible shallowing. The patient reported pain radiating to the ear and cranium that began 1 month after she noticed the tumor. Her dentist diagnosed her with edema due to allergy and did not initiate any treatment. The patient’s history was also positive for sensory deficits in the region innervated by the maxillary branch of the right trigeminal nerve, whereas physical examination revealed facial asymmetry due to the tumor of the right cheek. Skin above the tumor was normal. Oral cavity examination revealed shallowing of oral cavity vestible and mobility of teeth 12-17. Mucosa covering the tumor was normal. The volumetric computer tommography (CT) scan of the maxillofacial region revealed a pathological infiltration of the right cheek, adhering to the alveolar process of the maxilla, 26 x 15 mm in cross-section and a segmental cavity of the cortical layer of the alveolar process of the maxilla at the level of the infiltration.

The tumor was biopsied under anesthesia. Histopathological examination revealed small round blue cell tumor with the following immunophenotype: CK AE1/AE3 -, LCA -, TTF-1 -, Melan A -, SOX10 -, p40 -, INI1 +, FLI1 -, CD99 -, PAS -, chromogranin A focally +, synaptophysin focally +, desmin +, Myf4 +, Myod1 +. The clinical picture and the above-described additional tests suggested the diagnosis of rhabdomyosarcoma. In addition, this patient was diagnosed with metastases to the thoracic and lumbar segments of the vertebral column with soft-tissue infiltration. She was treated with radiotherapy of the maxillary sinus region and regional lymph nodes, paliative chemotherapy and paliative radiotherapy of the thoracic and lumbar vertebrae.

Fig. 1. Patient 1’s computer tommography scan revealed a tumor of her maxilla

Case 2

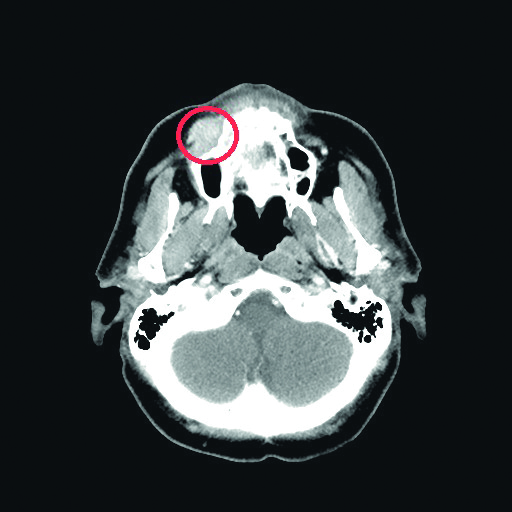

An 81-year old female with history of Alzheimer’s deasease, hepatosplenomegaly and hearing loss was referred to our Outpatient Clinic due to the suspicion of persistent inflammation of the left maxilla. Prior to that she was unsuccessfully treated at an outpatient dental clinic where she was diagnosed with abscess of the left cheek. Oral cavity examination revealed extensive ulceration of the hard palate, the oral cavity vestibule and the alveolar process of maxilla on the left side. The abnormal tissue was biopsied and the histopathological examination confirmed the diagnosis of Ewing sarcoma with the following immunophenotype: CD99 (+), CKAE1/AE3 (focally +), CK7 (-), CK20 (-), CD3 (-), CD20 (-), p40 (-), synaptophysin (-),chromogranin (-), S100 (-), SOX10 (-), TTF-1 (-), FLI-1 (-), Ki67 (> 80%) and PAS (+). In addition, it was determined that the EWSR1 gene was rearranged. Volumetric CT scan revealed extensive pathological infiltration (53 x 73 x 64mm) of the left side of the maxilla, including the left maxillary sinus, palate (without crossing the midline) and left nasal cavity. The infiltration penetrated the ethmoid bone, left frontal sinus, left sphenoid sinus, left orbit and left pterygopalatine fossa, reaching the cavernous sinus and the superior orbital fissure. Due to the extensiveness of the tumor, the patient was treated with paliative radiotherapy and was transferred to a hospice where she died within 3 months of making the diagnosis.

Fig. 2, 3, 4. Patient 2’s volumetric computer tommography scans revealing tumor infiltrating maxillofacial structures

Discussion

Epidemiology

Sarcomas are diverse group of mesenchymal tumors [3]. They comprise of < 1% of adult malignancies and 15- 20% of pediatric malignancies [3-4]. Maxillofacial sarcomas comprise 5-10% of all sarcoma cases [5-12] and < 1% of all malignant maxillofacial tumors [5, 10, 13-16]. Over 70 subtypes of sarcomas were desribed so far [3, 17]. They can be subdivided into two groups: soft-tissue sarcomas (STS, 80% of cases) and osteo/chondrosarcomas (20%) [15-19]. Both types can occur in the maxillofacial region, as noted in the case reports above.

STS have a tendency to form in the muscle, adipose and nerve tissues, joints, blood vessels and deep layers of the skin [4]. They usually occur in the limbs, most often in the soft tissues of the thigh [17, 20], slightly more frequently in men (1,4:1) and the average age at the time of diagnosis is 59 years of age [17, 20]. Among the tumors of this type are liposarcomas, leiomyosarcomas, rhabdomyosarcomas and fiborsarcomas.

Osteosarcomas are less frequent and usually affect a much younger population (< 20 years of age) [17, 20]. Besides bones, they can occur in cartilage as well [4]. The most frequent tumor from this group, osteosarcoma, occurs significantly more often during puberty than in adulthood [17, 21]. Ewing sarcoma is more common in childhood and puberty, though it can occur also in adulthood [17, 21]. Whereas the most common osteosarcoma subtype among adults, chondrosarcoma, usually occurs in patients 30-60 years of age [17, 21].

Ewing sarcomas occur significantly more often in Caucasian patients [4, 22], whereas STS have a slight predilection for patients of African origin (5.1/100 000 people) compared to Caucasian (4.5/100 000) or Asian (2.8/100 000) [4, 23].

Etiology

Sarcomas usually do not grow from benign tumors but occur de novo [24]. In majority of cases the etiology of sarcomas is not known, however external and internal factors were identified as predisposing to sarcoma development [17]. One of the external factors is exposure to ionizing radiation [3]. Sarcomas induced by radiotherapy of breast, lung, testicular or prostate cancer comprise 0.5-5.5% of all sarcomas [3, 25-26]. In addition, research from Japan suggests increased affinity for sarcomas of bones (mainly osteosarcoma) and STS (leiomyosarcoma in particular) among the survivors of atomic blasts in Hiroshima and Nagasaki [17, 27-28]. Another external factor is exposure to chemicals such as polyvinyl chloride (PVC), dioxins, nonorganic arsenic, copper, nitrotoluene, chlorophenol and anabolic steroids [3]. Increased risk of osteosarcoma has been noted among people working with metals, carpenters, bricklayers/masons and blacksmiths [17, 29]. Exposure to PVC, arsenic and treatment with anabolic steroids are related to the incidence of hepatis angiosarcoma (HAS) [30].

The leading internal risk factors are genetic defects and chronic immunosuppression (e.g. in the course of AIDS or after organ transplantation). Chronic immunosuppression in the course of AIDS is favorable to the development of Kaposi Sarcoma (KS), which is associated with a human herpesvirus 8 (HHV8) infection [3]. Patients who are immunosuppressed after transplantation of internal organs also have an increased incidence of Kaposi Sarcoma, particularly in the regions of the world that are endemic for HHV8 [3, 31-32]. In the pediatric population, a co-infection with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) in the course of AIDS is favorable to leiomyosarcomas [33].

Among the genetic defects predisposing to sarcomas are: Li-Fraumeni syndrome (TP53 gene), retinoblastoma (RB1 gene), von Recklinghausen disease (NF1 gene), familial adenomatous polyposis of the colon (APC gene), gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST), Bloom syndrome, Werner syndrome, Carney-Stratakis syndrome and the Rothmund-Thomson syndrome [17].

Physical examination

Swelling of the adjacent tissues is the main sign of sarcomas [5]. Pain is significantly more common in patients with osteo- or chondrosacocomas [5]. Another sign is redness of the skin, ulceration of oral cavity, paresthesias and in case of maxillofacal sarcomas: mobility of teeth adjacent to the tumor [5].

Imaging

CT and MRI scans of the affected area are the key elements of the diagnostic process. If distant metastases are suspected, then imaging of the thorax, abdomen and pelvis are indicated. Positron emission tomography (PET) or bone scintigraphy are needed sporadically [34]. Sarcomas have a variety of radiological presentations: they can be translucent or opaque [5], without distinct borders or homogenous structure, with cystic components and periosteal reaction [35]. Imaging of osteo- and chondrosarcomas may destruction of bone and frequent infiltration of soft tissues [35]. The sunburst sign is pathognomonic for osteosarcoma [5].

Histopathology

The histopathological examination of sarcomas reveals atypical neoplastic cells (in case of chondrosarcoma they are similar to chondrocytes, whereas in case of osteosarcoma the are osteoid-like) with loss of normal architecture. Additional microscopic features are multiple foci of bleeding and necrosis or in the case of osteosarcomas: foci of calcification and ossification [36]. In majority of cases, to make the diagnosis of sarcoma it is necessary to use immunohistochemical or molecular techniques [5, 37].

Treatment

Surgery is the treatment of choice in sarcomas and tumor resection with margin of > 5 mm in soft tissues and >2 cm in bone [16]. Radiotherapy has its place in adjuvant treatment of STS in case of lack of safe margins or paliative treatment [16]. The role of chemotherapy as induction (pre-operative), adjuvant or paliative treatment is equivocal [34]. It was reported effective in the treatment of long bone osteosarcomas, whereas its effectiveness in maxillo-facial sarcomas is the subject of discussion [18, 38-39].

Compared to sarcomas of other body parts, the maxillo-facial sarcomas have worse prognosis in terms of recurrences and survival, which is partly due to the difficulty in performing complete resection (numerous adjacent structures that are critical to patient’s functioning) [16, 40]. Tumor stage at the time of diagnosis is the most significant prognostic factor of oral cavity neoplasms. Early diagnosis significantly improves the prognosis and therapeutic options [41-42]. Both the patient and the dentist have a role in delaying diagnosis and initiation of treatment. Patients frequently delay consulting with a dentist, hoping that the change in the oral cavity will heal spontaneously. Whereas the dentists do not connect the presenting complaints with a potential neoplasm and prescribe analgesics, antibiotics or perform the previously planned procedures without focusing on diagnosing the problem [41].

Clinical pearls

Every patient of a dental clinic and general practitioner (family doctor) should at each visit undergo examination of the entire oral cavity as well as the temporo-mandibular joints, maxillo-facial soft tissues and palpation of cervical lymph nodes. Diagnostic investigation of any pathological change in the oral cavity should also begin at the dental clinic. Patients with suspected neoplasm of the maxillofacial region should be urgently referred to a specialist in order to verify the tumor using imaging and histopathological investigation.

Conclusions

Dentists and general practitioners (family doctors) treat patients who might have oral cavity sarcomas. In the differential diagnosis of tooth-related inflammation, allergic edema, maxillary sinusitis and benign neoplasm of the oral cavity it is important to always consider the likelihood of malignant tumor. During each patient visit it is worth remembering that neoplastic processes of the oral cavity and maxillofacial region may present with a diverse and non-specific set of symptoms. It is very important to take a detailed history from the patient because this helps to confirm or exclude neoplastic disease. Early diagnosis is the key to successful treatment.

No conflicts of interest to report.

References

| 1. |

Chmielik LP, Frąckiewicz M, Chmielik M. Tumours of the bony face in children the treated at the Paediatric ENT Clinic in Warsaw [in Polish]. Otolaryngol Pol [Internet]. 2008;62(4):403–7. Available from: https://otolaryngologypl.com/resources/html/article/details?id=11087.

|

| 2. |

Osuch-Wójcikiewicz E. Otorynolaryngologia praktyczna. Janczewski G, editor. Via Medica; 2005. 353–357 p.

|

| 3. |

Lahat G, Lazar A, Lev D. Sarcoma Epidemiology and Etiology: Potential Environmental and Genetic Factors. Surg Clin North Am [Internet]. 2008 Jun;88(3):451–81. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0039610908000388.

|

| 4. |

Burningham Z, Hashibe M, Spector L, Schiffman JD. The Epidemiology of Sarcoma. Clin Sarcoma Res [Internet]. 2012 Dec 4;2(1):14. Available from: https://clinicalsarcomaresearch.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/2045-3329-2-14.

|

| 5. |

Gürhan C, Şener E, Bayraktaroğlu S, Doğanavşargil Yakut B, Sezak M. Radiological, Histopathological and Clinical Features of 4 Different Sarcomas of Maxillofacial Region. ARC J Dent Sci [Internet]. 2021;6(1):9–15. Available from: https://arcjournals.org/pdfs/ajds/v6-i1/3.pdf.

|

| 6. |

Ketabchi A, Kalavrezos N, Newman L. Sarcomas of the head and neck: a 10-year retrospective of 25 patients to evaluate treatment modalities, function and survival. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg [Internet]. 2011 Mar;49(2):116–20. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0266435610000860.

|

| 7. |

Yamaguchi S, Nagasawa H, Suzuki T, Fujii E, Iwaki H, Takagi M, et al. Sarcomas of the oral and maxillofacial region: a review of 32 cases in 25 years. Clin Oral Investig [Internet]. 2004 Jun 30;8(2). Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00784-003-0233-4.

|

| 8. |

Yang J, Glatstein E, Rosenberg S, Antman K. Sarcoma of soft tissue. In: DeVita VJ, Helleman S, Rosenburg S, editors. Cancer, principles and practice of oncology. 4th ed. Lippincott, Philadelphia; 1993. p. 1436–508.

|

| 9. |

Tsujimoto M, Aozasa K, Ueda T, Sakurai M, Ishiguro S, Kurata A, et al. Soft tissue sarcomas in Osaka, Japan (1962–1985): review of 290 cases. Jpn J Clin Oncol [Internet]. 1988 Sep;18(3):231–4. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jjco/article/18/3/231/810027/Soft-Tissue-Sarcomas-in-Osaka-Japan-19621985.

|

| 10. |

Figueiredo MTA, Marques LA, Campos-Filho N. Soft-tissue sarcomas of the head and neck in adults and children: Experience at a single institution with a review of literature. Int J Cancer [Internet]. 1988 Feb 15;41(2):198–200. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.2910410206.

|

| 11. |

Torosian MH, Friedrich M, Godbold J, Hajdu SI, Brennan MF. Soft-tissue sarcoma: Initial characteristics and prognostic factors in patients with and without metastatic disease. Semin Surg Oncol [Internet]. 1988 Jan 1;4(1):13–9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/ssu.2980040105.

|

| 12. |

Mandard AM, Petiot JF, Marnay J, Mandard JC, Chasle J, de Ranieri E, et al. Prognostic factors in soft tissue sarcomas. A multivariate analysis of 109 cases. Cancer [Internet]. 1989 Apr 1;63(7):1437–51. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(19890401)63:7%3C1437::AID-CNCR2820630735%3E3.0.CO.

|

| 13. |

Vadillo RM, Contreras SJS, Canales JOG. Prognostic factors in patients with jaw sarcomas. Braz Oral Res [Internet]. 2011 Oct;25(5):421–6. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1806-83242011000500008&lng=en&tlng=en.

|

| 14. |

Gorsky M, Epstein JB. Head and neck and intra-oral soft tissue sarcomas. Oral Oncol [Internet]. 1998;34(4):292–6. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1368837598800109.

|

| 15. |

Kraus DH. Sarcomas of the head and neck. Curr Oncol Rep [Internet]. 2002;4(1):68–75. Available from: https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/s11912-002-0050-y.pdf.

|

| 16. |

Kumar P, Surya V, Urs AB, Augustine J, Mohanty S, Gupta S. Sarcomas of the Oral and Maxillofacial Region: Analysis of 26 Cases with Emphasis on Diagnostic Challenges. Pathol Oncol Res [Internet]. 2019 Apr;25(2):593–601. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s12253-018-0510-9.

|

| 17. |

Hui JYC. Epidemiology and Etiology of Sarcomas. Surg Clin North Am [Internet]. 2016 Oct;96(5):901–14. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0039610916520118.

|

| 18. |

Guthua S, Kamau M, Abinya N. Management of maxillofacial osteosarcomas in Kenya. Ann African Surg [Internet]. 2020 Jan 7;17(1):26–9. Available from: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/aas/article/view/192993.

|

| 19. |

Rapidis AD. Sarcomas of the head and neck in adult patients: current concepts and future perspectives. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther [Internet]. 2008 Aug 10;8(8):1271–97. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1586/14737140.8.8.1271.

|

| 20. |

Howlader N, Noone A, Krapcho M, Garshell J, Miller D, Altekruse S, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2012, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD [Internet]. National Cancer Institute. 2015 [cited 2021 Nov 8]. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/archive/csr/1975_2012/.

|

| 21. |

Soft tissue and visceral sarcomas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol [Internet]. 2014 Sep;25:iii102–12. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0923753419340876.

|

| 22. |

Worch J, Matthay KK, Neuhaus J, Goldsby R, DuBois SG. Ethnic and racial differences in patients with Ewing sarcoma. Cancer [Internet]. 2010 Feb 15;116(4):983–8. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cncr.24865.

|

| 23. |

Surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) program. Stat Database: Incidence - SEER 9 Regs Research Data, Nov 2010 Sub (1973–2008) − Linked To County Attributes - Total U.S., 1969–2009 Counties National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Resear. National Cancer Institute Bethesda, MD; 2010.

|

| 24. |

van Vliet M, Kliffen M, Krestin GP, van Dijke CF. Soft tissue sarcomas at a glance: clinical, histological, and MR imaging features of malignant extremity soft tissue tumors. Eur Radiol [Internet]. 2009 Jun 6;19(6):1499–511. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00330-008-1292-3.

|

| 25. |

Davidson T, Westbury G, Harmer CL. Radiation-induced soft-tissue sarcoma. Br J Surg [Internet]. 1986 Apr 1;73(4):308–9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.1800730420.

|

| 26. |

Huvos AG, Woodard HQ, Cahan WG, Higinbotham NL, Stewart FW, Butler A, et al. Postradiation osteogenic sarcoma of bone and soft tissues. A clinicopathologic study of 66 patients. Cancer [Internet]. 1985 Mar 15;55(6):1244–55. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(19850315)55:6%3C1244::AID-CNCR2820550617%3E3.0.CO.

|

| 27. |

Samartzis D, Nishi N, Hayashi M, Cologne J, Cullings HM, Kodama K, et al. Exposure to Ionizing Radiation and Development of Bone Sarcoma: New Insights Based on Atomic-Bomb Survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. JBJS [Internet]. 2011;93(11):1008–15. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/jbjsjournal/Fulltext/2011/06010/Exposure_to_Ionizing_Radiation_and_Development_of.4.aspx.

|

| 28. |

Samartzis D, Nishi N, Cologne J, Funamoto S, Hayashi M, Kodama K, et al. Ionizing Radiation Exposure and the Development of Soft-Tissue Sarcomas in Atomic-Bomb Survivors. J Bone Jt Surg [Internet]. 2013 Feb 6;95(3):222–9. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/00004623-201302060-00005.

|

| 29. |

Merletti F, Richiardi L, Bertoni F, Ahrens W, Buemi A, Costa-Santos C, et al. Occupational factors and risk of adult bone sarcomas: A multicentric case-control study in Europe. Int J Cancer [Internet]. 2006 Feb 1;118(3):721–7. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ijc.21388.

|

| 30. |

Falk H, Herbert J, Crowley S, Ishak KG, Thomas LB, Popper H, et al. Epidemiology of hepatic angiosarcoma in the United States: 1964-1974. Environ Health Perspect [Internet]. 1981 Oct 1;41:107–13. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.8141107.

|

| 31. |

Paola C, Maria C, Rosalia G, Rosalba R, Francesca C, Decio C, et al. Kaposi’s Sarcoma Associated with Previous Human Herpesvirus 8 Infection in Kidney Transplant Recipients. J Clin Microbiol [Internet]. 2001 Feb 1;39(2):506–8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.39.2.506-508.2001.

|

| 32. |

Sarid R, Pizov G, Rubinger D, Backenroth R, Friedlaender MM, Schwartz F, et al. Detection of Human Herpesvirus-8 DNA in Kidney Allografts Prior to the Development of Kaposi’s Sarcoma. Clin Infect Dis [Internet]. 2001 May 15;32(10):1502–5. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1086/320153.

|

| 33. |

Deyrup AT, Lee VK, Hill CE, Cheuk W, Toh HC, Kesavan S, et al. Epstein-Barr Virus-Associated Smooth Muscle Tumors Are Distinctive Mesenchymal Tumors Reflecting Multiple Infection Events: A Clinicopathologic and Molecular Analysis of 29 Tumors From 19 Patients. Am J Surg Pathol [Internet]. 2006;30(1). Available from: https://journals.lww.com/ajsp/Fulltext/2006/01000/Epstein_Barr_Virus_Associated_Smooth_Muscle_Tumors.11.aspx.

|

| 34. |

Ługowska I, Raciborska A, Kiprian D, Rysz M, Krajewski R, Świtaj T, et al. Recommendations in management of head and neck sarcomas. Oncol Clin Pract [Internet]. 2019 Mar 15;14(6):295–301. Available from: https://journals.viamedica.pl/oncology_in_clinical_practice/article/view/58537.

|

| 35. |

Huang L, Chen X, Li L. Image and pathological features of Ewing’s sarcoma in the oral and maxillofacial region. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2016;41(6):637–43.

|

| 36. |

Szylberg Ł, Kowalewski A, Kowalewska J, Pawlak-Osińska K, Kasperska A, Marszałek A. Chondrosarcoma of the maxilla: a case report and review of current literature. Oncol Clin Pract [Internet]. 2018;14(3):160–3. Available from: https://doi.org/10.5603/OCP.2018.0021.

|

| 37. |

Fernandes R, Nikitakis NG, Pazoki A, Ord RA. Osteogenic Sarcoma of the Jaw: A 10-Year Experience. J Oral Maxillofac Surg [Internet]. 2007;65(7):1286–91. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0278239106019409.

|

| 38. |

Kassir RR, Rassekh CH, Kinsella JB, Segas J, Carrau RL, Hokanson JA. Osteosarcoma of the Head and Neck: Meta-analysis of Nonrandomized Studies. Laryngoscope [Internet]. 1997 Jan 1;107(1):56–61. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/00005537-199701000-00013.

|

| 39. |

Smeele LE, Kostense PJ, Van der Waal I, Snow GB. Effect of chemotherapy on survival of craniofacial osteosarcoma: a systematic review of 201 patients. J Clin Oncol [Internet]. 1997;15(1):363–7. Available from: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.1024.7492&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

|

| 40. |

Stavrakas M, Nixon I, Andi K, Oakley R, Jeannon JP, Lyons A, et al. Head and neck sarcomas: clinical and histopathological presentation, treatment modalities, and outcomes. J Laryngol Otol [Internet]. 2016/08/01. 2016;130(9):850–9. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/article/head-and-neck-sarcomas-clinical-and-histopathological-presentation-treatment-modalities-and-outcomes/230B3147EF962E7BFD39ECB3526AC631.

|

| 41. |

Esmaelbeigi F, Hadji M, Harirchi I, Omranipour R, VAND RM, Zendehdel K. Factors affecting professional delay in diagnosis and treatment of oral cancer in Iran. Arch Iran Med [Internet]. 2014;7(4):253–7. Available from: https://www.sid.ir/en/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?ID=364466.

|

| 42. |

Rutkowska M, Hnitecka S, Nahajowski M, Dominiak M, Gerber H. Oral cancer: The first symptoms and reasons for delaying correct diagnosis and appropriate treatment. Adv Clin Exp Med [Internet]. 2020 Jun 29;29(6):735–43. Available from: http://www.advances.umed.wroc.pl/pdf/2020/29/6/735.pdf.

|